Too bad, it's Utopia!

If we have arrived at what Aldous Huxley called ‘the ultimate revolution’, we have done so without many further alerts from the writers who followed his and George Orwell’s attempts to warn us.

In 1993, I wrote a play, Long Black Coat, which could be described as an exploration of the apocalypse of fatherlessness. At the time, I was myself childless, but over the proximate years had been encountering or receiving fragmentary signals concerning a syndrome almost nobody was publicly talking about: the abuse of fathers in family law courts by judges implementing either an outmoded concept of childrearing, or feminist prejudice, or both.

The core of the play was symbolically apocalyptic. I based the central metaphor on a childhood memory of a pamphlet that had been issued to every Irish house during my childhood, at the height of the Cold War, which every householder was supposed to have read and studied: a Civil Defence instruction manual describing the correct response to a nuclear attack. To minimise the risk of damage from nuclear fall-out, householders were to fill their wardrobes with earth from the garden and place them in the windows. They were also to stack all their books on the kitchen table and take their families into the literary igloo thus constructed. It was superficially ludicrous, but also for me strangely evocative of something, perhaps of the survivalist vibe in The Swiss Family Robinson, which I loved as a child.

The play unfolded in such a situation, wherein two men — a young man, Jody, and a much older one, his father (‘Old Man’ in the script) — engaged in a running argument as they constructed their bunker, about the reasons why the young man’s young son was not with them at this possibly terminal moment. The young man blamed his father’s generation of men for having soured the groundwater with patriarchal misbehaviour; the old man blamed his son for being weak. Armageddon loomed over a space dominated by a ‘futuristic’ 3-D headset, a kind of skeletal dinosaur head through which the viewer could enter the ‘news’ as though himself a participant. There was some talk of ‘sheltering in place’. A third character came in for the last five minutes, a familiar gobdaw type about the same age as Jody, who revealed that the 'crisis' had been over for days and they hadn't twigged because their headset had stopped functioning.

The weird thing is that, even though this was not stated, I intended the play to be set in 2020. I had not been thinking of the precise year as a crucial factor, being mainly concerned that the play occur in a moment sufficiently distant in time to open possibilities of changes that need not be explained. In seeking approximately to place the date in a plausible future moment, the year 2020 may have wormed its way into my head because of the connotations concerning normative vision, and also the insinuation of establishing a vantage point in the future from which the past — the present of the performance — could be surveyed. I had been hoping, I think, to suggest the possibility of a totally changed mindset in which the origins of independent Ireland had ceased to represent a cultural problem. Although there was no explicit references in the play to a date, by way of a clue the young man was wearing a faded T-shirt with an image of Padraig Pearse and the slogan '1916-2016'. The critics mostly decided this meant it was set in 2016, taking the device as literally as critics invariably take everything, with a couple of critics seeing all kinds of allusions and allegories to nationalist ideas that weren’t there. The point was it was an old, faded t-shirt!

The anticipation of some kind of major world crisis in 2020 was a collateral factor, and not in the least intended to be germane to the play’s meaning. I've always been of a pretty rational mentality, by which I mean that I buy into stuff only if I've experienced it, but I’ve always been alert to the possibility of phenomena I may experienced without understanding them, or even paying them proper attention. Thomas Sheridan, in his book Walpurgis Night, about the occult tendencies of Adolf Hitler, refers to a syndrome of something like accidental prediction as 'intuitive magic' and 'artistic divination'. Sheridan himself used the term ‘new normal’ on page 197 of his 2011 book on psychopathy, Puzzling People: The Labyrinth of the Psychopath. He’s not, he says, a seer, just good at reading the zeitgeist. ‘I must have picked up on the colossal foreshadowing of what’s coming now, blasting back in time,’ I heard him say on one of his YouTube livestreams, back around the middle of 2020.

That’s how I think my 1994 play came to acquire its ‘prophetic’ tendencies. Because it dealt with a subject of profound interest to me — fatherhood (though I was not yet a father) — and because I pursued the emotional potential of this idea to the utmost of my capacity, I somehow acquired the collateral benefit of artistic divination, enabling me to enter a part of my imagination in which the future was already knowable. This syndrome is related to another, in a more general context, whereby if you do something badly or misguidedly with the right intention, the outcome will exceed your hopes and expectations. Call that God’s handiwork, call it the harmony of the Universe; call it what you will. I have found it to be real.

For the recent Winter Conference of the de Nicola Center for Ethics and Culture, ‘We Belong to Each Other’, at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, USA, I was asked to speak on the topic ‘What writers owe their readers’. This essay is the longform version of what I set out to say. You’ll find the video of the actual discussion here.

Writers/artists owe not just to their readers but to their peoples that they reveal to them the deepest truths about reality, based on close scrutiny and immersed experience. Each writer owes his or her people the fruits of the unique subjectivity gifted them in reality, the perspective that is theirs alone.

