The Abolition of Reality

In grasping the meaning of this moment, the most compelling theory may be that of French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard: We have moved into a copy of reality bearing scant resemblance to the original.

The exhaustion of language in the face of the calamities of the past 40 months is the consequence not so much of a linguistic deficit of humanity, but a shocked response of humans to a sudden and gratuitous caprice of reality for reasons that no process of logic or reason seems quite able to explain. Words glance and skate off the surface of this new reality, unable to acquire the traction of meaning, or even the quality of gravity (both senses) to remain apropos. People say that everything has ‘gone crazy’, seeming to forget that they said the same thing many times when it wasn’t true, or not so true. Now that it is truer than true, the word ‘crazy’ is pathetically inadequate, as is ‘deranged’, or ‘bonkers’, or ‘lunatic’, or ‘mental’, or ‘cracked’, or ‘insane’, or ‘unhinged’, or ‘berserk’, or ‘batshit crazy’.

We hear ourselves saying that things have become ‘surreal’, but unconvincingly, because surreal is something we associated with molten clocks or dislocated toilet bowls, but now we are using it in everyday sentences in contexts it barely scratches the surface of.

Taking another tack, words that belonged in books and movies — like ‘dystopia’ and ‘gaslighting’ — have started to turn up in reality, like the booking agent has sent the wrong band to a children’s party.

For the past 40 months, drowning in seas of speculation, and what sometimes sounded — even to ourselves — like hyperbolising, we have struggled to form sentences to describe what has been happening to us. It often seemed like we had run out of words, so that even when we felt we had communicated something clear and cogent as a description of our situation, it fell some distance short of lassooing the matters we contemplated and provoking the anticipated sudden start of recognition in whatever bystanders might be within earshot. It was not just that everything was unprecedented and new, but that attempts at the articulation of descriptions of ‘reality’ seemed all the time to convey something else, something parallel or adjacent, but never quite synonymous or coterminous or correspondent.

There was something in the conduct of public agents — I mean not just politicians and civil servants, medical experts, scientists, et cetera, but also journalists, or whatever we might call them now — the established interpreters and mediators of reality, journaliars — that suggested an advance knowingness of everything they were telling us, accompanied by a sense of normalcy that grated with our experience and yet was strangely plausible. It was like we had entered some kind of nightmare vista, in which everything was being presented as though some kind of elaborate, pre-planned prank, perhaps for a birthday party or a retirement do, in which everyone was playing a scripted part and, any minute now, someone would lose his straight face, give way to giggles, and admit that it was a ruse and a hoax — just for a laugh — and didn’t they have us all going there for a while, haha haha haha ha ha?

Of course, this characterisation of things, though resonant in some respects, is cast, we might at first sight say, in entirely the wrong colours. It conjures up mischief in its mild forms, steeped in good humour, playfulness, affection, suppressed hilarity, whereas the forces and phenomena we deal with here are nothing like any of that. What we deal with here is mischief at the most malevolent level — the fixed grin of the intimate assassin; a mask of compassion upon a visage of pure evil; dark, grinning clownery that threatens to erupt into catastrophe, the deepest darkness that human beings can evince. Here we have encountered a ceaseless stream of deception of the most devious kind, an industrialised unleashing of the most systemic wickedness, a terror and a thieving of everything we had hitherto been able to take for granted in the modes of our security in, and familiarity with, and our feeling of being at home and at peace in the world. And all this at the hands of people whom we had nominated, elected and ordained as our representatives, trusting them with the keys of our sacred institutions and homelands and civilisations.

Here was, for certain, tyranny, though cast in the light of ‘saving lives’ and ‘the public interest’ and ‘the common good’. And here was death, both in the form of a constantly menaced prospect for which we were required to forfeit everything conceivable as life-enhancing, and, simultaneously, in the shape of a profoundly suspected, unmentionable and barely conceivable menace that seemed to be shadowing certain categories of people in certain types of situations — old people in nursing homes, for example, or those of any age who place their full trust in doctors, scientists and their government to tell them what was true and what was not. In the beginning, they spoke ceaselessly about the prospect that many people would die, and there was no evidence of it; and yet many people were soon dying in unprecedented numbers for reasons that were not permitted to be discussed or even mentioned.

A change came over people that caused them to go along rather than question. It was as though their brains had fallen out and splattered all over the ground, causing them no more than a moment’s pause before they continued as if nothing had happened. It was, in some way, like our nearest and dearest had suddenly started to act like villains from the scariest and most blood-curdling horror movie. What we were observing bore almost no relationship to what we had grown accustomed to in lives of whatever duration to date — except that the personnel who seemed to be in charge of events were familiar to us, and their manner only so slightly detectable as different: the merest uptick in menace, and yet such as to be unmistakable for anything else.

As it went on, it grew more and more sinister, and yet seemed at the same time to retain some element of continuity with the reality we had left behind. Figures whom we seemed certain in our recollection of their having spoken all their lives upon the value of liberty, and justice and free speech were suddenly speaking as though such ideas could no longer be contemplated — in ‘the public interest’ and for ‘the common good’. More and more, in innumerable sets of circumstances, the people we had appointed to represent our interests seemed to behave in the manner of a spouse seeking an alibi for a breach of trust and loyalty, turning upon us as though the fault for whatever was happening lay with ourselves.

