The Path to Profane Transcendence

In the bunker we have constructed to hide from the Mystery of existence, we cling to ‘rational’ understandings that please our egos but not our hearts. And the outcome may not be what we imagine.

On Good Friday 2011, less than two hours before the celebration of the Passion of Christ at 3pm, I listened to a radio discussion on RTÉ’s News at One, which purported to be about the condition of Irish Catholicism. The participants were an agnostic religious affairs correspondent, a Marxist sociologist, a campaigning neo-atheist and a watery Jesuit who began his contribution by making a poor-taste joke about a certain retired cleric, presumably to ingratiate himself with his fellow panellists. The entire discussion was predicated on assessing the progress of the destruction of Irish Catholicism, and the subtext implied that this was inevitable and would, once achieved, be a beneficial development. Far from showing respect for the day that was in it, there was not even the slightest sense that Irish society might have any desire to explore questions of faith in an intelligent way, or that there might be ways of looking at religion that were not either hostile or patronizing.

The nearest we got to a question based on attachment to or affection for Christianity was this, directed at the neo-atheist: ‘Can you understand why, at a time when a lot of people in this country are going through hardship, economic or otherwise, are questioning where things went wrong, where they’re going to go next, that they naturally sometimes tend to lean towards religion as a way of either filling that gap or of answering those questions for themselves?’ In other words, could the neo-atheist not understand that people still had a need to cling to superstition, in defiance of ‘reality’? This, on a discussion at lunchtime on the national radio station in a Christian country, was the nearest thing on offer to a concern about the disintegration of the culture on which future Irish children might hope to depend for their lives and hopes.

The last thing the hosts of such discussions desire is that the discussion be restored to its proper context. To make it personal; because I had already written two books exploring how intelligent people might re-engage with Christianity in its true essence, there was absolutely zero prospect of my being invited to participate in such gatherings. Today, hundreds of thousands of Irish Catholics may still troop into churches, but the dominant conversation they have been listening to on a daily basis for at least 30 years has put them on notice that their beliefs are, culturally at least, on the point of obsolescence.

Around the same time, I happened to watch a discussion on TV3’s current affairs programme Tonight with Vincent Browne, which likewise presented itself as exploring ‘the state of Irish Catholicism now.’ It followed the same format and style as a hundred other such programmes over the previous few years. Again, there were four panellists: a priest, the same religious correspondent as before, a visiting journalist/theologian from the United States, a female victim of clerical abuse. The premise of the programme appeared to be that the condition of Irish Catholicism was purely a matter of the strength of the institutional church, and that it was only a matter of time before this collapsed. Although a clear antagonism towards the church was implicit in the entirety of the programme’s tone and content, there was also the sense that the only thing at issue was the question of the church’s chances of survival. There was a very strong undercurrent of glee on this score, on account of the driving assumption that the church was now in deep trouble.

The presenter, Vincent Browne, although supposed to be merely the facilitator, was really the main protagonist in the debate, joining in with obvious approval whenever anyone said something he agreed with, and barracking anyone who tried to take the discussion deeper, which he was only rarely called upon to do. It was clear, and not for the first time, that Vincent Browne harboured a deep antagonism towards the Catholic Church, and indeed towards the very idea of religious faith, certainly in a Christian context. The agnostic religious correspondent seemed to be there to save Vincent’s wind, outlining a pessimistic analysis of Irish Catholicism that the presenter appeared to approve of absolutely. The abuse victim supplied the noises abuse victims are always called upon to supply. The priest appeared to be anxious not to enrage his host. The American journalist/theologian seemed confused, as though wondering what he was doing there, and in the end simply went with the flow.

Most of the programme, yet again, was taken up with discussion of the fall-out from the clerical abuse scandals. Nothing new was said and the discussion therefore did no more than lay down another layer of hostility towards the Irish Catholic Church. It was an intensely boring exchange, which seemed to perceive no function for itself other than to make more of the same old noises in order to send out the message that the participants were tough on clerical abuse and tough on the causes of clerical abuse. There was a brief discussion about the then pontiff, Pope Benedict XVI, about whom — with the exception of the American journalist/theologian — nobody appeared to know much, nor care in the least. Impregnating this segment was a deep condescension, as though the pope was some kind of ridiculous figure.

It is hard to see how a subject which offers the most scintillating possibilities for penetrating the mysteries of human existence and our understandings of it could possibly become so reduced other than by the replacement of editorial objectives with ideological ones. It is as though the producers sat down at their planning meeting and pondered the question of how they were going to avoid this potentially interesting subject becoming in the slightest degree invigorating or engaging.