There is within artistic/literary circles — and for some reasons acutely in Irish ones — a clinging to the idea of art and literature as removed from reality: art for art’s sake, too lofty and precious to get down and grubby in the real world. But all artists, all writers, have worldviews, and those who pretend not to are perhaps the most dangerous because they support the status quo with a stolidity that, while determinedly reactionary, preserves for itself a form of plausible deniability that is almost impossible for the untrained observer to penetrate.

The current generations of writers have mostly failed to meet this duty, and so have failed their people. Why? Because they failed to tell the truth about reality. And this because they have ceased to extricate themselves from the semblance we mistake for reality and see that it is no longer real, but something constructed around each human person to imprison him in lies.

The proofs are in, in the knowledge, now undeniable, that the world has lately taken a sharp turn that almost no significant writer of the past half-century — in virtually any medium — conveyed more than a flashing glimpse of in advance.

We take breath at a moment when, if one were a certain kind of writer — indeed possibly any kind of writer — it might be necessary to ask oneself some pretty tough questions. Like: how relevant is your work? I don’t mean, ‘How relevant has it been?’; or, ‘How relevant has it appeared?’ — these questions perhaps now fatefully amounting to the same thing. I mean, ‘How relevant is it now — and not just to this moment, but from this moment onwards?’ How relevant is it in the longer run? Is it work that, in 20 years, people will look to and declare to have been prophetic, work that summoned up the age just past, and possibly continuing? Does its trajectory in the years to this moment carry the trace of a journey to where we have arrived, and where we appear to be going?

How many writers, if we dig behind the surface elegance of their words, have grappled with or touched upon things like: the ominous uncontrolled march of technology; the associated neo-colonialism of Big Tech and Big Pharma; the failure of society to keep step with these drifts in the inside lane of ethical growth; the abandonment by the left of its traditional base among the Able classes; the growing disrespect of elites for democratic principles; the sly machinations of the Bilderbergers and Trilateralists; the early signs of Cultural Marxism from the first twitches of third-wave feminism, LGBT agitation and the growth of the race industry; the obsessive preoccupation with sexuality and sexual alternativism; the relentless attacks on the family in culture and via family law intrusion into the most intimate relationships; the general descent into hedonism; the cultural context of growing anxiety; the death of God as a serious subject; the seemingly calculated deracination of the world’s predominant civilisation; the limitless creation ex nihilo of spurious wealth; the exploitation of green scaremongering to oppress and subjugate; the moral inversion at the heart of culture, whereby bad is good and good bad, lies truth and truth lies; the inexorable corruption of the press and academia; the osmotic encroachment of the surveillance state; the collapse of constitutionalism and the rule of law?

If you examine this inexhaustive list with a modicum of attention, it may occur to you that its items have something in common: each signifies or supports an area of exploration that has been rendered taboo in contemporary culture by political correctness, fashion or ideological suggestion. This would seem to suggest that nominally free artists have allowed themselves to be directed in their work by a Muse or Muses that are not exactly the classical inspirational goddesses of knowledge or truth-telling.

These drifts in our culture are mirrored in our literature more in the breach than the chronicling — and also, and not coincidentally, in the disappearance of fiction as an adequate means of anticipating reality, of fiction as what it had been for 300 years: the device by which we humans tried to explain ourselves to ourselves; by which we looked at the world through unfamiliar lenses; by which we collided the rich interior and fraught domestic life of man with the weakening culture of the great outdoors; by which we magnified the crisis and tiny triumphs of the individual self and placed them in the Petri dish of political reality; by which we brought the metaphysical firmament into the manmade hollow blocks of space in which we live.

Have you read a novel in recent times in which a real-seeming human being has entered the world of conspiratorial alliance between Big Tech, Big Pharma and Big Finance to kidnap entire populations and hold them to ransom until they cease to be vulnerable to sickness? Or have you read a book about time slipping into reverse, not exactly literally but in the sense that, as we go forward, the mixed topography of freedom and authoritarianism begin to seem familiar, perhaps from other, older books we’ve read, and the more talk there is about progress and progressiveness, the more the landscape resembles something quite to the contrary?

Was Orwell perhaps right about something else: that all art is propaganda? What is the relationship between writing and history? Is there such a relationship? The world is impoverished by virtue of the fact that there are two reductive ideas as to the answer: one, that literature is not supposed to grub around in the social; the other that writers have a social responsibility.

Writers have no such responsibility, but that does not mean they do not write for their times and their tribes. There is nothing and no one else to write for. Arthur Miller said that all plays were social, by which he meant that plays are for audiences, which are social phenomena. Likewise — although this territory is more complex, — readerships. A readership is an audience, even though its members cannot see each other.

The earliest hieroglyphics placed by homo sapiens on the walls of caves were primarily concerned with two questions: man’s place in the tribe and man’s dreams of transcendence.