We flirted with unfamiliar concepts: Mass formation, pseudo-reality, psychopathy, ponerology, groupthink, brainwashing, mass hypnosis, gaslighting. . . And yet none of these terms or concepts seemed to take us but part of the way to comprehension, or even to fit the circumstances or touch the meanings of events in a way that animated or vivified or activated things, or enabled us to describe more successfully to one another exactly what was happening and how we were feeling about it.

‘Gaslighting’, to take one example, was a word that seemed somehow to erupt into a previously unthinkable level of usage. A word that, in 2020, was already 82 years old but had yet to enter the popular lexicon, it had lain there, as though waiting for almost a century, practically unnoticed, minimally comprehended and under-utilised, and suddenly it was on everyone’s lips and fingertips, emerging to occupy a semantic space that nothing else seemed to fit or fill, which in turn had to mean that new or sharply unusual conditions had suddenly manifested underfoot. Suddenly it was everywhere. People would utter it with conviction and apparent confidence of its being instantly understood, and yet, at first, at least half of every gathering had to stop and ask one another what it meant. Within a few weeks, almost everyone was not merely aware of its meaning, but using it in every second sentence.

Its origin had been peculiar, to say the least. In 1938 there was this play, called Gas Light, and in 1940, and again in 1944, two films, from which the word had emerged in its semantic wholeness, but still lacking a general context. Up to the spring of 2020, it conveyed — or could be used as a space-filler for — a condition of human interaction that required a brief seminar of explication on the occasion of its every usage.

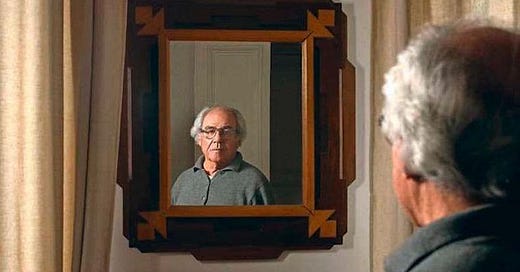

Hearing the word ‘gaslighting’ for the first time, a sharp bystander might deduce from the instant circumstances that it meant something like ‘taking someone for a fool’, or ‘driving the fool farther’, or perhaps ‘compelling someone to doubt his own sanity.’ But what had any of this to do with gas or the lighting thereof? In the play and the movies, the word alludes to the actions of an abusive husband, who gradually dims the gas lights in the family home, while pretending to his wife that nothing has changed, with the objective of causing her to doubt her own sanity, so he can commit her to an institution. The wife repeatedly asks her husband to confirm her perceptions about the dimming lights and other symptoms of his underhand chicanery, but he insists on the version of reality he is manufacturing.

Unless you had seen the play or one of the movies, you had no way of ‘feeling the meaning’ of the word, or using it without feeling a fraud. Almost nobody, as it turned out, had seen the play, and few had seen anything other than a short clip from one of the movies. It was the strangest word ever, and yet, in its strangeness, seemed to become more meaningful and piquant and appropriate, as though its impenetrability somehow assisted in describing things that had no rational description. By the middle of 2020, everyone, whether they had seen or even heard of the play or movies called Gas Light, knew exactly what gaslighting felt like. By that time, it had for weeks become the quasi-universal manner of describing the standard mode of communicating utilised by every politician, health spokesperson, officially accredited scientist, TV presenter and purchased journalist in the world. The word acquired a life of its own, remote from its cinematic context, with connotations of a kind of slow murder of the human spirit, and ultimately of the body, by something like lacerating and ultimately lethal lies. By then, we had the impression of being surrounded by walls of lies, as though the world had turned into the stage-set of a horror drama and we were children for the first time encountering such a phenomenon as theatre, but without prior warning that what we would experience would not really be real, so that it entered our souls as nothing had before, or perhaps in a manner in which, quite unprepared, like when we had attended our first ‘fit up’ play by a travelling theatre company that had inveigled its way into our junior school to perform on the day before the summer holidays were due to begin, and suddenly we found ourselves as the dumb witnesses to menaces and slyness and violence and murder, and other experiences we had never even dreamed of in the innocent lives we had lived hitherto. Each of us, in turn, looked to the others, hoping for signs of a mischievous fabrication, a deliberately-concocted drama, a jape, prank, a joke. But the faces of others gave us no comfort in our sense of the unreality and impossibility of what was afoot, and by their seriousness caused us to gradually drop our guileless smiles as we waited in confusion for some moment of clarity or revelation.

And so, more or less, things remain. For the past 40 months, we have struggled with words in our attempts to describe what has been happening to us and our world, mostly with so little success that we simply repeat the word ‘gaslighting’, as though it has become a kind of verbal pacifier. Such has been the unprecedented and shocking nature of events, almost on a daily basis, that we have struggled to find words adequate to describing our feelings, and more and more have opted for a bemused silence, which is slowly killing those who adopt it. Many among us have been unable even to diagnose the necessity for new ways of thinking about what is happening to us, or for new words to conduct that thinking in. We have been thinking, perhaps, that the words need to come first, but perhaps this is a mistake. Perhaps the constructs need to be sketched, so that new words volunteer themselves? Or perhaps it is time to address the possibility that the problem is not linguistic, but conceptual — not to do with the function of description, but with identifying the deep nature of some fundamental change that has taken place in the depths and folds of our societies and cultures. Perhaps this shift had been in place for a long time but escaped our notice because the circumstances thrown up by reality did not sufficiently engage the changed conditions to convey that things had ceased to be as they once were.