At least up to the time I stopped listening and watching, about seven or eight years ago, the same pattern applied to virtually every radio and television programme that purported to delve into this topic. The usual approach was to line up various opponents of the Church, faith, and transcendent understanding in a kind of dramatisation of the continuing resolve of those orchestrating and conducting our public conversation to dump all over the core questions of existence. If, for example, you were to go back through the RTÉ archives for the previous decade or so before that point, you would find that perhaps half a dozen names had completely monopolised all discussions on Catholicism and faith in Irish society, and that, for the most part, all of these were either agnostics, atheists or, at best, lukewarm advocates of a strangled form of Catholicism that sought all the while to deconstruct and denounce itself in public as a sign of atonement. You might stumble upon the occasional tokenistic defender of the faith, but for the most part the participants were people who clearly have no desire for Catholicism to continue in any form — people whose entire interest in religion appeared to centre on their repugnance of it, and the ideological or neurotic grievance they nurtured towards it.

Only rarely in such discussions did we hear a voice articulating the human stake in the questions being discussed, by talking about human hoping, longing, meaning, freedom, infinity, authentic reason, or love. If you were to imagine a society created by the usual participants in such programmes, you could only presume that it would contain nothing like the Catholic Church and nothing of faith. That such a society would not survive for very long is neither here nor there, since, in the view of this entire constituency, this would undoubtedly be an excellent thing.

But my real objection to such discussions in that period related to their betrayal of the fundamental principles of journalism, by depriving people of inspiration, affirmations or enlightenment. My sense of what journalism should be, and might be if it were in the hands of openly thinking people, was grossly offended by such programmes, which really did no more than rehash, time and time again, a ritual of dissociation.

The saga of abuse by clerics of the Catholic Church is a dreadful stain on the history of Irish Catholicism, involving massive betrayals of trust and authority, but it is not the only important matter relating to the topic of faith in Irish life. Even here, the discussion was invariably constructed to exclude as far as possible the voices of those who, while in no way seeking to avoid what had occurred, desired a genuine renewal of the Church so that such things could be prevented from happening again. By definition, the discussion would be managed and conducted between people who appeared to wish for nothing less than to see Irish Catholicism buried at a crossroads with a stake through its heart.

Some short time before that, I had been at a function in Dublin at which there were present a lot of people involved in radio and television. Near the end of the evening, I was walking across the room — a very large room with hundreds of people in it from radio stations all over Ireland, national and local, producers and presenters, just about everyone involved in the industry you could think of — when I was drawn into conversation by a certain broadcasting ‘personality.’

As I was passing a particular table, an individual got up whom I recognised as the presenter of a programme on national radio, morning-time. The station he worked for at the time was largely devoted to pop music, and the show he presented was a mixture of light entertainment and harmless banter with an occasionally harder edge. I divined from something in his movement that he had stood up with the clear purpose of engaging with me.

I had been on his programme a few times, talking about politics and such things, though not in the recent past. He was a declared atheist, and on his radio programme and more generally was consistently very critical of the Catholic Church — you might say hostile. Not long before, he had attracted a lot of publicity by getting married in a humanist service. I liked him personally, but found his attitude somewhat condescending, and obsessively focussed on issues that he presumed people like me to be obsessive about.

He said something friendly by way of greeting, but immediately cut to the chase. A propos of nothing at all, he mentioned the name of a Catholic journalist, a man who would likely be identified by most people with the moralistic dimension of Catholicism — abortion, divorce and so forth. I knew that throwing in this other journalist’s name was just a way of introducing something. And I said: ‘Yes, of course I know him.’ Then he said: ‘You and he would be on the same page.’ I replied: ‘To a degree, sometimes’. To see where he was going I said: ‘You would have a different view, I think, to either of us?’ Then, immediately, he started to describe how he changed from being a Catholic to being a sceptic, agnostic, atheist. He described a funeral, many years before, of somebody who had died in tragic circumstances. There was a priest there, he said, speaking about the life of this man, and he recalled: ‘I listened to him describe his life and I could see that he was helping the family, because the guy had died in a terrible situation. I was really impressed and I thought “This is ingenious, they have appropriated something so fundamental, as the need of human beings for consolation, for reassurance.” But we have to move beyond that now, we have evolved to such an extent that this is no longer satisfactory for mankind to stay with. So we must face the facts of reality.’

I said: ‘But what is reality? Is this room reality? What is reality for you? Take this room away, take away the ground from under you, what is real then? Take away everything in your life, your family, your dog, your clothes, what is real?’

I briefly thought to myself: Wouldn’t it be interesting to have this kind of discussion on his radio show, but I knew this would never happen.

I said: ‘What I’m interested to know is why you want to prove your case so vehemently, why is it so important that you win the argument? Because all you will achieve at the end is to impose a despair upon everybody, invite everybody to confront the abyss which you imagine to be the end-point of everything.’

He said: ‘But everything’s fine, you just need to enjoy your life’. And I said: ‘But you are living in a civilization that for 1,500 years has been vivified by the Christian proposal, the idea of Jesus Christ, the Mystery made flesh. You cannot talk for certain about facing reality and assuming that everything currently in place will continue as it is, if you remain determined to remove the essence that has provided everything. It’s delusional to think that you can take Christ, Christianity, out of culture, and think that everything else will still be standing.’

He said: ‘We have to face facts’. I said: ‘You’re saying that even if the facts are dismal, we should still face them?’ He dodged this question and said: ‘The fact is that this stuff is just not true.’

