'The Empty Raincoat' — 30 Years On

An old magazine or book functions as a kind of time capsule, which by virtue of its particularities, eccentricities and eclecticism can yield up three-dimensional emotional bromide-prints of the past.

World Without Empathy

What it is like now

Maybe we sometimes become unnecessarily inventive in our attempts to understand what is happening to the world — though especially to the West. Maybe it is simpler than it seems, even though its simplicity can sometimes be the most shocking, the most incomprehensible thing.

Beep-beep! The human race is being tooted to the effect that it must go into reverse. But the ‘elites’ will go forward, into what they assume will be a bright future. The world will become not merely two-speed, but duo-directional — forwards and backwards.

This is astounding. That the entirety of our democratic institutions have been dismantled as though under cover of darkness. Last night, they were there; today we got up and they are gone, and without any discussion, that we can recall, having occurred.

It was decided.

Just not by us.

It was decided that, since democracy was a failed system from the viewpoint of wealth accumulation, important decisions should no longer be referred to the people. The ‘elites’ made the decision themselves, by way of starting as they intended to go on.

The representatives of the people were present, after a fashion, but they were no longer — other than nominally — the representatives of the people. They looked now not outwards to their putative fellows, but upwards to the emperors in the gods. It was as if someone had reached down and unplugged the sovereign and authoritative energy of the people, and plugged in the stout cable emanating from above.

The ‘above’ is interesting, for it is a vantage point achieved not by democratic means but ordained on the basis of wealth — and therefore power — and self-election. But it should be acknowledged, in the interests of factuality, that the representatives of the people did not demur from this arrangement, and indeed undertook to ensure that the people would come to accept it also, marshalling all the instruments that had been put in place for the protection of the people, against the people.

It was the matter-of-fact manner in which all this was effected that made it, in a sense, mysterious. It was not a coup conducted with tanks and guns and armoured cars trundling into towns in the middle of the night. It occurred without sound or activity, so that it remained unclear exactly when it had been effected, or even if anything had happened at all. Hence the word ‘coup’ seemed inappropriate, and lent itself to disputation, if not derision. But the signs were there, not just in the diktats being issued by the former democratic leaders of the people, but in their altered demeanours, expressions and utterances. Now they spoke not as leaders of a government or a people, but as though the representatives, proxies, of an occupying power, which is in fact what — as though overnight — they had become.

For 46 months and counting, we have parsed, diced and spliced the possible explanations for the inexplicable: Why did our ‘liberal’ world collapse under the swat of the first rolled-up newspaper carrying the threat of an untested bug wrapped in a tissue of lies? Before this blow, everything collapsed: the conventions, the charters, the treaties, the constitutions, the rules of law, the laws of the earth, the sea and the skies. Nothing remained standing in those sunny days of April 2020, in the wake of the Ides of March, when all this seemed to happen as though on just another day at the office.

We have laid down, time and time again, the questions: Was it the slow disintegration of liberalism under the contamination of Marxism? Was it, purely and simply, the return of the repressed ghost of colonialism, seeking another chance to subdue and claim the world? Was it something to do with the relentless assault of the jackhammer of propaganda? Was it the slow insinuation in the human heart of a technical instinct of apprehension? Was it some long-hidden craving for authority that had somehow survived the attrition of the consumer society, the hedonism of the post-1960s West, the babble of modern pop culture, the constant talk of liberation, egalitarianism, equity, equality, diversity, plurality and rights? Was it some secret, undetected collapse of our constitutional republic(s) that became visible only when, as though with a rotten oak tree, someone passing thought to touch it with a finger and, the finger meeting no residual resistance, the Republic, like the tree, was toppled.

And did it not seem — if only for the sake of a coherent metaphor — that the undertones and undertows of all this suggested the brooding presence of some alien watchers, swaying to some different beat, tapping into invisible channels to effect their will via the venality of the morally lesser humans?

Or ought we just, as usual, recall and follow the advice of Deep Throat to Bob Woodward in that underground carpark, more than half a century ago: Follow the money?

Or, was it something set deep in human nature, some craving for authority mating with and wedding a long-suppressed lechery after power, the two finding common cause and mutual, consensual satisfaction?

Or all of the above, simultaneously and together, with the possible exception (for the sake of rationality) of the brooding alien watchers? Or not.

We pondered all these conundrums, and more. We tore out the remnants of our hair, and shredded the licences for our TVs. We made bonfires of our newspapers and magazines, which now seemed to take us for fools. But the mystery seemed to remain. All of these ‘explanations’ were in one way or another satisfactory in themselves, without appearing to crack open the puzzle, which remained more or less intact, even after we had pondered each one in turn.