In the ancient East — in China and Japan — an artist became such by studying not texts but objects, assimilating their yang and yin, the light and dark of them. In this process s/he was guided by six principles. Every object, every animal, every leaf, has a particular rhythm, and this principle — the rhythm of the thing — was the first and most important. After this came ‘organic form’, which was the outline of the thing or being or entity, which must also carry the rhythm of the thing. After this came ‘trueness to nature’, which means trueness to the rhythm and the form. Then comes colour — the yin and yang, which reveals the movement of the object or being. Next comes ‘the placement of the object in the field’, a remarkable idea: that the object or being can be captured as part of the world. And finally comes ‘style’, which is not what we mean by style but instead the matching of the energy of the execution with the nature and rhythm of that which is depicted. These are the Taoist principles for depicting reality. All art and all writing, all stories — true, mythological, or merely fictional — must be written in accordance with something akin to these principles. And in this list we can see a constant through line of connection with the idea of discovering the world as it actually is, in its essences and discoverability. From this we gain a more precise sense of the function of the artist: he is a craftsman in revealing the world. And the same goes for words — for literature, fiction, reportage, even journalism when it is good, or — better — when it is great.

The first needs a child experiences are the needs for food and love. After that, a close third, comes the need for story. If you watch a young child playing on a rug with new toys — shifting his building blocks with tractors and excavators — you notice that he treats everything as if it were self-evidently mysterious. He looks at things carefully, touches them, smells them, licks them. He seems to be simply going through motions that babies do for no reason, but really he is constructing a version of the world from the only available evidence, using the only instruments available to him: his five senses. This is how each of us constructed the world to begin with, though we imagine we did so in a process we grandly call ‘education’. In fact, education came afterwards, and not necessarily to improve what had already occurred. Really, to continue building a coherent and reliable version of the world, we need to approach things like the child — entering into everything using as many of our senses as possible. Books have their place, but if they come too soon and are treated with such gravity that they displace the world, books of any kind result in a dissociated abstractness.

Most writing that we call ‘literary’ in our cultures no longer conforms to the ancient Eastern ideas of rhythm etc., but simply engages much in the manner of a literary Olympics with the pantheon of past writing and present champions. The result is that novelists, short storytellers, dramatists etc, write into what you might call the ‘literary cloud’, contributing their tithe to the archive of aesthetic abstraction about nothing but itself.

Who can we credit with following up on George Orwell’s 1937 prediction (The Road to Wigan Pier) that the vision of the totalitarian state would be substituted by the vision of the totalitarian world? And where to be found is the modern Faustian tale called, maybe, Everything You Know is Wrong, in which a rock star who rises from nowhere with a music that praises God and decries the corporate turn being taken by the world, ends up taking tea with the architects of the New World Order. Or what about a novel called The Useless Eaters, about people who decide to eat the rich before the rich eat them? I am not talking about sociology, about instrument literature dedicated to social inspiration, but rather asking a question: If writers can write about human beings in the world without touching on what is already gestating under their feet, how ‘truthful’ can their books be? The point is not to demand a sociological literature. It is to ask: How can the inhabitants of an era’s literature remain impervious to the unprecedented events in the world outside their make-believe windows?

Throughout the history of the novel, stories were placed in something passing for the reality of the past, present or future. What we see is that our writers have mostly written about a different world to the one now culminating in front of our eyes. They write, sure, about manners, and character, and mystery of a sort, but they leave most of what humankind in the Westerns hemisphere has been experiencing untouched, and as a result have assisted many in not understanding what they were experiencing. Why? Because they did not notice what was happening? Hardly. Because, unbeknownst to themselves, they had fallen prey to ideological spells cast by those who wished to steal the world from under its people’s feet.

So what really is a novelist? Is he or she a voice of truth from within the culture or a voice of misinformation and manipulation, part of the bread and circuses routine that keeps people singing in their chains, exposing them to risks, deluding them with ideals of freedom and promises of peace and truth? It’s a good question. The answer may not be what you used to think it was.

And the same is true of theatre. Modern theatre seems to mimic television or construct a determined anti-art, which is to say an art based on pastiche or parody of what came before it. The artists, writers, are really just parasites, caricaturists, satirists, forgers. At a glance we can tell such anti-art from the real thing: It is not truthful. It always seems to be about other people. Its practitioners are distracted from their vocations by ideology, fashion and the prospect of easier success.

In, say, a decade’s time, when we may find ourselves — if present trends are not curtailed — in a neo-feudal dystopia; enslaved by technology and medical tyrants; paralysed finally back into a silence akin to that which preceded the first human cry; crammed into hive cities that are far smarter than we; our lives and thoughts an open book for self-appointed big siblings to peruse; with nothing to our names but the clothes we creep around in — will we hear the name of any writer of today — say, February 3rd 2021 — and think: He/she called it years ago? It’s all there in those books!

Shamefully, we have to go back a human lifetime, to the middle of the last century, to find writers whose work can realistically be deemed prophetic of the present moment.

First there was Huxley; then Orwell; then. . . Who?

Michel Houellebecq, maybe. Certainly he has caught the degradation, the degeneracy of the West; the craving for servitude to the basest passions; the longing for capitulation to a Master or Mistress. He has prophesied and denounced and warned. That much is certainly true.