I said: ‘Let’s leave the question of whether it’s true or not for the moment and talk about a different question: Is it real? Is there something real about it, first of all, before we ask whether it’s true? You agree from your experience at the funeral, that there’s something real, that it corresponds to something real in the desire of human beings? You can decide it’s a fabrication, but it’s still real. Then, let’s bring in the question of whether it’s true or not. Tell me: do you really think that something so correspondent to the real needs of human beings must necessarily be a fabrication? How would man engineer the creation of such a story?’

He said: ‘There are lots of smart people, there are smarter people than me, smarter people than you!’ I conceded that this was probably true. We laughed and our conversation ended more or less with that.

But I had this nagging feeling: that this man, who was in the position of speaking to the nation every day, had a particular view which cohered with the encroaching mentality of our time, but was neither thought out nor the result of a deep experience of reality. The situation out of which he spoke to the nation was not, most days at least, a situation of pain. It was not a situation of trouble. It was not a situation of facing the fear, grief and darkness that reality sometimes presents. I had no doubt that, like everyone, this man had his own dark moments and difficulties, but when he sat behind a microphone in a radio studio, his job involved not conveying anything of this to his listeners. His job, in a sense, was to engage in an avoidance of reality as it really, deeply is. This was the source of his livelihood — he was handsomely remunerated — and the purpose of his working life. And yet the impact of what the man put out every morning, by virtue of its essence, in the nature of its avoidance, was to increase the quotient of scepticism in the heart of every person listening in. Every day in the bunker as described by Pope Benedict XVI, in which we secrete ourselves in such as way as to place the Mystery out of our sight, we find ourselves, if we volunteer for it, under the sway of such people. In these ‘encounters,’ we are presented with a version of reality in which we can never get close to the answer because the question has been removed. Worse, it is implied by virtue of the absence of the question that there is no question. Worse again, we the listeners are invited to collude in this abolition of the question, which really amounts to the abolition of ourselves, because without the question there’s no reason for us to get out of bed in the morning. Thus, the question is eliminated from our culture, with our agreement and connivance, and we are seduced into embarking upon the initiation of our own disenchantment and obsolescence.

A relatively recent phenomenon of our newly-declared ‘rational’ era is the ‘religious’ programme on radio or television which is not really about religion at all but more about the personal ‘journey’ of someone — usually a celebrity or public figure — who has more often than not arrived at a position of scepticism or negative ‘certainty’ about faith and God. The problem with these programmes is not so much that they utilise dwindling resources of talent and schedule to provide a platform for the antithesis of religion, so much as that, in the superficiality of the conversations, the impression is conveyed that religion, even when considered under the heading of ‘Religious Programming,’ is not necessarily to be considered a plausible zone of concern for a modern-minded human being.

In the course of a series run over several recent years titled The Meaning of Life, which the national broadcaster, RTÉ, consistently promoted as a ‘religious’ programme, innumerable celebrities were persuaded to speak about their ‘journeys’ towards disbelief, including the former rock star and philanthropist Bob Geldof, the actor Gabriel Byrne, the author Maeve Binchy, the novelist Colm Töibïn, the airline magnate Richard Branson and the broadcaster Terry Wogan, singers Dana and Andrea Corr, businessman Ben Dunne, and the monk Mark Patrick Hederman.

This list of guests relates to a period stretching back from about the middle of the last decade, when the programme was presented by its original host, Gay Byrne, the longtime host of RTÉ’s Late Late Show, and long and widely regarded as one of the best talkshow hosts in the world, and also presenter of a weekday radio programme skirting between froth and the heaviest of matters, which had transfixed the nation for more than 20 years. Byrne died in 2019, and I understand has been replaced as presenter of The Meaning of Life by another broadcasting ‘personality,’ of whom the less said the better. Let us simply say that things are unlikely to have improved. From the very outset, and through multiple series, the programme conveyed an impression of treating the possibilities relating to the fundamental questions of life as having fallen foul of a recent revolution in thinking which left faith a more dubious concept than before, and like to continue to ‘evolve’ in that direction.

And these characteristics in themselves might not be so problematic were the various guests treated to a rigorous interrogation, from a religious position, as to how they had arrived at their various understandings. This never happened. The approach of the original presenter, Gay Byrne, was to simply prompt and prod his interviewees to expound on their experiences and settled positions. This gave rise to a number of rather worrying issues. One, obviously, was that, on a national broadcasting platform which had already washed the religious and the spiritual out of virtually every crevice of its everyday programming, those responsible for ‘religious’ programming seemed intent also on sub-dividing the content of their allocated timeslots more or less equally between those who claimed to believe and those who proudly asserted their unbelief. Another problem was that the absence at the heart of the programme of a specifically religious or even ‘spiritual’ agenda served to imply that, even under the heading of faith-programming, religion is something to be taken or left behind. Gay Byrne, in a 2010 Irish Times interview, when asked — in the context of presenting the programme — about the nature of his own faith, responded: ‘I am not going to say, because it would compromise me in terms of the show if people knew that I had a position. What you find is that they are all searching. No one has the truth.’