What melted the resolve of the West?

Was it money? As simple as that? Something as old as, if not the hills, then certainly as old on the oak trees on the hills and the deep roots with which they plumbed the ground in which we imagined our civilisation to be abundantly founded?

Was it power chasing money or money chasing power, or a three-legged race between the two that overcame, surpassed, eclipsed and defeated everything we had taken for granted about the nature and structure of said civilisation?

We remember, or think we do, a mist of wistful yearning for a perfection of the crude freedoms we had carved out for ourselves — the non-stop talk of liberty and future that had accompanied our childhood playing, our teenage rebellion, our adult plans and schemes — but yet we had awoken one March morning to find it wrapped up and stamped and ready to be collected, having been sold by men in shiny suits that seemed to think themselves our owners and masters.

Those of us of a certain age were strikingly divided into those who were champing at the bit and foaming from the ears, and those who seemed barely to notice that anything had happened at all. This difference seemed to arise from what we had in common: that, at one stage or another, we had been crypto-lefties, to whom freedom meant more than something. Few of us had been to any significant degree ideological, but just thought left was kinder than right. Somewhere along the way, we had divided into those who regarded these sentiments as tickets to a seat at the table of power and influence, and those who, disenchanted, had drifted to what their erstwhile comrades called The Right and we — for I was one such — deemed simply The Middle Ground of Common Sense.

But, oh!, what fun we had, in those halcyon days of the Sixties/Seventies/Eighties, when we were young and innocent and free? Yes, free. We were all lefties then, all raging against ‘The Man,’ even though we were but vaguely aware of who ‘The Man’ might be. We raged against Thatcher also, and sometimes said she was a man too, and exalted Red Ken and Arthur Scargill. We lapped up Boys From the Blackstuff and, for a month in the autumn of ’82, were, all of us, Yosser Hughes. But that was not all we were. We were rebels and freedom-lovers, and liberals and luvvies (though not self-confessed). In June 1984, I travelled to Galway with the sole intention of shaking my fist at Ronald Reagan, on account of the US’s interference in Nicaragua and El Salvador. It was a highly successful trip. On Eyre Square, the President saw me from his passing car and, at first making to wave in my direction, seeing my clenched fist, turned sharply and waved to the far side of the street. I came home, tired but happy.

We did not just believe in freedom: freedom was the meaning of our existence, the freedom we enjoyed and the freedom we wished for ourselves and people we would never meet.

Though few have much to say on the matter, there is an imaginative difficulty in accessing the meaning, significance, even the reality of all this. It seems to be happening and yet could not possibly be happening. It is implausible, and yet it seems to be real. Plumbing its depths of strangeness and injustice is not easy, not least because this necessity is hardly ever or anywhere recognised. People who understand what has happened know that this is utterly unprecedented in the whole of human history; people who do not are oblivious to there being anything amiss at all. There are therefore, in a sense, two different ways of describing reality — one as something like the end of the world as we have known it; the other as just another day at the office.

We depend on the surrounding conversation to affirm what we understand as reality. When that is not present, or is radically corrupted, or is internally contradictory, the effect is to make us doubt at some non-specific level what we ‘know.’ We are cast adrift in a no-man’s-land of disbelief and confusion. We do not fall into the arms of the propagandists — we know to hate them because we know they are lying because we know what is true. But we also know that there is sometimes a difference between what is true and what is real, and that this is one of those times. Beliefs, even if clearly mistaken or wrong, acquire a certain weight by virtue of being stated by large numbers of people. And, no matter how strong your conviction concerning what you ‘know,’ it becomes something different to reality when it is contradicted by the perspectives, the demeanours and the silences of large numbers of the adjacent population.

All the things we ever said, all the things we claimed to believe, all the things we thought and taught — everything , from the whole of our lives and for a distance before them, stretching back into history — all has turned to dust. Web are as thoght children on our first day at school, ir not our first day on God’s Earth.

What It Used to be Like

The issue here is memory as a path to truth. In the miasma of a pseudo-reality, it becomes not merely harder to know what is true, but also, arising from the operation of certain escalatory mechanisms of that process of befuddlement, impossible to remember what the past was like as a measure of comparison with the present, so that one cannot any longer be certain that one’s sense of alienation is not simply being distorted by subjectivity. As we have been observing for the past 47 months, it is remarkable how easily people can be persuaded that things they took for granted in the past never actually happened, and that things that seem disturbing about the present arise from their own misperceptions and misrememberings. Manipulation of the news about the present can assist in creating this effect, as can a cessation or curtailment of talk about the past which, by virtue of being repeatedly denied, may increasingly seem to amount to muddled recollections or just still more misapprehensions.