Nothing we have come up with yet seems quite adequate to the task of explication. Some explanations — the end of times, collective possession, mass hypnosis or brainwashing, a wave function collapse or some similar kind of disintegration and rebuilding of our temporal grid — seem for a time to be functional as metaphors but become implausible when placed against our subjective experiences and the habit we have formed of applying historical facts and logic to the comprehension of change. We have known nothing of these phenomena before — other than in plays or movies — so why should they invade our actual lived existences now? There is no explanation that seems completely to fit the narrative course our lives have followed through our childhoods, into adulthood and on to wherever we may find ourselves; and yet, the symptoms of radical change are everywhere, and most of all — as we are rapidly discovering — between our ears.

Something utterly new is occurring, something that, if happened before, happened in remote places or different epochs, so that no one is able to recall any point of reference to say that, ‘Oh, this is just like how it was way back when. . .’ And, because there is no such point of precedent, many of us feel obliged to take events at face value, to believe that a pandemic could happen without evidence in anything other than constant assertion; that a senile man could be elected president of the largest democracy in the world; that athletes have always died in great numbers but no one in authority had ever noticed before; that, after 150,000 years of human evolution, women and men are suddenly morphing seamlessly into one another; that a world which for several decades had fretted about the evils of child molestation has suddenly decided that children were not getting enough sex, and hurries accordingly to ensure that ugly old men dressed as female prostitutes are facilitated in waving their privates at five year-olds as part of their seducation — there, now, is a new word that fits — and that any incoherencies of any of this can be satisfactorily accounted for by accusing those giving voice to their bemusement of wearing (invisible) ‘tinfoil hats’ and making a nuisance of themselves for the sake of vexatiousness.

After 40 months of struggling with everything, committing more than two million words to the ether, I am only now beginning to develop a viewfinder through which to look at what has been happening. It has to do, I now believe, with a fundamental shift in the nature of reality, amounting to the abolition of reality as we have known it. After nearly three years of writing here on Substack, I now believe I have a sense of the theme and tone of the book I have felt I was writing from the beginning, which I now propose to proceed with under the working title: The Abolition of Reality.

‘Oh yeah, very original!', I hear the retort, ‘it’s The Matrix!’

Not really. In a recent Twitter conversation between Andrew Tate and Tucker Carlson, Tucker boasted that he had never seen the movie called The Matrix. Tate couldn’t believe it. I can go one better: I’ve seen half the first movie, at least twice, but couldn’t stay the course. I don’t like sci-fi, not because I’m not interested in the future, but because I am, and because I need the future to seem naturalistic, organic, not makey-uppy, like those essays we used to write in school back in the twentieth century about ‘Life in 2000 AD’, in which everybody would drive around in hovercraft and for their lunch eat one speckled pill at the centre of a large plate. I never feel that sci-fi in books or movies reflected adequately the way reality morphs and weaves through time, because it always misses the most striking aspects of those processes observed across the span of a life. A strange quirk of time in this sense is that it seems not to change anything much at all, day to day, year to year, or even decade to decade, in the continuous warp and weave of itself, and yet, whenever elements of the past manifest in the present, they — observed as though from a temporal distance — look improbably unlike how you remember them. If you look at a Mark One 1970 Ford Escort from behind on a 2023 streetscape, it looks unsafe and highly sprung, like a wobbly anorexic in a miniskirt, at once futuristic and impossibly antiquated, and you wonder if anyone could possible have designed a car like that and what were they thinking of. And yet, you have the clearest memory of envying your friend because, one day in 1971, his father drove one of these contraptions, replete with sports wheels and sheepskin seat covers, and a doggy in the rear window that nodded at the traffic coming behind.

If I look at the photograph of a streetscape from the 1980s, I don’t feel like it’s a place I came through, even when it’s of my hometown, and there are signs of constancy, like the church or the bridge near the dancehall, which make it unmistakable. I have no memories of being in such places, or seeing such strangely-shaped motor vehicles or such unspeakably unfashionably dressed people. Everything in it seems to be some kind of reaction to something that isn’t visible, as though it is some kind of fancy-dress demonstration born of perverseness, a form of burlesque of spite against a past that cannot be imagined but is obviously repudiated.

This appears to be a continuous feature of the evolution of human history. The past has come to look like something mad, as though it has yet to come; the present gives the impression that we stopped being able to imagine the future sufficiently even to write one of those essays, because the future is already invading the present at a pace that makes our imagined vistas look old-fashioned before they’ve come into focus. And yet, our experience of the present is as a condition unhinged and revolting. Time has seemed to bolt, to go to seed, like a field of cabbages, so that nothing remains useful, or meaningful, or hopeful.

The roots of these tricks of time and chronology seem to begin with the increasing technologisation of everyday reality, a relatively new concept in the sense that the devices now available appear to confer greater and faster evolutionary possibilities on the quotidian life of the average human being. The difficulty here is not about the complexity or unknowability of technology, but the capacity of the imagination to grasp things that are not yet, as it were, ‘discovered’ — in the sense that we are still experimenting with the last generation of technology by the time the next one comes along. We have time — if even this — only to figure out the operational functioning of our devices before they become obsolete, but all the while their cumulative effect is time-consuming, mind-changing, epoch-remaking and existentially radicalising in ways that we have no time or capacity to imagine. Our present is constantly undermined by the contingency of waiting for inventions that have not yet happened but cannot be avoided, which will change everything . . . again. Like, say, if in the 1970s, a group of myself and my contemporaries had been shown a piece of film that showed a streetscape from 2023 with people walking around it, with this indecipherable object glued to their ears or held out in front of them like a prayerbook, how long would it have taken us to figure out what it was?