One guest on The Meaning of Life, the British comedian Stephen Fry, provoked a storm of sorts following his appearance on the programme on February 1st 2015. Fry pronounced himself an atheist, but entered rather enthusiastically into the spirit of the show’s ‘traditional’ last question about what he would say if it turned out he was wrong and found himself face to face with God on the Day of Judgment.

‘I would say: Bone cancer in children?’ he replied. ‘What’s that about? How dare you create a world in which there is such misery? It’s not our fault? It’s not right. It’s utterly, utterly evil. Why should I respect a capricious, mean- minded, stupid god who creates a world which is so full of injustice and pain?

He continued: ‘I wouldn’t want to get in on his terms. They are wrong. Because the god who created this universe, if it was created by god, is quite clearly a maniac, utter maniac. Totally selfish. We have to spend our life on our knees thanking him?! What kind of god would do that?

‘Yes, the world is very splendid’, he continued, ‘but it also has in it insects whose whole lifecycle is to burrow into the eyes of children and make them blind. They eat outwards from the eyes. Why? Why did you do that to us? You could easily have made a creation in which that didn’t exist. It is simply not acceptable.

‘It’s perfectly apparent that he is monstrous. Utterly monstrous and deserves no respect whatsoever. The moment you banish him, life becomes simpler, purer, cleaner, more worth living in my opinion.’

Within a week, the short clip, including some of this diatribe, which was released to promote the programme, had attracted more than five million views on YouTube. Twitter went mad, as only Twitter can.

Some Christians got their knickers in knots, taking offence at what Fry had said complaining about his ignorance of theology and pointing to what they claimed was the ‘contradiction’ of someone picking an argument with the god he doesn’t believe in.

But by far the more prevalent opinion was that expressed by other atheists, who appeared to think that Fry had said something novel and daring. They congratulated him for his ‘bravery’ and praised his ‘considerable mind.’ Some even suggested that Gay Byrne had been astounded and taken aback by what his guest had said, this idea being in harmony with the narrative of imputed radicalism being constructed around the ‘controversy’. Asked about the interview a short time afterwards, Gay Byrne declared: ‘I wasn’t in the least shocked. I was amused and pleased and realized he was being passionate about something.’

To give him his due, Fry himself, speaking a week later on BBC Radio 4’s Today show, said that he was ‘astonished’ that the interview caused ‘so viral an explosion.’ He said he didn’t think he’d said anything offensive. ‘I was merely saying things that many finer heads than mine have said for hundreds of years, as far back as the Greeks.

‘I never wished to offend anybody who is individually devout or pious, and indeed many Christians have been in touch with me to say that they are very glad that things should be talked about.’

Indeed, there was nothing particularly ‘offensive’ in anything Fry said. His was a ‘rational’ human response arising from a natural human confusion. He was quite within his entitlements to make such observations, and correct in saying that such observations had been made many times before — in pubs, in debating societies, from the mouths of children, even in books on theology, and in sundry other contexts. Fry was simply critiquing a particular understanding of the Christian God. His comments could hardly been seen as an attack on this God but rather on those humans who have promulgated such understandings as he found far-fetched. Fair enough. But the idea that this was some kind of radical, courageous outspokenness was risible. On the contrary, it was those who raised their voices to assert the existence and/or goodness of God who risked being pilloried in the modern Ireland of 2015, and this is even more true today. The commentaries of atheists, however hackneyed or reductive, are everywhere celebrated. The Meaning of Life could more appropriately be renamed The Meaninglessness of Life.

The far more interesting party to that conversation was the presenter, Gay Byrne. For many years, he had walked the tightrope overhead a culture that was cleaving not so much on questions of faith and rationality as on questions of identity in a climate of intense ideological warfare. On his radio show, Byrne was perhaps the most effective critic of Catholicism, occasionally doing things that cut to the core of the culture, such as his spectacular coverage of the Ann Lovett affair of 1983, when a teenage girl was found dead at the Marian grotto in the midlands town of Granard, having just delivered a dead baby that nobody else had known of. A week or so later, Byrne devoted his entire programme to readings of letters he had received on the matter from listeners, many of them heart-rending accounts of cruelty and mistreatment at the hands of priests and nuns.

And yet, Byrne could never have been described as ‘anti-Catholic,’ He frequently interviewed clerics and treated them with respect, some might even say deference. As an interviewer he had few peers, possessing an uncanny knack of drawing his subject into confessional mode. In part this was because he himself remained inscrutable, ambiguous. It was impossible to deduce where he might stand on almost anything though towards the end of his career this became less true, as it became more obvious that he had all the time been a closet liberal who was weary of Catholic Ireland.

Asked again about his own ‘spirituality’ in an Irish Times interview the week following the Fry kerfuffle, Byrne edged close to such self-revelation when he replied that he was ‘looking for certainty and looking for something to hang on to. And I’ve been brainwashed with all the other lovely Catholic people in Ireland, with the Christian Brothers.’