Memory is a vital tool in keeping straight and sane in such circumstances. It would be easy to fall into a mode of thinking in which it had strayed beyond question that, for example, the menace and venom of the political class was a normal and habitual state of affairs. Given the unanimity of those holding official megaphones in conveying a singular perspective, it might even be easy to think that the hostility was in some way deserved, that we, the people (small ‘p’ now, in keeping with the overall temper) had deserved no less or no more. This, more or less, is what George Orwell meant when he cautioned that ‘who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.’

The difficulty is in retaining contact with the past so that its deep nature may be retained in a state of relatively intact recovery, in the event that some issue of dissonance arises as between past and present. It is a question of imagination, but even more so of feeling. What matters is not so much ‘the facts,’ though a grasp of facts may be highly germane, but of the capacity to reach and access the elusive feeling that derives from the incongruences between what is happening now and what experience and memory tell about what happened before. Something vital may be missing, causing a break in connection, so that I appear to be adrift in a dream (for which read ‘nightmare’) world, where all the physical topography is as it always appeared, but almost nothing that is happening within it makes any sense. It is as if there has been a rupture of logic, or human personality, or behavioural patterns, or . . . something. It is by no means clear what that ‘something’ is. People have changed, most of all those who hold the stage. They speak differently, using different forms of reasoning, different tonality, a novel edge of menace. They seem to have forgotten how things used to be, the way we used to take certain things as given, such as the sovereignty of the people, and the necessity to bear th enext election in mind at all times. But the changes are so integrated into the personalities of the newly empowered despots that they remain elusive to scrutiny. It is only in the overall feeling it evokes that the change manifests itself, and this is beyond description.

In seeking to plumb and parse these cricumstances, I find my old stacks of political and cultural and (even) music magazines from the 1970s and 1980s to be an invaluable tool of comparison, providing a yardstick by which the deviations can be measured and verified. There is something about an old magazine that is a little like looking through a window into a past time, and feeling the life that is there in all its clarity and authenticity. These magazines that I had almost begun to agree with my wife were a pointless waste of space have now revealed themselves as a vital instrument of combatting the pseudo-reality of 2024.

An old magazine functions as a kind of time capsule, which by virtue of its particularities, eccentricities and eclecticism can yield up three-dimensional emotional bromide-prints of the past. To scan or read an article from 40 or 60 years ago, and to derive from it a flavour of the sentiment and demeanour of its moment in time, and then to compare this — imaginatively, emotionally — with what the present feels like, is a strangely powerful thing. The sensations that result, with their dissonances and tensions and jarring ironies — can lead to new ways of understanding what has happened to make the present and its happenings what they are.

Books, too, of course, though they are less consistently reliable, since so many books are ‘timeless,’ especially novels, which is to say that, by virtue of being self-enclosed worlds, they tend to focus on longitudinal perspectives of the human condition, and do not vibrate in the same way with the official or political lives of nations. Old magazines, especially ones dealing with current affairs or cultural matters, are by far the most reliable hedge against the imposed amnesia of the present and the coming time.

Occasionally, though, one comes across a book that carries within it an unusual capacity for exploding capsules of truthful memory concerning what it was like before. Towards the end of last year, I came across, in a secondhand shop, a copy of a book I first read when it came out many years ago, and which I remember as having a profound impact on the thinking of that time — a time of growing uncertainty and discussion concerning the already shifting and heaving nature of the approaching future, chiefly in the realms of work, income, meaning and human dignity, as a consequence of the coming technological revolution. This book was published exactly 30 years ago, in 1994, a moment in history that has been mentioned by more than one observer as representing some kind of milestone at the end of the 1960s period of uncomplicated freedom, and the beginning of the era that preceded and laid the groundwork for the one that ended in or around the Ides of March 2020, when things started to get really serious.

