This is China

An abridged version of this article, about the Chinese concept of ‘social credit’, soon to become the new norm in the ‘new normal’ of Western societies, was published by First Things in October 2019.

My daughter, who is 23, recently passed her driving test (first time too!). She had the usual difficulties young people in Ireland have with getting insurance. After being quoted some astronomical premiums, she eventually did business with a company that puts an electronic spy in her car and gives her credits for safe driving, which can be used to reduce her premium next year. What it rinses down to is that the insurance company has access to a constant thread of data about her driving, for example obedience to speed limits, safe stops and so forth, criteria based on the company’s analytics of the relationship of driver behaviour to previous insurance claims. She gets regular updates via text on how her driving is shaping up.

On its face, this seems like an ingenious solution to a contemporary problem: high insurance premiums arising from the escalating risk of accidents involving inexperienced drivers. My daughter is happy to be able to get relatively inexpensive insurance. As a father, who has had to sign off on riding shotgun, I am moderately happy that she is being monitored and corrected while I sleep.

But, I can’t help thinking that another frontier has been breached on the way to a new kind of unfreedom. We have been on this road for some time, but gradually the landscape around us is changing, becoming more austere and forbidding. If you had announced two decades ago that people would be prepared to allow a device into their homes that could monitor their most intimate domestic moments, we would have laughed long and loudly. If you had suggested that people might be prepared to exchange for the ability to gossip and chit-chat the most detailed descriptions of their daily habits, movements, spending and consumption patterns, incomes, and other essential information such as humans once guarded with a fierce discretion, we would have declared it impossible.

We would have been wrong. All of this has been surrendered with barely a shrug.

We are already moving into what seems to be the destination stage: the creating of a new form of governance operating on the basis of a panopticon, using data and algorithms, rewards and punishments, to impose control on societies. This, on the basis of an ongoing Chinese experiment, to be called ‘social credit’, which shifts the weight of cost and responsibility of policing on to the citizen, who becomes the self-policed. If these systems can be made to work, the citizens will in the future largely police themselves and each other.

The development speaks of the demise both of the state and of the nation, and the concomitant rise of a new model of government involving transnational public/private collaborations. We already have these in Ireland, and so can see, to some extent, where this might be leading: our mediocre politicians hand-in-glove with Google and Facebook to impose censorship and punish those who dissent on jointly–agreed policies like gay marriage and open borders. The very idea, in combination with what we have already observed about public acquiescence in quite extraordinary intrusion of Big Tech into the lives of humanity, edges us closer to the probability of a one world government based on intimate surveillance administered by Big Data.

We are already halfway there: insurance rebate offers, loyalty cards, cookies, have all broken the ice of our potential resistance. We already have digital profiling courtesy of Facebook and Google. We have too much to lose in easy comforts to look to the big picture that will become clear only with time. In the world run by social credit, an individual’s score becomes the ultimate truth of who that person is, determining whether he can borrow money, get her children into the best schools or travel abroad; whether you get a room in a particular hotel or a table in a particular restaurant.

China has already embarked on constructing a special credit system which had been intended to be fully operational next year [2020] but is now unlikely to be ready to meet that deadline. The scheme, which will be mandatory, is being piloted by city councils and tech companies, using face-recognition and other monitoring technologies to harvest data. When fully operational, it will be centralised and government-controlled. Citizens will face constant monitoring and, under stipulated headings, will lose points from their ‘personal scores’ for infractions such as ‘spreading fake news’, late payment of bills, refusal of military service, defaulting on a loan, running a red light, using public transport without a ticket, watching too many video games, tax evasion, walking a dog without a leash, local protectionism, overcharging, academic impropriety, offering or accepting commercial bribes, wasting money on frivolous pursuits or purchases, making fraudulent claims for compensation, loitering in public places or smoking in designated no-smoking zones. Punishments will include travel and holidaying restrictions, denial of Internet services, barring from state employment, refusal of higher education to offender or offender’s children, confiscation of pets or motor vehicles, and so forth. If you’re a ‘bad citizen’, you will drag down the scores of those around you, including your loved ones. If you say something bad about the government on social media, this may affect your family and colleagues and their families. This, in turn, inculcates a powerful form of peer pressure as well as a fear of ostracisation. People with good scores will receive bonuses such as hotel and travel upgrades, speeded-up travel permissions, et cetera.