The other day I asked my four year-old step-grandson, Kojak, what Twitter is, and he said: ‘It’s a place people go to send messages to people they don’t know.’

Perfect, especially the part about it being a place and, even more so, the part about sending messages to ‘people they don’t know’. Such concepts would have been unthinkable when I was his age. (Elon Musk needs to talk to our Kojak!) But to most users, Twitter is just Twitter, a tautology. We spit out words as though we know what they mean when at best we have only the flimsiest of understandings of their implications other than what we’ve gleaned from repeated hearings and our own repetitions of whatever we make of these.

Can you actually imagine what cyberspace is actually like? I mean, we know what it means — more or less: a kind of placeless place where words and images pass one another in something akin to space on their way between two people who have never met each other, or perhaps they have but it doesn’t change anything. All these memos and essays and prose poems and poetic poems and love letters and sexts and selfies and memes and immunology papers, all lightly bumping off one another — if they do — en route to an unimaginable number of destinations from an incomprehensible number of points of origin. But could you explain it to your grandmother? We comprehend cyberspace without understanding it. We imagine it, but in a fuzzy way that has no root or origin in, or relationship to, three-dimensional, concrete reality. Our imaginations are capable of assimilating this at least sufficiently for us to operate the relevant mechanisms, though probably no more. And yet, we cannot describe it, not in everyday sentences that provide the concepts that are necessary to comprehend it with the same level of concreteness as telling someone: ‘I fell off my bicycle at the bad bend before the red bridge on the hill between the church and the post office.’

In a similar way, we talk impressively and blithely about transhumanism and the singularity and having our heads chipped by Elon and the forthcoming new utopia of non-sacred transcendence, but in truth we literally do not know what we are talking about. We may use all the correct words and phrases, but we cannot imagine what this will be like, because it will not be ‘like’ anything we can currently imagine.

Consider this definition:

Transhumanism preaches the possibility of a technological enhancement of the human body, both through the use of technological prosthesis that by means of a life extension made possible by the use of genetics, biomedical engineering and nanotechnology. The ultimate goal of transhumanism is to completely overcome the need of a biological hardware through the integral fusion between man and machine made possible by mind-uploading, a technique that would pour out on a digital infrastructure the entire contents of the human mind.

The first sentence is relatively comprehensible. The second reads like nonsense.

But then, try thinking about trying to explain to your grandmother, even a decade ago, what transgenderism is. Yet, here it is, right up your street, and even your grandparents have to deal with it. I know, because I’m one of them, but at least I still have the capacity to know it is nonsense, whereas the ones who just have words to vaguely grasp its implications have others words with which to rationalise and accommodate to it: ‘You have to move with the times.’

The truth is that many things we take for granted in technological, technocratic reality are such that we feel compelled to accept and, in a sense, ‘comprehend’ them without actually understanding them or knowing how they work. Or, even if we do know how they work — in the sense that, perhaps as scientists or technologists, or just nerds or consumers, we know the lingo and the concepts and how they fit together, but how far into that reality does the understanding of all but a tiny few extend before they have to say something like, ‘Nanotechnology wasn’t part of my degree!’? Very often, when we delve into these areas we employ metaphors and analogies to aid the process of explaining ourselves, or even explaining to ourselves. Perhaps we have always lived in worlds that are over our heads, but — over time — managed to arrive at conceptual accommodation with them, blithely trotting out words and phrases that communicate our sense of their general meaning, even though we may be unable to penetrate them beyond the first layer of their actual nature and configuration and implications, and in reality merely re-generating the object in the form of words that ‘stand-in’ for it without capturing or describing its essence.

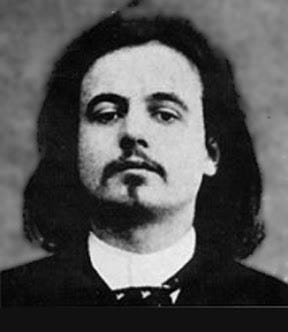

The late French philosopher, Jean Baudrillard, was both a poet and a prophet, though — appropriately — in different senses to those normally conjured up by those words. He was a prophet not in that he predicted the future, but that he predicted the future of the future, so that he was able to move ahead of it and coin sentences to describe not just what he saw but what it might mean. He is often described as a ‘postmodernist sociologist’, but this he denied vociferously, just as he rejected the idea that he remained in later life a Marxist. He was, in fact, more of a poet than he was any of those things, although I do not believe he wrote a poem in his life, despite inspiring more than a few of them.

It is as a prophet that we come to him here. He predicted the condition of the now, i.e. this moment in which you are reading this, but less in its specifics as in its general condition. Through the second half of the twentieth century, he recognised that the very essence of reality was about to change, or had already changed, under the attrition of technology, so that nothing we would henceforth encounter would be anything like what we had been used to, or what we might expect on that basis. By his own admission, he knew nothing of technology, but managed to see beyond the trees to the wood. His observations are therefore not really a function of foretelling but of observational logic and poetic witnessing of the changes in culture and life that have accompanied the technological revolution.

He wrote in prose but not in a manner suggested by the reductive implications of that word. Like all great poets he never actually said what he was saying, but trusted the words to resonate with the time that would come after, which they did and continue to do. It is not possible to find a single sentence or paragraph in his work in response to which one might say, ‘Ah! This is what he meant!’, but the sense of what he means is to be harvested cumulatively through immersion in his words. Really, he is not talking about events or developments in the world so much as a relocation of the centre of gravity of the world, culturally speaking, so that it can no longer be regarded as the same world depicted by history, and literature, and even science, with the further implication that its denizens can no longer be comprehended sociologically, or psychologically, or even intuitively.

