The Abolition of Reality, Part II

‘Through an unforeseen turn of events . . . it is from the death of the social that socialism will emerge, as it is from the death of God that religions emerge.’ — Jean Baudrillard

This post may be too long for the Substack newsletter format. If you’re reading it as an email and it tails off unexpectedly, please click on the headline at the top of the page to be taken to the full post at Substack.

Kinky Totalitarianism

The ‘liberation of the networks’ to which Jean Baudrillard referred is not a technical freedom. The technological aspects are not disputed, but are a given, baked (or fried) into the combination of capacitors, microchips, motherboard, processing unit, hard-disk, pendrive, software, and random access memory, otherwise RAM, that constitute the ‘computer’. An equally critical element of computer systems, all the gearheads seem to agree, is the ‘liveware’, which includes the programmers and systems analysts, but also the ‘end users’, who engage and interact with the computer to give it its life and content. It is the end-user liveware who experience the ‘freedom’ offered by the networks.

It is not, by definition, an analogue freedom, and this may offer us a clue as to how the meaning of freedom became distorted to the extent that people calling themselves ‘liberals’ no longer regard it as a vital quantity, while the words to describe it remain unmodified and in use. The ‘liberation of the networks’ is neither existential nor metaphysical, at least not in the old sense. It is not a freedom of the spirit, but of the emotions and the instincts. It is the freedom of the addict, not of the questioner or investigator. It is the freedom to be free, on the terms of a ring-fenced ideology, rather than the freedom to simply be. In other words, it is a freedom of concepts and sensations, rather than of the imagination — of the gut and below, rather than the heart and above. Its cardinal quality is of a particular category that might be defined as ‘freedom to enjoy’, or ‘freedom of the flesh’, ’freedom of the impermissible’, freedom to fulminate, to pontificate, to trumpet, to rant. It is a freedom that trashes commandments as the arbitrary impositions of the bearded old, destroys taboos without asking why they arose, and removes the intimate from the private realm and places it in the public square. In this liberation, the pubic becomes public, and becomes amplified beyond prudery or shame by the networks, which neither exhibit nor tolerate either quality, and announce this disavowal with pride.

What this artfully excludes is the core of freedom, previously understood, albeit implicitly — unspokenly — as the freedom to proceed through reality unimpeded — by one’s own lights, but also on the path suggested by the facts and circumstances. This is the freedom to ‘be’ in ‘the world’, to move, to explore, to advance, to aspire, to attain, to yearn — and yet to hold all these impulses in abeyance in the knowledge that no such trajectory is capable of achieving total correspondence with the propelling drive or desire. What the liberation of the networks is not is freedom to proceed, in any direction, towards the horizon, as the intuited destination-point of the human journey, this being the most fundamental, nomadic instinct of the human person — to walk purposefully towards the skyline with a light regard for wherever one passes through, always conscious that the driving disposition of the human is to move through this dimension on the way to some indeterminate place, which may be named or unnamed, but is either way unknowable. This is, at its core, the meaning of religious experience: the creation of an imaginative accompaniment to the journeying of the subject in ‘moving through’ reality in a manner that defines the optimal demeanour of the human, on the way to another, intuited, imagined, place.

It is striking that, in the lockdown of 2020, what was targeted was not the freedom to, for example, fornicate, even though that might have been deemed a likely source of transmission, or the right to abort an inconvenient child, or even the right to riot (provided that the rioting was directed at targets other than the Regime), but the right to proceed. more than a specific distance. It was as though each citizen had been shackled to a particular point in the world — usually his home — by a chain of, depending on the jurisdiction, 2 kilometres in length, or 5, so as to — as though precisely — prevent him from advancing towards the horizon.

If there is a single factor that defines and explains the shift that has occurred in the world, it is the adoption of network freedom as the only true kind, and the downgrading of the ‘freedom to advance across reality’ to the point where mention of it provokes only puzzlement. And, in the absence of this understanding of human existence, reality itself has disappeared and being replaced by a counterfeit. This, essentially, is what I take from Baudrillard’s ‘simulacrum’.

The liberation of the networks is crude, indulgent, unrestrained, grotesque, gross, lewd. It bears no resemblance to technology, and yet, as Baudrillard comprehended, is indissolubly married to it. It is a purging of everything inherited, a colossal incontinence that takes the greatest pride in its dissoluteness. It represents the inversion of transcendence and the obliteration of the metaphysical. It is the embracing of chaos to the point where the New World Order that it signifies ought properly be called the New World Disorder.