He tackles great themes of our time — the rise of Islam, transhumanism, sexual consumerism, cloning, post-Sixties hedonism — and always as a backdrop to his study of the movement of human beings in time and space. To read his books is to feel you are engaged in some vital exercise in understanding the age in which you live. His theme is no littler than the decline and fall of European civilisation.

Fifteen months ago, in an article about Houellebecq for First Things: I wrote the following:

‘Houellebecq writes about the disappointment, sadness, loneliness, anguish, terror, boredom, despair imposed by a culture unfit for human habitation. He exposes the freedom con pedalled since the Sixties and defended in the name of what is called progress. He summons up a diseased world, leaving the reader repelled and unsettled, but also relieved that at last the truth is told. He does not raise false hopes, but presents his characters in extremis within the collapsing culture, their humanity no longer capable of extending into the available space. But all the while there is an implicit comparison of an unexpected kind: that something better is possible; something that may once have existed, perhaps a memory deep in the recesses of the reader’s mind.

And I also write the following paragraph, which is not specifically about Houellebecq, but about the moment he writes in:

‘Almost everybody seems to feel we are heading for some cliff edge. We may not agree what we mean by that, but we sense a catastrophe of some kind — existential, ecological, demographic or arising from some uncertain bellicosity — is just around the corner after next. And we sense that, when it comes, this catastrophe will have the mien of a wilful self-destruction. Such dreads growingly invade the minds of Europeans, rendering them the allies of their own gravediggers. The defining characteristic of the present age might be deemed the desire to subvert and destroy the institutions, traditions and beliefs that converged to become what is called Western civilisation. This iconoclasm is carried out in the name of freedom — sexual freedom, chiefly — but accompanied by an unconscious relinquishing of the life-force. The great mass of Western humanity seems easy with abandoning the ideas that constituted the heart of its civilisation from the beginning.’

As prophecies go, that’s not half bad.

Houellebecq is, in a sense, of a different culture. He is a Frenchman, writing in French. He lived in Ireland for a while, for tax reasons no less, but we scarcely noticed. He is not of the Anglophone world, which may count in this context because he is that much more removed from the ideologies that have saturated Western civilisation, mostly via the English language.

He is also, in a certain sense, more a reporter than an artist. For his 2011 book, The Map and the Territory, he created a character called Michel Houellebecq, a writer. The book’s ‘hero’, Jed, a painter, visits the famous novelist to present a portrait he’s painted of him. As Houellebecq prepares a meal, Jed examines the bookshelves and is ‘surprised by the small number of novels — classics essentially. However, there was an astonishing number of books by social reformers of the nineteenth century: the best known, like Marx, Proudhon, Owen, Carlyle, as well as others whose names meant nothing to him.’

In my First Things essay, I described him thusly:

‘Houellebecq does not read as a natural or even comfortable novelist, but someone who has invaded an increasingly redundant form to say things incapable of being heard otherwise. He does not write recreational yarns, nor book-shaped sedatives to escape into. A kind of investigative reporter who reports truths rather than facts, he is a red-pilled Hunter S. Thompson in reverse gear, the chief scribe of the counter-counterculture, the Great Gonzo of Truth-telling, the one prepared to go further in describing the depths of degradation and hopelessness to which libertinism and nihilism have dragged us. His books are documents of an internal forensics of human decline that happen to take — mostly, anyway — the form of stories.’

Is there, writing in the English language in the 21st year of the 21st century, any writer of fiction who might be said to have drilled into the dense reality of the three or four decades leading to the present and set down in story our path to this moment? What might the canon of such a writer look like? Well, it might contain many of the elements that Houellebecq has chalked his line around: the corpses of our cultural inheritance sprawled dead in the mud. I cannot come up with such a novelist’s name, though my reading may not be exhaustive.

To find writers in that period who have been genuinely prophetic, it seems to me we must look to reporters — journalists, albeit a very few and of a very particular kind, and foremost of all the most maligned and derided, David Icke, the so-called arch-conspiracist, who is classically defined by his indifference to fashion, ideology of political correctness.

Looking further afield, we may pause at the work of sci-fi writers, from whose ranks I would pluck the name of Philip K. Dick.

In Dick’s The World Jones Made (I956), the action of the novel takes place in a hyper-state created on the ashes of the globe scorched by the third apocalypse. The book was written decades before the present system of mind enslavement called ‘political correctness’ emerged. The system of rule in the society described in the book is dictatorship; the official ideology is ‘Relativism’. Uttering categorical statements is against the law. In 2021 Ireland, we’re rounding the final corner to such a society, having gone from 0 to 10,000 kph in about a month of wet Sundays.

Dick’s 1964 novel The Penultimate Truth is set in a future where most of humanity lives in large underground shelters. The world is subject to an information monopoly. The people are told that World War III is being fought overhead, when in reality the war ended years ago. Those who have a different point of view than the Combine are not allowed to speak or are silenced if they try to. This book present a study of how a society can be managed with the help of a fictional, or exaggerated sense of danger. The population lives in a state of panic constantly fuelled by media. Sound familiar?