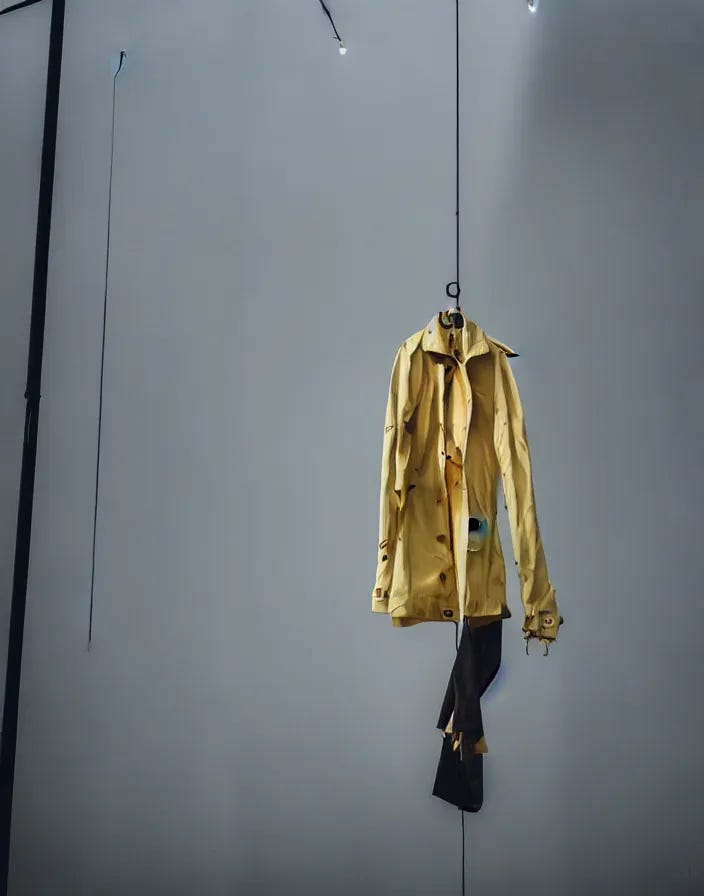

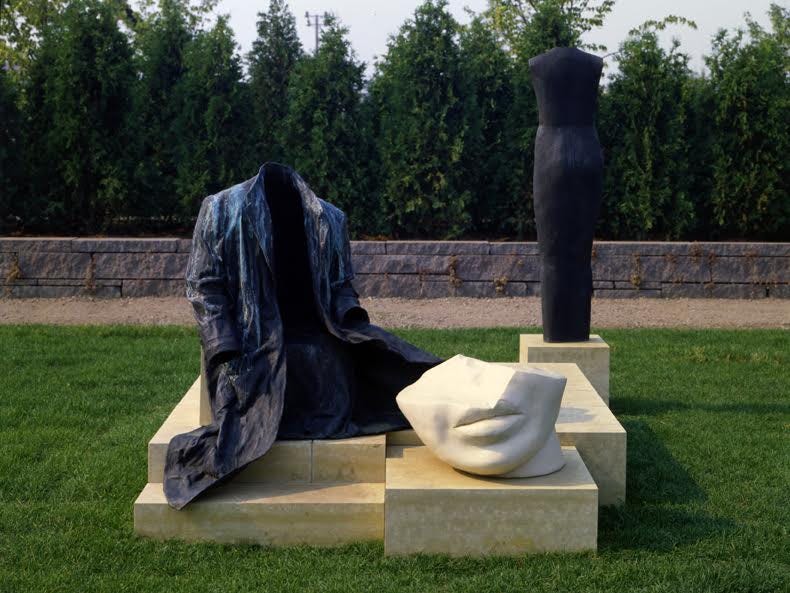

The book in question is The Empty Raincoat, by Charles Handy, a seminal cultural intervention that erupted into the world just at the moment when the dilemmas of the future world, economically and behaviourally, were beginning to be faced and considered, a handful of years before the dawn of the third millennium, which was to see shifts in human reality that were to make his book possibly far more vital to the future than it seemed at its moment of publication. The title refers to a figure Handy came across in an open-air sculpture in Minneapolis, USA, called ‘Without Words,’ by Judith Shea (see photograph below). It depicts a raincoat in bronze, upright but empty, representing the absent person, the disappearance of the human. Handy described it as the ‘symbol of our most pressing problem’.

Published in 1994, The Empty Raincoat — subtitled ‘New Thinking For a New World’ — is a book that, in large part because of its title, contrived to spark a moment of democratic wondering between the economic crises of the 1980s and the unknowable future lying mysteriously ahead. It is one of those books that you ‘remember’ in a certain way — in one sense as banal, almost, as a textbook of management theory, but which withal catered to the everyday public imagination in its time — and which now surprises you when you revisit it at a 30-year remove because it reveals itself as having spoken in its moment of exploding to more than was actually known at the time of its publication. It fingered a pulse in Western society that had become alert to the possibility of human obsolescence arising from technological advancement and the problems accruing therefrom, but later was to become seduced out of this wakefulness. In this sense, it acts as a useful mnemonic of the moments before we entered the present phase, with the escalation of ‘prosperity' from the mid-1990s, culminating in the crash of 2008, and then the rapid slide down the totalitarian hill to 2020.