‘You don’t come through 10 years of the Christian Brothers without that making an impression on you,’ he continued. ‘It requires a very, very, very strong will to say, “I am finished with all that, I am casting it aside and I’ll have nothing further to do with it.” I haven’t got to that stage yet.’

A perfect bunker response to a bunker question. Anything he had believed hitherto was the result of ‘brainwashing,’ an experience he shared with all other Irish people. This is a core element of the ideology of atheism, and the mention of the Christian Brothers gave it an appropriate local colour. The second part of his answer strongly implied that he was close to the point of abandoning such notions, but didn’t have a strong enough will to finish the job. One gathered that Gay Byrne was teetering on the brink of declaring his atheism, but perhaps wasn’t ready to take the final step, because he hadn’t ‘got to that stage yet.’ The clear implication was that this ‘stage’ was inevitable, but that the power of the brainwashing effected by the Christian Brothers remained such as to prevent him, more than six decades later, from ‘casting it aside.’

Reading this at the time, I was reminded of an account given to me by a one-time journalist colleague of an encounter he had had one evening as he headed home from work in Dublin city centre. This journalist was, rather unusually, known for his Catholic faith and outlook, frequently writing on these themes on a range of print platforms and appearing also on broadcast media to bat for the Church or one of its positions or dogmas. One rainy winter’s night in the late 1990s, he was leaving his office when a man approached him wearing an over-sized anorak with the hood pulled up over his head. The man asked the journalist if he could talk to him for a few minutes, and the journalist immediately thought that he recognised the voice of the spectre addressing him. Crossing a bridge over the Liffey, the mystery man briefly pulled down the hood of his anorak so that the journalist could see his face. It was Gay Byrne — ‘Gaybo’, the ‘Father of the Nation.

Byrne outlined to the journalist a difficulty that had descended upon him in the recent years: While still wishing to remain a believer, he could no longer accept the divinity of Jesus. Could the journalist help him? They had one of those conversations which continue for an indeterminate time without either spatial or philosophical progress. In the end, pulling his hood about his face, Gaybo slipped back into the crowd. In such ways, we accidentally learn of the struggle and turmoil that may often underlie the glib certainties that issue forth via microphones from the broadcasting houses of the land.

One of the weirder aspects of the Irish media’s treatment of Christianity is that, on just two days of the year — Christmas Eve and Good Friday — something odd happens to the way Christianity is represented in the mainstream of our public conversation. For the rest of the year, the national newspapers and radio and television media treat Christianity and anything relating to it with a hostility tinged with contempt. They attack the value system, sneer at the beliefs and give unlimited space to the adversaries of Christianity to promote their agendas. Encountering this culture of hostility on a daily basis, the average Christian is moved to feel that he has somehow awoken from a deep sleep, to find himself in what might be a foreign country. While he slept, it seems, a whole new dispensation was ushered in, whereby Christ, or the narrative with which He intervened to alter the drift of history, is no longer entitled to respect, and perhaps no longer to be treated as credible at all.

But then, on these two days every year, it is as though the Christian has not been asleep after all. On each Good Friday, every Christmas Eve, the Christian picks up his newspaper and, idly scanning through the pithy bites of knowing nonsense that confront him as per usual, happens upon an editorial written to mark the day that is in it. It is as though a truce has occurred without being declared.

On Good Friday, the theme is usually the hope generated in the human heart by the Easter story. There will usually be some cautionary elements concerning some contemporaneous social or political events, perhaps some subdued disquiet about the history of clerical abuse. In recent times, these homilies have tended to connect — sometimes tortuously — the hope represented by Easter to the hope that is needed to turn around the economy, or some similar piety. The ‘most vulnerable’ will most likely get a passing mention, perhaps accompanied by an appropriate Biblical reference.

But the most striking thing will be the seriousness with which the Easter story is being taken. For the Christian reading the editorial, it is as though the editor of the newspaper has fallen asleep and had his place usurped by a resurrected C.S. Lewis. Almost invariably, it is high quality stuff; reflective and sincere, uplifting without being sentimental.

On Christmas Eve, the same thing occurs. Bethlehem, which for many months has implicitly been treated as the locus of some deluded and risible superstition, is presented as the womb out of which our civilisation was born.

This is most strange. On the one hand, one can rather straightforwardly dismiss the contradiction as arising from the exigencies of a busy newspaper office. A slot is there to be filled, and the occasion demands something special. It is, after all, Easter, or the ‘festive season.’ Since the readers of the newspaper will all be looking forward to the arrival of the Easter Bunny or Santa Claus, it would be churlish to ignore the moment. This is not a time for pedantic squabbles with tenets of what — nominally, at least — remains the majority faith. In view of the occasion that is in it, few readers will be likely to draw attention to the fact that the newspaper appears to be treating these themes in a manner inconsistent with the pattern that has persisted unbroken for the several months since the last ‘truce.’