In Ubik (1969), the main characters do not realise that the world they live in is a prison. Most of characters in the story are all but dead but do not know it. Their reality is slowly but systematically disintegrating, as they gradually become a prey to a sinister existence that sucks the remnants of their spiritual energy. Hello? Anybody there?

Dick wrote of extra-terrestrial colonies, and now we have Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos planning what they’re going to do with those of our children they’ve already decided have no place among their exalted offspring and descendants.

Is this not prophecy? Perhaps snobbery concerning genre and form have prevented us from paying attention to writers like this.

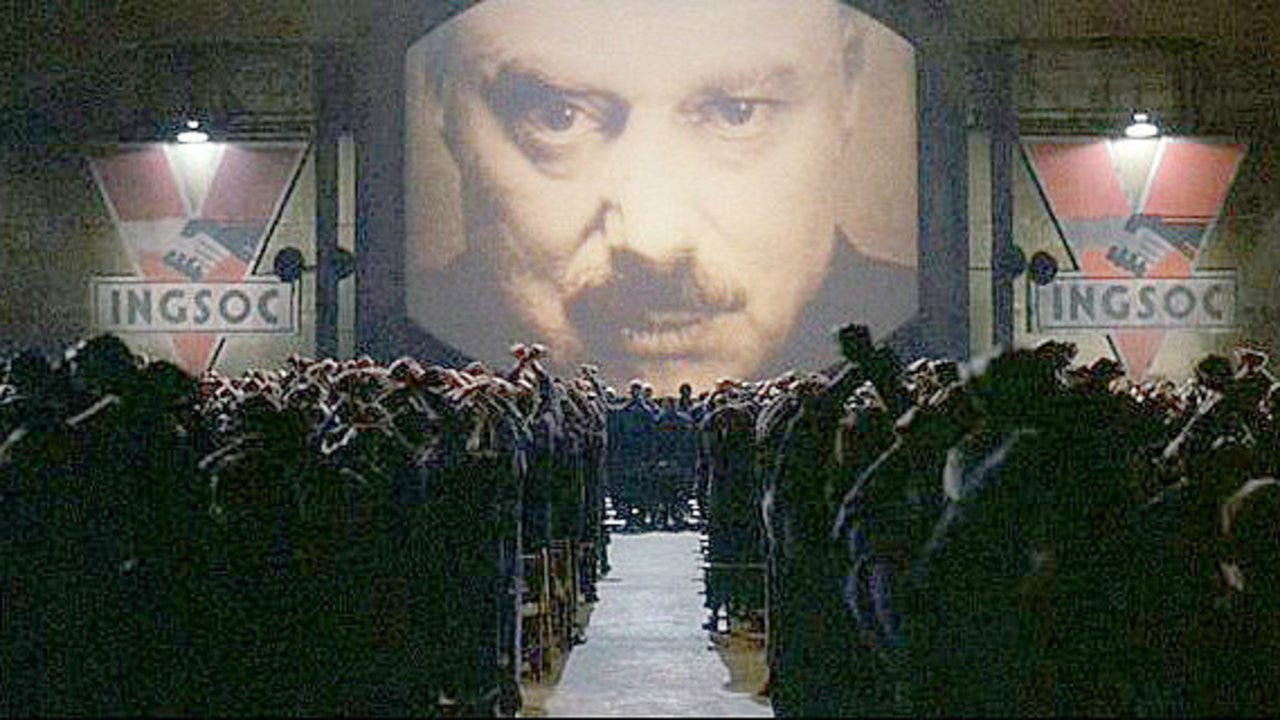

We reach, then, for Huxley and Orwell, all but clichés of the dystopian genre — precisely because the genre was abandoned by mainstream writers around the midway point of the last century.

There are also those who remain convinced both Orwell and Huxley were privy to insiders of the Establishment and not prophets, and thus were relaying factual information rather than imaginative visions.

Huxley certainly had an inside track on the future, being the younger brother of Julian Huxley, an evolutionary biologist, and eugenicist, and the first Director General of UNESCO — the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organisation. UNESCO, according to some of its critics, is an internationalist body masquerading as a instrument for peace and unity, when its real intention is the fomenting of an international collective communism, the dominance of science and the introducing throughout the world of ‘common core’ education, so as to indoctrinate the young with an impoverished education. We can imagine that Julian Huxley might have occasionally brought some of his work home with him. In some of his own writings he essentially sets out the whole scenario of Brave New Worldwith a straight, matter-of-fact face. Orwell was different. There is nothing in his background suggesting a similar inside track. In truth, though, Orwell developed his predictions from his close observation of history, whereas Huxley was privy second-hand to the plans of the Combine, and was therefore more a reporter like David Icke, albeit with the deniability of fiction. Orwell wrote 1984 more or less on his deathbed — an amazing feat of human endurance in which he was as though driven by visions. He wasn't a believer — not a literal one anyway — but he had a finely tuned ethical perspective and a fundamental belief in the notion of the dignity of every human being. He got things slightly 'wronger’ than Huxley but not, I mournfully observe, the essence of the future we're now facing.