Handy wrote:

‘What is happening in our mature societies is much more fundamental, confusing and distressing than I had expected. It is that confusion which I am addressing in this book. Part of the confusion stems from our pursuit of efficiency and economic growth, in the conviction that these are the necessary ingredients of progress. In the pursuit of these goals we can be tempted to forget that it is we, we individual men and women, who should be the measure of all things, not made to measure for something else. It is easy to lose ourselves in efficiency, to treat that efficiency as an end in itself and not a means to other ends.’

In that brief paragraph we see captured a snapshot of both the optimism and naïveté that characterised human culture up until a few short years ago, in which the assumption of human centrality to human-constructed civilisation and its value-systems — including democracy and constitutional republicanism — was implicit in everything within the publie realm that was not conerened with transcendence, a time when politicians were axiomatically understood as the servants of their electorates, when the purpose of politics was to support and exalt human endeavour and happiness, and when the point of economics — the ‘science’ of economy — was to serve, first, foremost and last, the needs and desires of human beings.

It is mildly shocking to read it now and to think that he might have writen the above paragraph in the expectation that it would meet with approval not just from those who might read it but either the society as a whole, from top to bottom. Reading it in a moment so far removed from such thinking, it is necessary to adjust focus, to twiddle the tuning knob, to crouch down in the undergrowth and watch this strange creature of human thinking mooch about in its territory, oblivious that it is being observed from a temporal distance of three decades.

It is quite shocking to contemplate these words in the very cold light of 2024, at a time when control of previously undreamt-of technology has fallen into the hands of a tiny elite of ruthless men; when the World Economic Forum (WEF — the ‘motherWEFfers’), having claimed authority over humanity without accruing a single vote, has ordained that, in the near future, we will own nothing and be happy; and when the political establishments of all the Western ‘democracies’ have folded before all such demands, and the agencies and resources of states are being marshalled to enforce the operational diktats that have been formulated to make all these things happen.

If you were to conduct, using Charles Handy’s book, one of those imaginative exercises in comparison — as between the period in which he wrote his book and the present — you might find yourself at the end of the experiment with two words battling for space in your head — one from 1994, the other from the present.

The word I might choose to describe the sentiment and demeanour of The Empty Raincoat is elusive in its particularity, but approximately accessible in its intonation: ‘Compassion’? ‘Ministration’? ’Kindness’? ‘Love’ (in its broadest senses)? ‘Humanity’?

The ‘empty raincoat’ motif was not so much a warning of human obsolescence in the obvious sense of a decline into practical uselessness by virtue of technological replacement, but more a warning about the loss of creative human agency to the organisational behemoth.

But something attracts me about the book’s title that I do not wholly understand. It is mysteriously evocative, especially for a book ostensibly about biz org, and remains a little odd even when you see it explained. I ‘get,’ more or less, the idea of the ‘empty raincoat’ — a foretelling of something like the threat of a disappearance of the qualities that brought our civilisation to the pitch it was at in 1994. But then I detect a resonance in his title that I am unsure as to whether Handy intended it.

Why did a book about business organisation (though not only that) come to have such widespread appeal? I wonder if it may be because people, at first sight, misread the title as ‘The Empathy Raincoat’ — for that, though meaningless, would have been closer to capturing the book’s tone, mood, demeanour and sensibility. With the addition to the word ‘Empty’ of an ‘a’ and a ‘h’ (ah!) the title seems to achieve a capturing of the total disposition of Handy’s time capsule.

The Empathy Raincoat is closer to what the book seems to say now, in 2024.

Empathy. Once this word came close to describing the general thrust and intonation of the vast majority of public contributions, whether in the form of books, articles, speeches, interviews, poems or songs. Sometimes this stream of good intentions could set off the tolerance alarms, but in general it was something that we mostly took for granted as the necessary soundtrack of a coexistence that we sensed to be precarious, volatile, and precious. The point, always, was to suggest ways in which this or that might be made better. The tone was such as to honour the common dignity of humanity and its striving for a more harmonious and auspicious co-existence.