The Chinese pilot is directed initially at economic, commercial and financial aspects, a nationwide scheme for tracking the trustworthiness of citizens, corporations, and government officials. The goal is the development of a national system for monitoring the ‘character’ of citizens and companies. The Chinese government is determined to ‘[f]orcefully launch activities to let universal education and propaganda about credit enter enterprises, enter classrooms, enter communities, enter villages and enter households.’ The government expresses its objectives as the nurturing of ‘sincerity and trust-keeping’ so that these become conscious pursuits of the entire society. ‘Sincerity’ translates roughly as integrity. The government also ominously pledges to ‘[r]ealistically implement rewards for reporting individuals, and protect the lawful rights and interests of reporting individuals.’ According to a document issued by the Chinese government, the purpose of social credit is to ‘commend sincerity and punish insincerity’. The ‘inherent requirements’ of social credit systems are concerned with ‘establishing the idea of a sincerity culture’, and, carrying forward ‘sincerity and traditional virtues,’ its objective is ‘raising the honest mentality and credit levels of the entire society.’

China already has nationwide blacklisting programmes — ‘black lists’ (the offenders) and ‘red lists’ (the compliant) used to identify and punish those breaking commercial and industrial regulations. Some local authorities have solicited help from social media platforms to orchestrate public shaming of people on such black lists, and some social media companies are co-operating with the authorities by publishing mugshots of defaulters.

Larry Catá Backer of Penn State University published a paper titled Next Generation Law: Data Driven Governance and Accountability Based Regulatory Systems in the West, and Social Credit Regimes in China, in which he explores the possibilities of social credit systems being introduced and working in Western societies.

He looks in some detail at the Chinese social credit system and the ways in which a Western version might imitate or vary from this. Already, he claims, there is a ‘quite visible move toward social credit in the West, albeit in a fragmented and functionally differentiated way among public and private institutions.’ It is, as he notes, in some respects simply an extension of the methods of education into adulthood and beyond. All that is necessary is for the state to co-opt and mimic the use of information systems already familiarised by the private sector.

‘It’s tempting to think this government overreach is purely reserved to China, after all they did just forfeit significant freedom by electing Xi Jinping president for life. This is incorrect thinking. The rest of the world is steps away from trailing the Chinese into a surveillance state. . . With incredible data collection, the plumbing is already in place for such a system to take hold. Our tech companies catalogue large quantities of data on everyone.’

Whereas China tends towards centralisation, Backer holds, we can expect social credit systems in the West to remain the province of private enterprises, probably in partnership with state organs. It is unlikely, he says, that a centralised social credit system will emerge, ‘even as the aggregation of all social credit sub systems will effectively change the aggregate character of governance in Western societies.

‘That this has now been deeply embedded within the politics of the state is merely the acknowledgement of the growing popular taste for the expansion of the jurisdiction of the state into virtually every facet of life — and thought. And that appears to have opened a door [to a world] that technology has constructed, and the private sector has long inhabited . . . ‘

He refers to ‘the apparently unstoppable movement from government to governance and from law to algorithm.’

‘In the process, of course, social credit, or data driven governance and accounting-punishment-reward systems can significantly up-end the now century’s old structures of rule of law by effectively making its structures irrelevant.’ He speaks of the possibility of the ‘end of law’ and the redundancy of lawyers except as ‘technicians of a new system the lawyer no longer controls’. Alternatively, we may end up with a new form of law, focused on data. We are already halfway there — and with our own agreement — as the result of social media, insurance rebate schemes, loyalty programmes, and even the logic of some video games, which have already trained an entire generation ‘to see in such systems nothing either extraordinary or threatening’. Thanks to public nonchalance about data, much of the infrastructure of social credits system is already in place.