What he suggests, reduced to a sketch, is that, as a result of the operation of tech, networks, laptops, smartphones, the internet and, by implication, social media (though he died just as this was getting off the ground), reality as we knew it had ceased to be and had been replaced by a ‘copy’ of itself, which was nothing like the original. It is strange that, in writing this article, something similar happened to the text containing my descriptions of reality and of Baudrillardism. I am writing it on a laptop, which provides me with a running wordcount. For no particular reason, through no inclination or instruction of mine, the file on which I was working offered me the option of making a copy of itself. This might have been an alarming moment, because I had no way of knowing — other than reading the 7,000+ words I had written in both the copy and the original — which was the most complete of the two. I found the original and noted that it had 7,567 words; I checked the copy and saw that it had 7,633. I chose to continue with the copy, abandoning the original to the condition of fossil. Now, my article is a copy of itself, and this is something like what Baudrillard suggests has happened with reality and the state of my being within it.

We have entered, he says, a ‘simulacrum’ of reality. Because of the fracturing of reality by technology and technological communications, it had become impossible to restore coherent patterns to events that had been ‘atomised’ by virtue of being processed, circulated and re-broadcast to the point of timelessness.

Outside of certain postmodern circles, it is commonplace for public commentary to assume that reality is something fixed in particular foundations, and therefore a phenomenon that media simply describe or analyse in the form it takes standing there. Baudrillard (though not only him), takes a different view: that the object standing there is as much the creation of the descriptions and representations as it is of any concrete process of production, and Baudrillard would correct me: ‘Much more’. The difficulty we have in comprehending this has to do with the relative slowness of the evolution from one form of reality to the other. Once upon a time, the object was indeed all there was; now, the object is merely a starting point, a fleeting entity that immediately becomes an image, and may no longer be there, or may have been, in the first place, an instrument of misdirection or a figment born of and reproduced by propaganda. Now, the image is all, and the imagination therefore the best instrument of comprehending reality.

Such is the strength of irony soaking Baudrillard’s prose that it is not possible to divine the precise location of his thinking in the spectrum stretching between metaphor and literalism. It seems clear that he is speaking metaphorically — but, then again, perhaps not. He never states or acknowledges that he is dealing in metaphor. Yet, nor does he fully explain the process by which such concepts as he depicts might have entered into reality as though material things, something that remains objectively unimaginable, if not impossible. But one thing we can say for certain is that his hypothesis, for all its fanciful aspects, offers an approximation of an explanation, or at least a contextualisation, for most of what is happening now, for what has been happening to us, for instance, in the past 40 months. The things occurring in 2023 that take our breath away if contemplated from the perspective of, say, 1989, are gradually becoming as though naturalistic. To elaborate on this sociologically or psychologically or politically seems to get us nowhere except spinning around in the same circle. If we think that we have slipped out of time, then no other explanation is required.

It is worth repeating for the sake of emphasis: It is hard to glean from his sentence how literally he intended his characterisation to be taken, or to grasp precisely the extent to which he may have meant them metaphorically, or even metaphysically — but the sense is that he is at least glancing off literalism. For someone who did not ‘know much about the subject’, he writes dazzlingly about the impact of technology on human consciousness and culture.

For Baudrillard, as a function of the forces he focused on, history had already ended. Picking a fight with the Italian writer, Elia Canetti, who in 1945, in the wake of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, claimed that mankind had vacated history having rendered it unreal, but would one day return, Baudrillard declared such a restoration impossible. Canetti’s view was that the bombings had eclipsed the Sun as the source of earthly human power: ‘[L]ight is dethroned, the atomic bomb has become the measure of all things. The tiniest thing has won: a paradox of power.’ And yet, Canetti remained optimistic: Balance would again be restored.

Baudrillard thought differently. Because of the fracturing of reality by technology and technological communications, he insisted, it had become impossible to restore coherent patterns to events that had been ‘atomised’ by virtue of being processed, circulated and re-broadcast to the point of an unstable timelessness. The indifference of the majority of humanity to either meaning or content as other than distraction, had caused history to slow down and fall even further behind. Again, it is difficult to grasp precisely the extent to which he may have meant this metaphorically, but the sense is that, as always, he is at least glancing off literalism, because the imaginary is all that remains of the real. If only in some respects, reality is an imaginative construct. If you are able to persuade the majority that what is real is the way you describe it, you are halfway there. If you can furthermore construct the semblance of that reality, like a stage set, across the line of vision of the population, what is left to contradict your account of what reality is?

Under the attrition of the conditions Baudrillard intuited in the world as he read it, everything turns into a movie. Because everyone is nowadays conditioned to think of unfolding reality in this way, it is not difficult for would-be manipulators to impose themselves and their plans for the world. Accustomed to following three-act narratives, the people respond as though naturally to scripted versions of ‘reality’ — pseudo-realities, the new commodity of media.

Moreover, the tenor of events conveyed via technologies has become such as to create doubts as to whether this content is even remotely credible, since the technical possibilities and the quasi-perfection of the delivery is such as to bring into question the existence of a source event — something humanly-generated behind the commodity that plops fully formed into my Inbox, for example — just as the perfection of stereophonic sound casts doubt that the music could have originated from an organic orchestra or performer. Since we cannot return to verify the source, we are cast into a netherworld between doubt and certitude, neither believing nor disbelieving, lacking either faith or scepticism. Baudrillard described this phenomena decades before the onset of deepfakes.