In a pretty emblematic passage, Handy writes as though The Empathy Raincoat were indeed his title:

We misinterpreted Adam Smith's ideas to mean that if we each looked after our own interests, some ‘invisible hand' would mysteriously arrange things so that it all worked out for the best for all. We therefore promulgated the rights of the individual and freedom of choice for all. But without the accompanying requirements of self- restraint; without thought for one's neighbour, and one's grandchildren, such freedom becomes licence and then mere selfishness. Adam Smith, who was a professor of moral philosophy not of economics, built his theories on the basis of a moral community. Before he wrote A Theory of the Wealth of Nations, he had written his definitive work — A Theory of Moral Sentiments — arguing that a stable society was based on ‘sympathy,' a moral duty to have regard for your fellow human beings. The market is a mechanism for sorting the efficient from the inefficient, it is not a substitute for responsibility.

The one-word signal reaching us from 1994, then, might be something like ‘sympathy’/ ‘empathy’ — some ‘bottom-line’ sense that, when Handy was writing his book, he was trying to ensure the the future would be better for human beings, above all that he was taking it for granted that caring about the condition of the human race into the future was a worthy and proper disposition for an author to adopt.

Nothing could be further from the kind of words we might arrive at now, by way of capturing the essence of where, just 30 years later, our societies have fetched up. I’m almost reluctant to say it, but there can surely be no controversy at this stage about the suggestion that any meditation upon the present would be bound to yield a word such as ‘control,’ or ‘enforcement’, or ’menace,’ or ‘malevolence,’ as a means of naming the dominant note of the culture we inhabit.

The idea of public officials, politicians or health tzars lining up to issue diktats to the people about their presumptions concerning rights, entitlements and freedoms; about the requirement for radical amendments in their behaviours and expectations; about the imminent threats of diseases (how would they know?) and wars, (ditto); about the requirement to moderate their opinions and arrest their thoughts well short of utterance — such things would in 1994 have generated shock waves throughout our societies, to be interpreted instinctively as announcing the onset of some kind of mock dystopia, some contrived hoax calculated to test the alarm systems or rehearse the fire drills, to be followed by bursts of raucous laughter and exclamations of ‘Had you going there for awhile!’

The point of politics then was certainly not to berate or chastise people, still less to menace them, still less to belittle them on a daily basis by running their noses in their implicit inferiority to incoming migrants; their subordination to the demands of corporations; their worthlessness in the face of the machinations of rich, self-imagined overlords; and their powerlessness to resist the most radical and draconian attacks on the ways of life and being that has endured in human society for hundreds of years. For this, 30 years after Handy took a stab at sketching out a better future than the one he saw coming in 1994, is what we had now arrived to.

The even more chilling thing is that this state of affairs has been permitted to settle in upon us by a process of unspoken consensus. It appears to be taken for granted now by virtually everyone in the crucible of public conversation that the human race, as a whole — though especially its pasty-faced Caucasian incarnation in Europe, Australasia and the Americas — deserves to be constrained, divested, disparaged and punished. It is as a child who has been naughty and is therefore cast into disgrace and disapproval, though it is unclear who is arriving at these judgments — most of the time it is as though the culture is constructed in such a way that the errant ’child’ itself is required to be his own judge and dean of discipline. The population is reduced to a sullen silence, and yet is characterised by symptoms reminiscent of masochism and Stockholm syndrome, whereby the ‘leaders’ contrive to be cast in the roles of reluctant enforcers, who deliver the news of each successive privation in a tone of ‘this is going to hurt me more than it hurts you.’ And yet the snarl is always discernible behind the ostensible measured utterances, the fangs momentarily glimpsed flashing behind the mask of rationality, the ever-present sense of a regime that is fast losing its patience with people who think that freedom is more important than order, control and some unspecified process of retrbution.

We have good cause for nostalgia, surveying the long distance we have strayed from the conditions in Western civilisation in which Charles Handy wrote The Empty Raincoat, and even more in contemplating the abyss that separates us from the kind of world he was hoping might emerge.

Handy was — is (he is into his 90s now) — an organisational guru, and that is the main focus of the book: how organisations need to adapt themselves to the unknowable future. But there is a deeper thread: the shift in the nature of work and the opportunities the future appeared at that time to offer, whereby human beings might be able to reclaim their creativity in an emerging freelance economy in which no one would be confined to a singular mode of economic functioning, but each would have the possibility of maintaining a ‘portfolio’ of options. Deeper down, he digs into the question of existential self-sufficiency, the democratic yearning for possession of the means of human sustenance, which at the time was treated as something to be taken for granted, but has since revealed itself as as though terminally problematic as a result of the circumstantial transfer of the ownership and control of technology out of democratic hands.