There is another reason why it is a mistake to read Huxley’s book as science fiction. His objective is not to speculate, still less to create a fantasy world that might or might not resonate with reality as it unfolds. What he wrote about, fundamentally, was the disjunction between man’s creative ingenuity with scientific systems and technologies and his capacity for moral growth.

Fourteen years on from its first publication, he wrote a new Foreword for the 1946 reprint of Brave New World, in which he explained that his interest was in the effects of science as directed at mankind: ‘The theme of Brave New World is not the advancement of science as such; it is the advancement of science as it affects human individuals. The triumphs of physics, chemistry and engineering are tacitly taken for granted. The only scientific advances to be specifically described [in the novel] are those involving the application to human beings of the results of future research in biology, physiology and psychology. It is only by means of the sciences of life that the quality of life can be radically changed. The sciences of matter can be applied in such a way the they will destroy life or make the living of it impossibly complex and uncomfortable; but, unless used as instruments by the biologists and psychologists, they can do nothing to modify the natural forms and expressions of life itself.’

In this Foreword, he firstly explained why he had decided against updating his book, originally written to project its characters six centuries into the future. Asserting that the defects of the book were considerable, he had decided against rewriting, since ‘in the process of rewriting, as an older, other person, I should probably get rid not only of some of the faults of the story, but also of such merits as it originally possessed. And so, resisting the temptation to wallow in artistic remorse, I prefer to leave both well and ill alone and to think about something else.’

He did, however, describe what he thought the greatest defect of the story: that his character, the Savage, had been sold short by being offered just two alternatives: insanity in Utopia or a primitive life in an Indian village, a life ‘hardly less queer and abnormal’. Now, he declared himself no longer keen to demonstrate ‘that sanity is impossible’. If he were to rewrite the book, he revealed, he would offer the Savage a third alternative: he would not be transported to Utopia before having an opportunity to learn at first hand about the nature of a society composed of freely co-operating individuals devoted to the pursuit of sanity. Already, in other words, he was thinking of putting in place not just a warning about the future but a possible way of avoiding what seemed inevitable. The people governing the brave new world, though not exactly sane, were not madmen either, he insisted. Their aim was not anarchy but social stability. If the tyrants could be given what they wanted by lesser means, he postulated, they would probably go for it. ‘It is in order to achieve stability that they carry out, by scientific means, the ultimate, personal, really revolutionary revolution.’

The ‘really revolutionary revolution’, he wrote, needed to occur ‘in the souls and flesh’ of human beings.

Remember, he wrote Brave New World between the wars, a time of dissolution and rising insanity. Revising the book after WWII, he placed sanity as his highest value. His comments are largely particular to that moment, touching on war, atomic energy, the nuclear threat, Bolshevism, fascism, inflation. There is in truth very little that resonates with the world of the third millennium. Like most seers of the pre-1989 era, he saw nuclear obliteration as the defining threat. The nearest to a general prediction is this: ‘To deal with confusion, power has been centralized and government control increased. It is probable that all the world's governments will be more or less completely totalitarian even before the harnessing of atomic energy; that they will be totalitarian during and after the harnessing seems almost certain. Only a large-scale popular movement toward decentralization and self-help can arrest the present tendency toward statism. At present there is no sign that such a movement will take place.’

There was, he noted, no reason why the new totalitarianism should resemble the old. ‘Government by clubs and firing squads, by artificial famine, mass imprisonment and mass deportation, is not merely inhumane (nobody cares much about that nowadays); it is demonstrably inefficient and in an age of advanced technology, inefficiency is the sin against the Holy Ghost. A really efficient totalitarian state would be one in which the all-powerful executive of political bosses and their army of managers control a population of slaves who do not have to coerced, because they love their servitude. To make them love it is the task assigned, in present-day totalitarian states, to ministries of propaganda, newspaper editors and schoolteachers. But their methods are still crude and unscientific.’

This was also to be his essential response to the 1949 publication of his former pupil, George Orwell’s book, 1984, conveyed to the author precisely three months before Orwell’s death from tuberculosis in January 1950. This episode accentuates a strange incongruity: the two books, 18 years apart, appear to be in the wrong order. One might have expected the boot-in-the-face dystopia story to emerge first, followed some time later by the account of the tyranny-by-pampering. Huxley’s — due to its author having the inside track — came first, by nearly two decades.

In this letter, Huxley used an interesting phrase for what both he and Orwell were anticipating in their respective books: ‘the ultimate revolution’. Incidentally, in 1962, Huxley would deliver a lecture at U.C. Berkeley titled ‘The Ultimate Revolution: Getting People To Love Their Servitude’, in which he defined this process as ‘a method of control by which a people can be made to enjoy a state of affairs by which by any decent standard they ought not to enjoy.’