Oh right!, you may pipe up again, ‘It’s the Matrix’. Yes, but be careful!: Baudrillard also precedes the Matrix in all its incarnations. He is the father and Godfather of The Matrix. His work it was that inspired the movies of that name, but, although involved at an early stage as an adviser, he later disowned the project as having departed from his intentions.

He did not foresee the total implications, however. As a metaphysical anarchist (though not a nihilist or an amoralist), he did not see any of this as necessarily representing a catastrophe. In a passage about the modern ‘subject’ in his book Impossible Exchange, he speaks — ironically, one hopes, but perhaps not — of the ‘liberation' of the subject through technologies, networks, screens, causing him to become fractured, ‘both subdivisible to infinity and indivisible, closed on himself and doomed to endless identity.’

If one wished to be prosaic and old-fashioned — i.e. working by the logic and methods of the departed world of ‘reality’ — one might plunge in and divine a series of ‘sociological’ explanations for the things he claims for the simulacrum and how things have played out since his death in 2007. You might say, for example, that among the effects of the past and future waves of technologisation is indeed, as he says, a form of ‘liberation’, but that the ‘liberation’ in question is one that tends towards chaos and disorder, and therefore may be the opposite of freedom. But why, how? Perhaps because that is the nature of power, of whatever form; perhaps because the nature of culture is to abhor a vacuum; perhaps because, in removing the children earlier from the supervision of their parents, popular technology renders them culturally feral — in a certain sense ‘smarter’ than their parents about things that matter only in the simulacrum, but which in time become the only things that matter to them — and therefore prone to de-civilising tendencies.

This sense of ‘liberation’ transmits itself through the culture, licensing changed behaviour by everyone implicated, so that soon, only the hermit is left unaffected. At its core, the ‘liberation’ spoken of by Baudrillard had to do with the insinuated notion that the past had ended, history had ended, and therefore virtually — so to speak — everything that had mattered before no longer did, or mattered a great deal less than it had. The effect on the young afflicts the thinking and behaviour of parents, who also happen to be the lawmakers, judges, police officers, doctors and TV presenters. In general, these — though still recognisable as figures of authority — had long since sought the elusive quality of ‘cool’ on account of the inward pressure of the post-1960s culture, and so were rather easily persuaded. In as far as what has occurred can be communicated sociologically, this is about as much as needs to be said. Baudrillard barely, if ever, addressed these circumstances in sociological terms, but spoke always as though of a form of magic, probably because he knew that this was the way the effects and consequences were going to manifest in the world. What he did not so much predict was that it was going to be overwhelmingly a black magic, at least as it proceeded. Up to the time of his death in 2007, the effects seemed to be precisely as he had predicted them; it is only in the past decade or so that the toxic, destructive nature of these phenomena has become clear.

So: At some uncertain point of rupture in the not-too-distant past, man ceased to live in reality but moved unknowingly, as though sucked into a black hole, a ‘simulacrum’ of the real — and yet lacking all but the most superficial similarities to it — a virtual world made of circuits and networks and pixels and memes, in which it was necessary for man to virtualise himself so as to cease to be a subject in the old sense with an ‘I' and a soul, and become as a unit of the crowd. The ‘perfect' subject of the simulacrum, Baudrillard writes, is an individual who has also a mass status — as a particle of the mob outside his window. He is ‘the dispersal of the mass effect into each individual parcel . . . Or, alternatively, the individual himself forms a mass — the mass structure being present, as in a hologram, in each individual fragment. In the virtual and media worlds, the mass and the individual are merely electronic extensions of one another.’

Again, we may try to translate: ‘Ah, The crowd! Mass formation.’ Yes, of course — but . . . ‘

Man fragments into many and becomes a crowd, which in turn becomes as though an individual mind. This is somewhat close to the characterisations of Gustave Le Bon, almost a full century before Baudrillard. But Baudrillard proposes an additional possibility: Technology creates a fragmentation that (simultaneously?) afflicts both the crowd and the individual, as though the quantum structure — which previously defined the individual only — has somehow become an equally functional description of the crowd. The individual no longer exists, though the presumption of his existence persists, because he leaves footprints and seems to be standing there. But in ‘reality’, according to Baudrillard, there is no one there. Now there are only crowds, but for the moment the constituent ‘elements’ (humans) presume themselves to be as they were: separate and independent.

All this happens at the level of apprehension by the imagination, which is really the only reality we can know. What is real is what is capable of being imagined, and this is more concrete than what is true, or concrete. Baudrillard draws distinctions between ‘reality’ (what has disappeared) and ‘the real’, which replaces it.

A simulacrum is not the same as a fake. The simulacrum is hyper-real, which is to say it is realer than reality, which is abolished in the process of the simulacrum’s creation. It is, says Baudrillard, ‘the generation by models of a real without origin or reality’. It is the map without a territory; the map is all there is, the territory may as well never have existed before the map, and probably didn’t — ‘and nor does it survive it’. The map precedes the territory, which is abolished. We live in the map, imagining it is reality, whereas there is no longer a reality and only the map is real. The simulacrum is a space in which there is no difference between ‘true’ and ‘false’, or between ‘the real’ and ‘the imaginary’. There is no difference between a person simulating insanity and an insane person, and, by the same token, no difference between a politician stating something he claims to be true and a politician telling the truth, for once he has stated it, it becomes true.