In Sweden, microchipping of humans — using similar technology to that used by vets to implant pets to ensure they can be located when they wander — has been in use for several years. As a result, says Backer, the transformation will not be experienced as tyrannical, but as ‘a different kind of contribution by the individual to the formulation of collective values.’

‘Consider,’ he suggests, ‘the individual in the territory of the enterprise. She is the sum of her shopping habits, her consumption of food and other objects. She may be reduced to the sum of her Netflix account or her reading purchases from iBooks or Amazon, the way that a corporation is sometimes reduced to little more than its financial statements. Her political views are understood as the sum of her donations to charities and her political affiliations. She becomes “real” only when seen against the accumulated consumptive choices she makes (one can consume politics and religion as easily as one consumes a bowl of porridge). But she is more than that — this aggregation of choices that re-incarnates the abstracted individual (in the face of collective rights) also opens the possibilities of judgement, discipline, and control. Judgement comes when the collective offers its view of the value (collectively) of the exercise of individual rights (eating fatty foods, drinking, viewing certain movies, etc.).’

‘It is only a matter of time,’ Backer anticipates, ‘before the state — together with the non-state sectors through which state power will be privatized — will begin to move aggressively not merely to “see” individuals as collections of data, but to use that data to make judgements about those individuals and choices, and to seek to both discipline and control. To that end, the algorithm will become the new statute, and the variable in econometrics the new basis of public opinion. We appear to be passing from the age of rights to the age of information-management, and from the age of collective responsibility and constraints to the age of collective management.’

Social credit, imposing a new sense of ‘social duty’ at every level of the social order, will also transform the relationship between the individual and the state — ‘from passive to active’. It offers not merely an add-on to society’s value systems and their policing, but a proactive cultural transformation. Backer makes a comparison with the process of telling flowers from weeds in a garden, a distinction which he says is ‘grounded not in fact but cultural decisions that may change with time.’ He notes that ‘all rating systems construct norms and values even as they appear to measure norms and values received from other sources. In a more general sense, the compliance function at the heart of social credit or rating systems is a function of both observation and the knowledge of being observed.’

Slyly, unobtrusively, social credit reverses the presumption of innocence, shifting the burden of proving compliance on to the citizen who, until further notice, becomes ‘the suspect’.

Backer: ‘Legal subjects must be made to obey. They are no longer presumed to do so unless evidence to the contrary is produced. And that compulsion no longer comes at the point of a gun or in the uttering of individual representations of the legitimate authority of the state. Instead, it comes through the gaze; systems of constant observation combined with a self-awareness of being constantly observed that together coerces a particular set of behaviors tied to the character of the observation.’

The ethics of data raise many tricky questions. Who will harvest it? Who will choose the criteria? Will it be provided by those to whom it relates, by the state or by some independent agency? How will it be retained and for how long?

Backer maintains a somewhat ironic tone of imperturbability in the face of what might seem a dark and radical plan to enable the state to spy on its citizens and control the granular structure of their lives. Typically, he observes: ‘While the control element of law and regulation is grounded in command obedience, the control elements of a social credit and ratings systems are grounded in assessment, incentive and compliance. That fundamental difference in form does not change the character of the objective, just the means to its realization.’

Consumer culture has already done much of the heavy lifting in this area. We have come to think of technological eavesdropping as just one of the collateral aspects of the information society, and not a particular bothersome one at that. Any remaining reservations can soon be ironed out by propaganda.

Backer rhetorically asks: ‘Would it be possible for the state to develop systems for the enforcement of laws (criminal and regulatory) that depend on intelligence by inducing the masses to serve as positive contributors of data necessary for enforcement or regulation?’

The answer, in Western liberal democracies, he says, ‘may depend on the ability of the great culture management machinery of Western society — its television, movies and other related media — to develop a narrative in which such activity is naturalized within Western culture.’

We will more readily become persuaded by becoming convinced that, in surrendering further chunks of our privacy, we are engaged in a virtuous endeavour to catch lawbreakers and reduce wrongdoing.