When I worked as a newspaper columnist in the 1990s, these were intermittent themes of mine also, as they had been going back at least a decade before, to the time when I edited and wrote for a number of alternative magazines — generally left-leaning — in which these questions, and associated topics such as Universal Basic Income (then quite a benign proposition to provide a bedrock, no-strings, subsistence income for everyone) and the looming technological revolution, were rarely off the oped pages.

Back in 1994, Big Tech was unheard of, and to a high degree unimaginable. Companies like Apple and Microsoft were already in existence, but the Second Coming of Steve Jobs was as yet three years in the future, and the horses of habitual expectation remained undisturbed. At the time, the chief concern was with the conundrum of redistributing wealth and resources in a situation whereby machines might be doing most of the necessary work. There was some talk about ‘meaning’ and ‘human dignity,’ but not much about ownership and control. Indeed, there appeared to be a sense — perhaps arising from an exaggerated sensitivity provoked by the fall of communism — that technologies, regardless of their potential reach or effect, ought naturalistically to fall within the ownership of their creators. This, after all, had pretty much always been the way. There simply was no grasp of the implications of this proposal in the context about to dawn, or that what had always been so might no longer be sane.

In this context, we should recognise that Handy’s call for a ramping up of ‘sympathy’ was something more than a pious injunction. Already, a new wave of prosperity was sweeping across America, rendering it possible for markets to cater to the majority. Interest rates were falling from a spectacular high. There was a generalised expectation (spurious, as it turned out) of a democratisation of opportunity, that the rising tide would raise (nearly) all the boats. In these conditions, the traditional preacherly injunctions to ’be kind to others’ were already losing traction in an increasingly ideological world. Handy went on to bemoan the prevailing economic climate as one in which ‘the rich still get richer and the poor still get poorer,’ but his words ring hollow now, in a world where this process has in the interim escalated to such a monstrous degree that the words seem almost pitifully inadequate to capture the extent and scale of today’s abyss between the increasing stashes of the plutocrats and the diminishing chump change of the plebs. The roots of this problem rest not in an absence of compassion or charity, so much as in a deficit of observation and a paucity of thinking. The human race, taken altogether, took its eye off the ball and directed it elsewhere.

Handy captured the unspoken fears, inciting through his remarkable title many more readers than might ordinarily have read such a book. Although his title seems to contain a warning of what has since occurred, the book does not today read as though its author had more than a general and limited sense of what was going to unfold. His prognosis is rooted in its own time; it is not a foretelling of the future in which we have arrived. And yet, today, it reads as a sad record of a time when it was assumed that the human race, qua human race, would retain control of the means of its own survival and prospering, and that this was to be regarded as self-evidently necessary and beneficial.

On the question of prophecy, he wrote:

Prophets, in spite of their name, do not foretell the future. No one can do that, and no one should claim to do that. What prophets can do is to tell the truth as they see it. They can point to the emperor's lack of clothes, that things are not what people like to think they are. They can warn of dangers ahead if the course is not changed. They can, and often did, point their fingers at what they thought to be wrong, unjust or prejudiced. Most of all, they can offer a way of thinking about things, a way to clarify the dilemmas and concentrate the mind.

What the prophet cannot, and should not, do is to tell the doers what to do. That would be to take the power without the responsibility, the prerogative of the harlot, they used to say, not the prophet. It would be to steal other people’s decisions. The prophet can provide a chart but cannot dictate where or how the vessel should sail.

The chief value of the book for us today is in providing a point of solidity from which to engage in a measurement of the distance we have travelled under different headings, and using this to calculate where the most serious istakes might have been made. Throughout its text, The Empty Raincoat seems, almost naively, to assume that human society will always remain concerned about ensuring that the processes of work and production will remain centred on the well-being and furtherance of the human race, and the management of its endeavours on behalf of its own advancing and progression. This notion emerges from the text not so much as a stated verity but as an axiomatic assumption that needs no explicit articulation. It is ‘obvious’ — is it not? — that work and business will always occur, foremost and exclusively, for the good of humanity as a whole?

The central themes of the book include: the propositions that efficiency and profitability ought not be valued above the needs and deeper desires of human beings; that, in pursuing the ends, we should not ignore the damage often wrought by the means; that increasing consumption creates as many problems as it seems to ameliorate. that there is more to life than ‘winning’; that a stable society is based on people having regard for their neighbours. Time, he suggested, is of the essence — the same concept having opposite meanings for two categories of people. For the rich, time is money — they spend money to save time; for the poor, time is something they have to excess, something, as you might say, that they must ‘kill.’