Knowing what I know about newspaper offices, I have an intuitive sense of what happens. The Christmas Eve editorial goes on everyone’s list. Suggestions are welcome. Perhaps there is someone on the editorial staff with a knowledge of these matters, who can be prevailed upon to produce something appropriate — without prejudice, of course. Or perhaps someone has the phone number of a retired Church of Ireland canon, who can be trusted not to drop any inappropriate innuendos about abortion. Or perhaps — who knows — this is a project that the editor likes to reserve for himself. He still goes to Mass every Sunday, as it happens, but doesn’t like to make much of this around the office. And one of his degree subjects was theology, an interesting fact that he has managed discreetly to conceal from the majority of his journalists.

In any event, the editorial gets written, and duly appears in print. Reading such pieces myself, I have found myself moved in two directions. On the one hand, I would — each time — be tickled to the point of mild amusement. I would find myself wondering if anyone on the journalistic staff of the newspaper has remarked upon the incongruity of this sudden eruption of religious piety in the newspaper, or if there is a rump resisting such outbursts of apparent religiosity.

But I would also wonder about the impact of this kind of thing on other readers, especially those who belonged to what remained, in spite of everything, the majority faith of Irish people. Did they notice at all? Did what struck me as an incongruity fit effortlessly into their own sense of reality, in which religion was a matter for certain days and certain times of the day, and not to be taken seriously otherwise? Did the words and sentiments of the editorial find a harmony with their own mood, which had perhaps already, in anticipation of the special occasion to come, left the secular world and entered the realm of the holy? Was it, perhaps, that the consciousness of Bethlehem or Calvary remained essential to even a secular idea of Christmas/Easter, because without the rituals and iconography and — what?: legend?, fable?, mythology? — the enjoyment of this moment would be reduced?

I wondered about all this, and also about the fact that — as far as I could see — other people didn’t seem to wonder about it that much, or at least not publicly and in voices that could be heard, in the conversation that seemed to toy with every insignificant detail of everything else.

This is not an academic matter. It has to do with our culture's capacity to comprehend reality and convey that comprehension to itself, generating a body of cultural understandings which might be adapted by each human person who lives and breathes in that culture. It has to do with what reason, in the depths of itself, might really be; what 'evidence’ amounts to; what ‘intelligence’ is.

A strong subtext of much of the coverage, or non-coverage of these topics in the media, in my experience of observing this, is the idea that the passage of time somehow renders humankind more clever, more evolved and therefore understandably more amenable to ‘rational’ persuasion. But is this so? Does the fact that Bob Geldof has an iPhone make him self-evidently ‘cleverer’ than Augustine of Hippo? Our culture now speaks and behaves as if Augustine was a man doomed to misunderstand everything by virtue of the backwardness of the times in which he entered into history. If you ask the average man in the street about the relative reasonableness of the positions advanced by Augustine and, say, Stephen Fry, pushing him along a line of thought that requires him to invoke the kind of reason the general culture makes available to him, he has no option but to conclude that Fry, because he comes later, is self-evidently cleverer, whereas Augustine, because of the ‘datedness’ of his positions is — regrettably, perhaps, but nevertheless unavoidably — wrong about everything.

The real problem is not Bob Geldof or Stephen Fry, but the fact that, when one of these shamans of popular cultural celebrity delivers his ‘verdict,’ those whose job it is in those moments to stand guard over our culture in all its richness and truth do nothing to challenge what has been said, perhaps because they are incapable of articulating what needs to be asked. Thus, when the neo-monks of nothingnesss have finished speaking, there is nothing remaining but an echo that resounds all the way to the abyss we are building on the edge of our civilization.

I believe that the culture that we have arrived at in this respect is now deeply dangerous for our people, young and old, and for the future of our society. The idea that religion is something to be taken or left behind ignores the fact that the entire basis of what we regard as our civilization, including its capacity to hope, aspire and desire in healthy ways, can be traced back to Christian understandings of reality, and before that to Pagan practice and understanding. We speak here of thousands of years of nurturing the common metaphysical imagination. Today, this is being swept aside by a new wave of largely incoherent but fashionable understandings, whereby supposedly ‘intelligent’ voices speak all the time of their nihilism, and, in remaining unchallenged, are enabled to imply that nothing but nihilism is truly reasonable, intelligent or modern.

It grows worse. The examples I cite above are all a whisker from a decade in vintage, and this is not, from what I am hearing, merely because I no longer tune into the mainstream channels of propaganda. In more recent times, it seems that these questions have disappeared entirely, as though it were self-evident and axiomatic that all controversy of a metaphysical nature has been settled and it is now agreed that we have simply manifested here, randomly and without visible means of generation, other than a biological process comprehensible only on the basis of semantic constructs with their roots in vacant space. In this sleepwalk of unreason, we walk with a seeming confidence and cannot imagine why we do not feel it.

This is because, in spite of everything, in spite of ourselves, the questions remain, deep within us, implanted by God-knows-what, unanswered by the public certainties, hanging in the air all around. In the tumult of human interplay, we can forget about them for — sometimes — lengthy periods of time, but they accompany us in our private moments, in times of fear and grief and pain, in moments of Proustian provocation when the past looms up around us and seems to be not the past but the continuous present in which we have come to think of ourselves as flickering for a brief moment before . . . what? And then, perhaps, briefly deprived of our certitudes, we slip into an anorak and head into the streets of the secular city, looking for a face or a voice with which to trade the questions that define us, despite our best efforts to be defined by virtually anything besides.