Having assured Orwell — whom he had taught French at Eton — 'how fine and how profoundly important the book is', Huxley went on to engage is what reads in retrospect like a put-down, an unfavourable contrasting of the book with his own prophetic work of 18 years earlier.

He noted: ‘The first hints of a philosophy of the ultimate revolution — the revolution which lies beyond politics and economics, and which aims at total subversion of the individual's psychology and physiology — are to be found in the Marquis de Sade, who regarded himself as the continuator, the consummator, of Robespierre and Babeuf.

‘The philosophy of the ruling minority in Nineteen Eighty-Four is a sadism which has been carried to its logical conclusion by going beyond sex and denying it.

‘Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful.

‘My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World.

‘I have had occasion recently to look into the history of animal magnetism and hypnotism, and have been greatly struck by the way in which, for a hundred and fifty years, the world has refused to take serious cognizance of the discoveries of Mesmer, Braid, Esdaile, and the rest.’ [All three were among the founding fathers of hypnotism, then known as ‘mesmerism’, which was named after the German doctor Franz Mesmer, who developed the view that animal magnetism was an invisible natural force and could by induced by trance.]

‘Partly because of the prevailing materialism and partly because of prevailing respectability, nineteenth-century philosophers and men of science were not willing to investigate the odder facts of psychology for practical men, such as politicians, soldiers and policemen, to apply in the field of government.

‘Thanks to the voluntary ignorance of our fathers, the advent of the ultimate revolution was delayed for five or six generations.

‘Another lucky accident was Freud's inability to hypnotize successfully and his consequent disparagement of hypnotism.

‘This delayed the general application of hypnotism to psychiatry for at least forty years.

‘But now psycho-analysis is being combined with hypnosis; and hypnosis has been made easy and indefinitely extensible through the use of barbiturates, which induce a hypnoid and suggestible state in even the most recalcitrant subjects.

‘Within the next generation I believe that the world's rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience.

‘In other words, I feel that the nightmare of Nineteen Eighty-Four is destined to modulate into the nightmare of a world having more resemblance to that which I imagined in Brave New World.

‘The change will be brought about as a result of a felt need for increased efficiency.’

Education was the key, he opined in that 1946 Foreword, to the assertion of ultimate control over humanity — refusing to educate, that is. ‘Great is truth, but still greater, from a practical point of view, is silence about truth.’ This, he advised, ought to be accompanied by a more refined sense of ‘the problem of happiness’, of making people love their servitude by imagining it to be contentment.

The love of servitude, he wrote, required firstly economic security, but then, and more importantly, ‘a deep, personal revolution in human minds and bodies.’

The Ultimate Revolution would require, inter alia, much improved techniques of suggestions, starting in the cradle, and the later enhancement of these by drugs — ‘something at once less harmful and more pleasure-giving than gin or heroin’, and ‘a fully developed science of human differences, enabling government managers to assign any given individual to his or her proper place in the social and economic hierarchy’. And finally, as a ‘long-term project’, the development of ‘a foolproof system of eugenics, designed to standardize the human product and so to facilitate the task of the managers’. He guessed that the real equivalents of soma, hypnopaedia and a scientific caste system were by then ‘probably not more than three or four generations away.’ He thought the sexual promiscuity of Brave New World, judging by American divorces being already on a par with marriages, was within reach. ‘In a few years, no doubt, marriage licenses will be sold like dog licenses, good for a period of twelve months, with no law against changing dogs or keeping more than one animal at a time. As political and economic freedom diminishes, sexual freedom tends compensatingly to increase. And the dictator (unless he needs cannon fodder and families with which to colonize empty or conquered territories) will do well to encourage that freedom. In conjunction with the freedom to daydream under the influence of dope and movies and the radio, it will help to reconcile his subjects to the servitude which is their fate.’

‘All things considered it looks as though Utopia were far closer to us than anyone, only fifteen years ago, could have imagined. Then, I projected it six hundred years into the future. Today it seems quite possible that the horror may be upon us within a single century. That is, if we refrain from blowing ourselves to smithereens in the interval.’

He briefly gestured towards the possibility of an alternative course for society: the development of science not as the end of human progress but ‘as the means to producing a race of free individuals.’ Otherwise he saw a choice between an assortment of independent militarised localised totalitarianisms or a single supranational totalitarianism, as the sole means of managing the chaos arising from untrammelled technological progress, finally arriving at ‘the welfare-tyranny of Utopia.’

It is often said that the kind of dystopianism we are talking abut now is more Huxley than Orwell, but I am not sure this is so. Already it feels more like the Orwellian fist in the Huxlean glove. Or perhaps, a Huxlean game of footsie with the Orwellian boots on! To steal a crystal phrase from Jean Baudrillard: ‘Too bad, it’s Utopia!’

In any event, it is clear now that the option of applying science to the project of nurturing a race of free humans has long since been abandoned. The choice, then, by Huxley’s persuasive logic, was always going to between two forms of despotism, and it now clear that the choice has been made: in the future, human beings will live in a supranational monocracy, sustained in a kind of peace by drugs, technology and welfare, with the jackboot laces slightly undone, as though at the end of a hard day’s kicking.