Some of Handy’s thoughts now seem archaic and almost quaint, and yet he moves always to the centre of things.

We were not meant to stand alone. We need to belong to something or someone. Only where there is a mutual commitment will you find people prepared to deny themselves for the good of others. We, however, in our belief in liberalism and individualism, are wary of commitments. We look suspiciously at words like 'loyalty' and 'duty' and ‘obligation'.

Independence, whether we seek it or not, is being thrust upon us. Modern society knows no neighbours, said Disraeli more than a century ago, and it has been no different since. Loneliness may be the real disease of the next century, as we live alone, work alone and play alone, insulated by our modem, our Walkman or our television. The Italians may be wise to use the same word for both alone and lonely, for the first ultimately implies the second. It is no longer clear where we connect or to what we belong. If, however, we belong to nothing, the point of any striving is hard to see.

Chiefly, the material of the book centres on what Handy deems the ‘paradoxes’ of human economic endeavour, first and foremost among which is the understanding that, ‘if economic progress means that we become anonymous cogs in some great machine, then progress is an empty promise.’ In this sentence we can sense an implicit warning of a possible calamity that may befall us unless we are careful — the surrender to the technical, to the technologisation of the human; the amnesia about ‘peripheral’ issues of dignity and meaning; the sidelining of qualities like sympathy and empathy. Handy believes that every individual has to accept the challenge of filling their empty raincoat, which is to say make their lives meaningful in the context of what they do with their time. But there is no precise anticipation here of the scale of the impending collapse into a form of digital enslavement, whereby our entire lives would become as though directed through the prism of technological progress, and the apparatus of this process would come to be owned by a tiny elite of utterly insane despots and dilettantes who would come to regard the human race as just so many lab rats for their own use and amusement. Handy did not see this coming, and nor did anyone else; but Handy, nevertheless, by sensing something urgent that went beyond what was knowable, captured something that at least provides us now with a point of reference. In fact, at the core of his book is the argument that life is so full of paradox that future drifts cannot adequately be grasped or understood. In many respects, his book might be read as perhaps the last remonstrance of the old world that we so manifestly failed to pay sufficient to in its passing.

The purpose of this short series of article (at least one more to follow!) is rather a modest one: to draw attention to things that are either fairly obvious or discernible in plain sight, but also to underline the fact that what is ‘obvious’ has ceased to be the conventional wisdom, and that ‘plain sight’ has been replaced by a kind of hologram, chiefly converted by words and thoughts, that prevents many people seeing through to what is there — in other words, the ‘pseudo-reality’ of our frequent invocation, which draws us into the Lie and blocks us from seeing what is really happening. Charles Handy’s is not necessarily the best exhibit to attach to such a thesis, since, as he says, his wor is not (or was not) prophetic, at least not in the ‘normal’ (i.e. abnormal: 1984) way. But in another sense that is why I find it such a good example, since its predictive and sombre implications are, in a sense, ‘accidental.’ Handy was clearly presuming that Western civilisation would continue more or less as it had. He did not anticipate the present moment of rupture — very likely, such developments as we have seen of late years would have been unthinkable to him at that time. But herein resides the beauty (the word is not too strong) of his book for us now. For let us be under no illusion but that the Combine and their willing Creeps have the means of persuading the vast majority of the West’s population that before the advent of post-Covid tyranny and toxicity there was nothing but the same, going back into the mists of history, and Charles Handy’s memo to posterity tells us otherwise.

There are probably lots of books that are worth buying that provide a similar effect, though perhaps in subtly different ways. We should be especially alert for them in these troubled times, slipping into charity shops and jumble sales in the hope of finding who-knows-what. In a sense what we are talking about is reversing the concept of the fictional dystopia so that the benevolenet past, offering a kind of summoned-up makeshift ‘utopia,’ become available to be remembered or reimagined. This, being a matter of cultivating a new consensus, is different to nostalgia, which is largely a personal thing, and yet it has the power to merge and blend with that much-disparaged emotion of backward-looking sentimentality, as a way of reassuring us that we aren’t wrong in thinking that the world was not always a comprehensively evil place, that there is nothing ‘new’ or ’normal’ about neo-feudalism, and that ‘normal’ is — precisely — what human beings do when they do not have to do anything, i.e. when they are not ‘compelled,’ ‘coerced,’ or bullied into doing things inimical to their collective happiness and well-being.

[The second part of this article should appear next week.]

Buy John a beverage

If you are not a full subscriber but would like to support my work on Unchained with a small donation, please click on the ‘Buy John a beverage’ link above.