The real has been replaced by the signs of the real, which are more convincing than the real, on account of there no longer being any distinction between the real and the imaginary. This presents a strange involution of thinking: It is implicit in everything Baudrillard writes on this subject that he is addressing the condition of culture, and it is in this sense that he seeks to parse the meanings of ‘reality’, ‘the real’, the ‘fake’ and ‘the simulacrum’. Culture is the only real phenomenon, because what we believe becomes what we know, which becomes the only truth that counts. Whatever emerges from this cultural schemozzle will be all the reality we can know. Thus, when Baudrillard speaks of the conflation of ‘the real’ and ‘the imaginary’, he is defining the precise nature of the role of the imagination — collective and individual (insofar as this remains relevant) — of humanity, and in doing so saying that what we imagine, or are brought to imagining, will be the reality that imprisons us. Just as there is no difference in ‘reality’ between ’the real’ and ‘the imaginary’, so too with Baudrillard’s hypothesis, which concerns the imagination but in doing so defines the (new) ‘real’. The only evidence of ‘the real’ is in what we imagine for ourselves about what reality is, which has ipso facto become the sole actually existing reality.

This (new) ‘reality’ emerges, as though spontaneously, from the viscera of postmodernity. The ‘real’, says Baudrillard, is produced ‘from miniaturized cells, matrices, and memory bands, models of control — and it can be produced an indefinite number of times from these. It no longer needs to be rational, because it no longer measures itself against either an ideal or negative instance. It is no longer anything but operational.’

This observation contains enormous resonances for what has happened to politics, government and the rule of law in our countries in recent years, but especially in the past 40 months.

Baudrillard’s essential thesis centres on the idea that the effects of technological and communicational developments had been such as to move the function of mass media from tracking, or — more often — concealing reality, to actually generating reality. This is what he refers to as ‘simulation’, a process of constant reproducing of reality out of the signs, codes and models of media, filtering in turn the signs, codes and models of politics, ideology, science, medicine, et cetera. This has been achieved mainly through the use of digital technologies, whose binary nature serves to subdivide the world (i.e., mostly its population) into two essential elements: (my speculation: originals and copies, thinkers and repeaters, purebloods and cyborgs, et cetera). These processes he saw as forms of forgery, mirroring those of medieval monks copying texts from ancient manuscripts, the mass production processes that followed from Frederick Taylor’s streamlining of the production line, Andy Warhol’s work with repetitive multiples of iconic images, and modern devices like the camera, the photocopier and the scanner — and, of course, the internet.

Baudrillard’s chief preoccupation is with considering the effects of these processes on the subjectivity of the individual. The shift from object to image (i.e. a visual recording of an object or person) changed the human perception of reality. This, he argued, was moving us out of reality, in which everything was as it appeared, into hyperreality, in which everything was whatever we imagined it to be. Hyperreality is the world of the viral, the fractal, the exponential and the metastatic, an infinitely dividable reality in which reason and comprehension depend on managing the speed at which the material of reality shifts — i.e. a coping with constant chaos and change, with an endlessly repeated reissuing of images and facts, in which instability is the natural order and for which the generation of cancerous cells within the human body presents the most appropriate metaphor. In this, writing up to half a century ago, Baudrillard anticipated the algorithm and the neural network, which today evince the impression of being no more than the vindication of his theory: programmed mechanisms capable of simulating intelligence, cognition and even sentience, but which remake reality moment-to-moment according to formulae that even those human agents that create them are unable to predict as to their logics, actions or effects.

Here we come to Baudrillard’s insistence that all this can alter not merely facts but ethics and reason as well. The problem here is that, although the machine may be designed by a human intelligence, the ‘magic’ of the algorithm may confer capacities greater than the sum of the inputs. If the programmer primes the machine with an ‘ethical’ programme, and adds in a number of layers of additional coding, ascribing weightings to various moral and ethical factors, the programme enables the machine, on the basis of an instantaneous scrutiny of comparative data, to ‘think’ about situations that had not occurred to the programmer, perhaps because they were not yet even possibilities at the time of installing the programme. The impenetrable, indivisible algorithm has already ushered in an undeclared era of hermetically-sealed, instant decision-making, in which the outcomes of life-changing human decisions may be decided by software that writes itself and algorithms with the capacity to outgrow the intelligence of their creators. These processes can only take forms that are arbitrary and summary, which means that the future cannot possibly be otherwise. The even stranger thing is that, even in advance of the algorithm gaining a total hold on human culture in this way, many of the human actors governing our societies and their cultures appeared to ape these tendencies without ever having observed them in action. Hence, the lying automaton of the Covid era who claims to be ‘saving lives’ while ordering the mass slaughter of the elderly to maintain an adequate level of scare porn; the pathocratic politician who evinces ‘compassion’ for fraudulent migrants while destroying the hopes of his own people; the journaliar who had misled his audience for 40 months appearing at a public demonstration about media salaries with a placard declaring that ‘Truth matters’.

Baudrillard says: ’The universe of simulation is transreal and transfinite: no test of reality will come to put an end to it — except the total collapse and slippage of the terrain, which remains our most foolish hope.’

In the hyper-real world, all shade and subtlety are lost, because the binary is the sole measure of distinction and definition. The ‘real’ is merely a series of ones and zeros. Even God can be simulated, and this means that the world is no longer a world created by God, but by those capable of simulating God. This involution is the core of what is happening to us now. In a world after God, all things are permissible.