In the past two years of the Covid debacle, we have had a windfall opportunity to observe some of the deeper consequences of all this. In the first place, it is questionable whether a truly religious-minded society would have fallen for the scam. After all, why be afraid of a respiratory illness if you have come to terms with your mortality and come to peace with our Maker?

As a species, it became clear, we had arrived in a dismal place, retreating into ourselves in a kind of fear that seemed new but was actually one that had been militated against for millennia and now was returning. It is a fear of reality that undoubtedly derives, at least in part, from a mysteriousness we intuit but refuse to acknowledge, and which is intrinsic to our existences and very beings as well. We are afraid of ourselves, or other people, or getting up and going to bed, of being alive, of death, and of everything in between. The result has been generations of people, ostensibly human, who no longer enter into life as humans have done virtually hitherto. They don’t know what life is for, what to do with themselves in their own lives, with the time that lies before them like a dirty chore, in which the only joys are added ones, the normal range of human feeling supplemented by substances and sensations — and in the caesuras between? Nothingness, or if not that, a dull, constant pain.

And, at a more prosaic level, there can be no doubt that the transference of what was once a vibrant faith in a Supreme Being to a tepid trust in shiny-suited politicians and their machinations has greatly reduced the human person from both his potential and the stature of his forebears. In the end, one might say, the missing part is not faith, or piety, or moral adherence, but imagination: the capacity to consider reality in all its totality, and find the correct balance within it.

One thing we have come to observe more attentively in the Time of Covid is the very real possibility that many things we had taken in reality and human existence for organic, spontaneous developments were the outcomes of interference and manipulation by what Thomas Sheridan calls the ‘secret unknowns.’ We thought, for example, that our education systems had simply gone to pot due to the general dissolution and some particularised neglect. Then we began to suspect that the entire process of debasement had been strategised and tabulated, implemented and refined. To what end? To the end of ending critical thinking in the human species, of reducing human thought to a singular soup of trivialities and nonsense. Similarly, we thought of the series of events leading to the corruption of our Fourth Estate(s) — the ubiquity of ‘journalism’ courses, the eruption of the world wide web, the defection of advertising to social media, the disintegration of the prior media business model — as unhappy happenstance. Now we see it was all carefully planned, constructed and assembled in place.

Perhaps we must spread our investigation wider. It is — is it not — astonishing the degree to which the Covid strategems and subterfuges have managed to tap into the leftover psychic paraphernalia of the religious way of being? Think of things like the craving for ritual, the rage for moral order — Commandments — of the self-blaming, self-flagellating urgings of the implanted notion of Original Sin. Think — in the context of Ukraine — of an enduring, long undirected will-to-compassion that sought to be good while no longer understanding where goodness lay. Morality, hope, empathy, imagination — all these qualities that we assume to be organically implanted, come to us in large part by dint of religious formation. When I was a child, the Church was for us a storybook, which we flicked through every day and intermittently immersed ourselves in. Then the neo-monks of nothingness set to work. And until recently we had assumed that their object was the obliteration of religion in all its possible forms.

But no. They wished, it is now clear, to destroy religion only in its sacred forms;

Now, it is as though, having been brought close to death in its original form, the religious impulse of humanity is being reawakened to some crystallising new purpose: the pursuit of a transcendence that is not sacred, but profane.

Our cultures think of secularism, as with Woke and mass migration, as a spontaneous phenomenon. But as we can see even from the above broadstroke sketch, quite a lot of work, time and moral tussle in public have gone into bringing it about and securing it. The outcome has been the snatching from the grasp of the coming generations the wherewithal to meet their own most fundamental desires. But that was but an interim outcome, a halfway house on the road to a new kind of world, in which a profane transhumanism might succeed, in one fell swoop, in abolishing both death and God.

In a recent article in First Things online, titled The Impossibility of Christian Transhumanism, Wesley J. Smith — host of the podcast Humanize, and chairman of the Discovery Institute’s Center on Human Exceptionalism — observes:

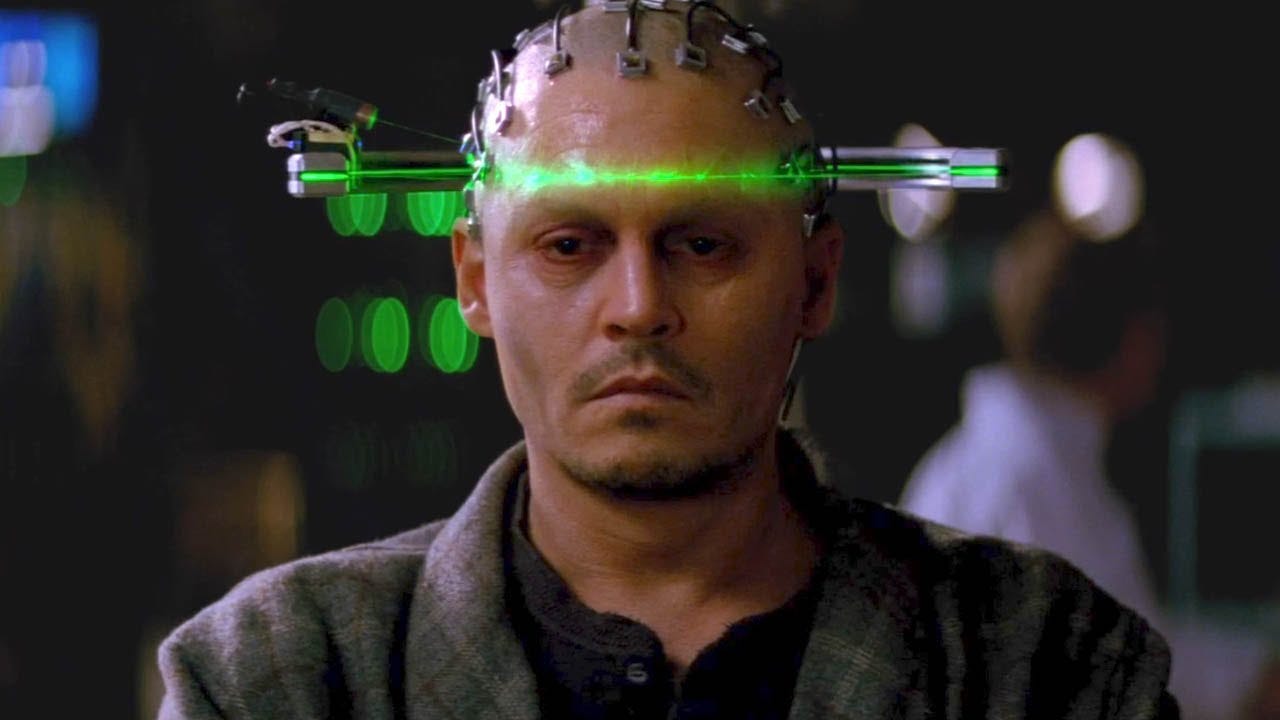

‘Transhumanism is a futuristic social movement. Its adherents believe that immortality is attainable in the corporeal world through the wonders of applied technology. The goal is to become “H+,” or more than human.’

We have dealt in some detail here with these concepts already — the allegedly approaching ‘moment of singularity,’ when the machines made by man edge ahead in intelligence; when the possibility of quasi-eternal life becomes real without requirement of decease.

Smith observes:

‘Removing God from the human equation engenders hopelessness and breeds nihilism. This is the crucial weakness of modern materialism, one that transhumanism seeks to remedy. By offering adherents the hope of technological rescue from the ultimate obliteration of death, transhumanism offers nonbelievers a postmodern twist on faith’s promise of eternal life. I can live forever, the transhumanist believes fervently, if we just develop the technology soon enough.’

His particular thesis here — he is critiquing an organisation calling itself the Christian Transhumanist Association — is that any attempt to blend this transhumanism with Christian concepts of transcendence would be massively misguided. ‘Transhumanist dogma is entirely materialistic,’ he notes. ‘Its focus is solipsistic, its purpose eugenic. Moreover, it rejects basic Christian tenets like sin, the need for divine forgiveness, the value of redemptive suffering, and eternal salvation.’

All true. But I think he is mistaken in believing that there is any serious desire to combine transhumanism with pre-existing religion. The point is to employ the husk of atropying pre-existing religion as a kind of booster rocket to launch an entirely new and discrete form of ‘transcendence.’ The association with the ‘old’ kind of religions needs to survive for but a short time. The purpose, as Smith indeed observes, is to turn human beings into gods. It is a utopian stratagem for human existence that seeks to usurp the powers of the hypothetical ‘Maker’ to place man’s destiny in the hands of men — not, mark, the destiny of each in his own hands, but the destinies of all men in the hands of a few. Smith cites the Transhumanist Bill of Rights, a crowdsourced document developed by the US Transhumanist Party, and adopted via electronic vote in December 2016: ‘All sentient entities are entitled to reproductive freedom, including through novel means such as the creation of mind clones, monoparent children, or benevolent artificial general intelligence.’

‘One can certainly be Christian, and as a secondary matter, a technophile,’ writes Smith. ‘But one cannot be a “Christian transhumanist.” The two religions — because that is essentially what transhumanism has become — simply cannot occupy the same space.’

That ‘space’ has now been more or less vacated, enabling us, in the pause before the next epoch, to contemplate and perhaps grasp why there has been so much talk of the implausibility of God. And in scattered clues such as adumbrated above, we can perhaps observe the cause and motivation for so much of the ceaseless, dogged work that has gone into dismantling and disintegrating existing notions of transcendence. The transcendent imagination of humanity has been stripped down to its chassis and is being rebuilt to an entirely different design.