The problem is a human one. It had long been held that it would prove impossible to create a computer that was cleverer than the human being, simply by virtue of the human having been its creator. This now reveals itself as naïve. The combination of algorithm and Big Data has opened up new vistas of possibility, since data can be harvested at several removes from the human to cast variegated new lights on probability patterns in behaviour that allow the Combine to understand us better than we understand ourselves. Moreover, that optimistic hypothesis concerning the continuing mastery of man presumed that all men would remain in control of their destinies, and overlooked that another way of making machines more intelligent would be to make the average human more stupid.

Much of this escalating stupidity has been engineered by cultural reprogramming. Tradition, Julian Huxley once observed, is the way in which the process of evolution has been transmitted for centuries; but, because we have started to suspect tradition, deny its value, interfere with it, abolish it, we have succeeded in stalling the evolutionary process even as the technologies we have created out of the momentum of our past evolving accelerate and pass us by. Evolution, hitherto the carrier of the impulse of human progress, has gone into reverse, while, going by the observed evidence of the technologies, we think of it as still accelerating forward. We pass our own ghosts on the way back into history.

Progress, therefore, is just another conditioned delusion. Genes mutate in accordance with environmental needs and stresses; the less challenges, the more obsolescence. The evidence seems to be telling us that, as our world becomes more technologised, we human beings have less reason to make use of our wits, which as a consequence are deserting us. This may be part of the explanation for how accurately the responses of 2020 have confirmed the hypotheses outlined by both Huxley and Orwell: Most of us dearly love Big Brother.

And perhaps a deeper factor is the neglect of the natural transcendent appetites of the human imagination — as a result of years of the promotion of a pseudo-rationalism that ignored most of the most fundamental human questions, majoring in the denigration of religion.

The chief takeaway from the Covid cult to date is that, spiritually we are mostly dead people — we just have not noticed it yet. The world we inherited is steadily falling apart around us. But we are too ‘sophisticated’ to recognise the signs, too certain of the ideas we have been taught, too proud to notice that we are unable to save ourselves by means of our efforts alone.

For societies, as for human person, the religious dimension is a question of imagination. Or, perhaps, the capacity to fully imagine reality becomes a religious question: Imagination needs to be bedded down in a sacred, transcendent, eternal order. The defining characteristic of the present age might be diagnosed as the desire to subvert and destroy the institutions, traditions and beliefs that converged to become what is called Western civilisation. This iconoclasm is carried out in the name of freedom — actually, of sexual freedom purely — but is propelled by a great error: the assumption that any properties of this inheritance that were essential to the functionality and cohesion of the society and its human quotient would, if capable of having a continuing usefulness, be both amenable to rationality and comprehensible as a matter of discernible utility. Our problem, in short, was that we ceased to understand that the transcendent implied not a knowledge of a different way of thinking, which was out of our reach, but an essential acceptance that such a different way of thinking existed.

Put simply in this context, the inheritance of Christianity can be rinsed down to the idea that human happiness is better achieved by the sublimation of superficial desiring in the visualisation of a transcendent order of being. A functional culture in this sense requires a foundational mythology that enables it to transcend what might be called a state of continuous present time. This mythology relates to the past and to the putatively eternal future, and functions to render the present subservient to things higher and greater than itself. The nature of the rupture that has opened up in modern society has the to do with the repudiation of this idea in favour of something that amounts to a culture rooted in itself and its own selectively identified and apprehended origins. This can seem, for a time, highly functional, exhibiting signs of a previously undreamt-of freedom and openness. But it is a chimera, a fake, because it has no roots and no ultimate objectives that can either be formulated or achieved. Only a culture rooted in the sacred is capable of sustaining a human person or society over the long run.

It is true that such a pseudo-culture can achieve the semblance of functionalism by mimicking the idea of a transcendent culture, since it maintains the outward appearance of a quasi-eternal perspective on reality, but this is actually an illusion, and all of the available artefacts (what they are, really: anti-art) will reveal themselves as tautologies. A novel, for example, will not take its reader on a journey taking off into the infinite, but will return him to an enhancement of the emblematic shocks and/or sentimentalisms that identify the work as itself. It is possible to prolong the life of this pseudo-culture by the practice of parasitism on that which it denies. A painting may parody the rejected inheritance, and yet derive its only life from what it derides and blasphemes. Really, the roots of this pseudo-culture are as functional as those of a poppy in a dusty corner, causing it to flare momentarily and then die for want of sustenance. But such a pseudo-culture is incapable of formulating any enduring idea of the beautiful, the good or the true, because it has no eternal measure: man and his desire for immediate freedoms has become the measure of all things. Yet, this freedom becomes increasingly impossible, since the untrammelled pursuit of the literal desiring of each and every human will in a short time lead to chaos, followed by outright destruction of everything, followed hard by tyranny.

Welcome to the brave new world. Too bad — it’s Utopia. But not as we imagined it. Outside, it's 1984!