He appears sanguine about the ethical and civil-liberties dimensions. ‘There is little by way of passivity here. What some have taken for passivity in the face of the algorithm may instead be better understood . . . as the reconstitution of humanity from individuals with souls moving toward collective characteristics, to the reconstitution of individuals as the aggregation of data driven traits that matter. But these are not inserted into passive humans but embraced by those who see in the “bargain” an advantage that suits their interests . . .’

In this new and heavily camouflaged tyranny, we shall become as children whose whims are pandered to for as long as they acquiesce in the ruling ideology. Individualism, personal identity, rights, equality and, above all, freedom are extended provided that (a) there is no conflict with the ruling ideological ethos; and (b) the 'equality' in question is as defined and laid down in the unwritten but well-ventilated rules.

The rights and freedoms extended in the name of Cultural Marxism are now implicitly understood to derive from the munificence of the state, rather than from any prior source, or from within the human person himself. They are concessions by the power, of whose generosity and enlightenment they represent incontrovertible evidence. The Faustian pact thus signed between the citizen and the state, the fixedness of the relationship between the two, and the limits it lays down remain obscured behind a rhetoric and agenda of freedom that appears to be irrefutable but is hugely conditional.

To call this a tyranny risks ridicule, but only such a word is capable of adequately capturing its scope and nature. It is unlike the classical tyrannies in that its use of force is covert and contingent. For the most part it protects itself by enabling the distraction or anaesthetisation of its subjects. In the minority of cases where this fails, it is capable of summoning up a mob to denounce, shame and ostracise. After this, for the determined dissenter, lies banishment and, where necessary, the threat of criminalisation and all this entails.

Perhaps, already, our sense of the meaning of freedom has been changed by the attrition of consumer satisfaction? Perhaps we have already traded the idea that our rights are necessarily something defined quasi-absolutely for an idea that rights are simply a reflection of the aggregate collective expression of desire. We live in a virtual world, hiding from the real one. This feels free, but only because we have increasingly unreliable models with which to compare it. Reality begins to fade from our memories, and gradually we are enslaved to the will of those who wish to exploit us more effectively.

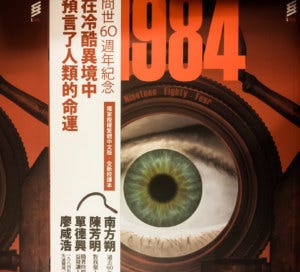

The prophecy of this totalitarianism is to be found not, as is often suggested, in George Orwell’s 1984, but in Aldous Huxley’s 1931 novel Brave New World. Whereas Orwell anticipated a world dominated by torture and terror, Huxley foresaw humanity imprisoned by seduction, sedation, and diversion. Set in London in A.D. 2540, Brave New World anticipated subsequent developments in sleep-learning and psychological manipulation being used to impose the will of the few upon the many. Huxley's society is run by a benevolent dictatorship, its subjects kept in a state of pseudo-contentment by conditioning and a drug called Soma.

Before long we may hear ourselves, by way of justification, asking: Why have we come to believe that we have a right to expect freedom? What if unfreedom is the natural state of man, broken only occasionally by relatively brief successful stabs at building civilisations? Perhaps this perspective is the truer one, but we have only lately stumbled into it after a lengthy reprieve from such understandings.

To cop the benign tyranny of our brave new panopticon world, we need but reflect on things that start off being one thing and quickly become another. Remember Google’s original motto ‘Don’t be evil’, which has now acquired exponential layers of unintended irony? One of the symptoms of our emerging condition is that, whereas many of our freedoms are increasingly circumscribed, these constrictions are quickly redefined and understood as newer and better freedoms. The Internet began as a parallel world promising near total liberty; now it is the watchtower of an undeclared regime increasingly intoxicated by its power.

We may have already traded the belief that our rights are defined absolutely for the idea that rights are simply a reflection of the aggregate collective expression of desire. It is certainly already much, much later than we think.