Baudrillard is sometimes dismissed as a fake philosopher who creates webs of words that mean little or nothing. But the test is whether what he says makes us feel a correspondence with what we experience more compelling than any of the ‘rational’ explanations, and he passes this test every time — and with colours that fly better with every passing day. Perhaps he is not really a philosopher at all — but rather a seer into the meanings of things. But what’s the difference, since most ‘real’ philosophers have already vacated both the territory and the map?

I would say that Baudrillard is the first and most comprehensive prophet of totally secularised reality, in the sense that he has announced the core meaning of a world not created by God. This is not to suggest that God did not create the world — for the purposes of this analysis, that questions remains an open one — but Baudrillard announces a world in which God’s intentions, laws, even His materials, have been usurped and superseded by a world in which man has become . . . not the god he imagines, but a highly proficient forger of reality, whose reign must be acknowledged and accepted until it comes to triumph or, more likely, grief.

In a 1995 essay, The Double Extermination, (about the WWII Holocaust, but this is not the immediate resonance that interest me), Baudrillard spoke of the delusional nature of mankind’s sense of its own relationships with the virtual, which is presumed to be some kind of tool to extend human power over reality, but (in reality) is something altogether else.

Today we do not think the virtual, the virtual thinks us. And to us this elusive transparency, which separates us definitively from the real, is as unintelligible as is the window pane to the fly which bangs against it without understanding what separates it from the outside world. The fly cannot even imagine what is setting this limit on its space. Similarly, we cannot even imagine how much the virtual — as though running ahead of us — has already transformed all the representations we have of the world. We cannot imagine this, for it is the particularity of the virtual that it puts an end not just to reality, but to the imagining of the real, the political and the social; not just to the reality of time, but to the imagining of the past and the future (this is what is known, in a kind of black humour, as ‘real time’). So we are far from having understood that information's entry on the scene spelt an end to the unfolding of history, that the coming of artificial intelligence spelt an end to thought, etc. The illusion we still harbour about all these traditional categories — including our illusion of ‘opening ourselves up to the virtual’, as if it were a real extension of all potentialities — is the illusion of the fly unflaggingly banging up against the window pane. For we still believe in the reality of the virtual, whereas the virtual has already virtually scrambled all the pathways of thought.

Later in the same essay, he re-emphasises the extent to which everything — politics, sociology, history, thought — have become virtualised:

The social, the political, the historical — even the moral and psychological — there are no longer any but virtual events within all these categories. This means it is useless searching for a politics of the virtual, an ethics of the virtual, etc. since it is politics itself which is becoming virtual, ethics itself which has become virtual, in the sense that both politics and ethics are losing the principles governing their action, losing their force of reality. And this even applies where technology is concerned: we speak of ‘technologies of the virtual', but the truth is that there are now only — or there will soon only be — virtual technologies. Now, there can no longer be any notion of artifice in a world in which thought itself, intelligence, is becoming artificial. It is in this sense that we can say that it is the Virtual which thinks us, not the other way around.

This implies that such as politics and ethics are things of a past that becomes a receding and beguiling memory, which would go some way to ‘explaining’ some of the things we have been witnessing for the past 40-odd months: the sudden break into amorality by politicians, the silent abolition of nations and laws, the tyrannification of police forces, the outright corruption of judiciaries, the flipping of media models from approximate truth-telling to outright and ceaseless lying. And, here in what passes for a present, just as the 1970 Ford Escort seems simultaneously to resemble both a spaceship and a gangling jalopy when parked in a contemporary streetscape, and looks like it was designed to look like some kind of defiant response to a 1960s Ford Prefect or Popular, so the value system of the emerging reality is being formulated as the antithesis of what came before. In this dispensation, good becomes bad; bad, good; pervert, paragon; up, down; in, out; truth, lie; liar, fact-checker. This is why things feel so weird, why words have run out of road. We move in a new world, while imagining we live in a continuum from the old.

Such insight into reality may remain elusive for many because the new constructs sprout as though organically from older, more stable ones, inheriting and adopting the modes and codes of these to an extent that enables them to pass for naturalistic continuations into a new era that promises only good things. The habits of existence in linear time have insinuated a continuous plausibility that survives the most radical alterations of direction and character, and somehow, in the imagination of a majority, the transition is unnoticed. Standing on the foundations of the old model, the present edifices appear as simply modernised version of the same basic idea as before, whereas they are in fact, something utterly novel, without precedent, good or bad of it. Edifices of trust constructed multiple generations ago, and handed down with joy and pride, have been inherited by inhabitants of an entirely different world, in which the operational ‘ethic’ is to bleed everything for instant profit and to regard human beings as a superfluous irritant, unless they are immediately useful, which mostly they are not. Moreover, our habits of associating concepts, by way of analogy, with the material world continues to beguile us into waiting for this (new) world to stabilise itself according to the old (immutable?) rules.

There is also, Baudrillard warns, something dangerously therapeutic about this new world. Andy Warhol remarked that ‘the more you look at the same exact thing . . . the better and emptier you feel’. He was referring to the repetitious nature of popular culture, which he leveraged for the purposes of both commentary and exploitation. His belief about the emotional benefits of repeated viewing led him to repeat images in his own artworks. We look upon his Marilyn Monroes and instantly feel that they are ‘iconic’ of a time when repetition was a virtue, perhaps the only one. Now, we live in an incomprehensible world in which the familiarity bred by repetition of half-remembered sensations is the only thing that gives us peace.

Warning: This may be the first of a two-part series. Watch out!.