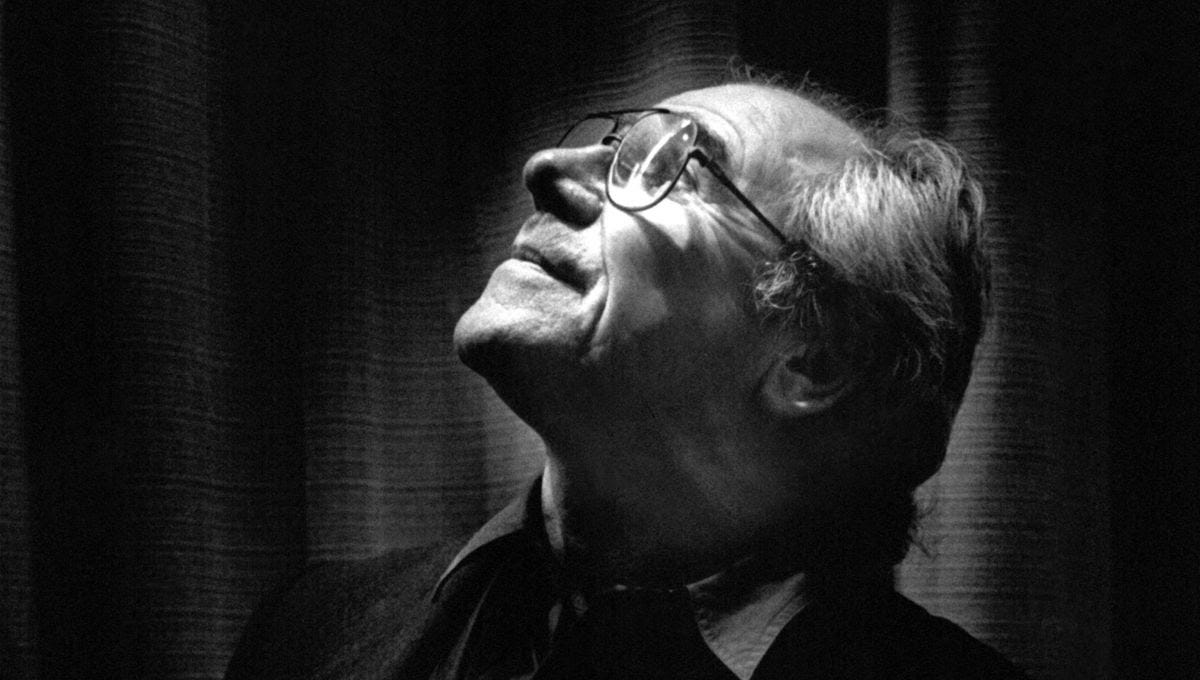

Perhaps, if he were still with us, Baudrillard might at this stage, as was his wont, inform me that what I describe is not synonymous with his thesis. Not only would I have to accept this correction, but would do so gladly, for I am not sure that even Baudrillard understood his own hypothesis, and being permitted to ‘borrow’ his hypothesis for these articles, regardless of their grasp of his ideas, is extremely invaluable in communicating the otherwise inexplicable. Even if I misunderstand him, that misunderstanding is transcended by the fact that what I divine from his words appears to provide a map for the present in ways that I do not believe he anticipated.

As I said in Part I, I don’t take Baudrillard literally, in that I do not imagine that he is talking about some kind of deliberately constructed — silicon brick by silicon brick — digital prison. I think he is talking in parables, in which he is saying that the effects that he appears to describe us as experiencing are ‘like’ this or ‘like’ that’. I believe he is silently saying, almost before every sentence, ‘It is as though . . . ‘

In a sense, then, his concept of the simulacrum is more of a simile than a metaphor. He is not talking about the conventional idea of a ‘simulation’ — a computer-generated illusory universe in which we exist only as holograms. I shy away from the idea that he is talking about a world resulting from an alien experiment, or a teleported construction of future humanoids, sent spinning backwards through time; or some kind of quantum coup driven from CERN, or someplace; or some cosmic silicon-heavy giant sitting in dark space in his underpants, trying to decide if he’ll wipe me out with a spot of quantum retro causality magic, or just have me run over by a bus. I believe, as I said in Part I, that Baudrillard, a poet above all else, is talking about culture in the only way he can manage to explain its behaviours as he sees them. In a way, I believe, his hypothesis is akin to the way that I have come to see the possibility of what I fear will become indistinguishable from ‘intelligent’ or ‘sensate’ algorithms: I do not literally believe that it is possible for a computer to become sensate or conscious or ‘more intelligent than humans’, but I do believe an algorithm or neural network is capable of being programmed with behavioural intelligence and multiple-layered data to render it capable of replicating the condition of an intelligent or sensate being in a manner that might be impossible to distinguish from an actual such human. As with this hypothesis, Baudrillard’s simulacrum evolves not in the manner of a biological organism, but in the processing of information in such a way that the computational outcomes look cannily organic. I don’t see this as a ‘simulation’. I think I am closer to Thomas Sheridan’s idea of the Vedic concept of the ‘maya’ — a ‘consensus illusion’ that we all share, except that I would say we do not so much create the phenomenal world as an illusion but that we render it ‘real’ by virtue of our consensual observation and description of what we ‘perceive’. I think there may be some elements of this in Baudrillard’s thinking, although he strikes me as an implacable atheistic sceptic of supernatural notions of transcendence. In this context, his ‘simulacrum’ is an altered perception of reality, and accordingly a de facto altered reality, which (I’m guessing) most likely erupted out of 1960s notions of freedom, and was amplified and accelerated by the explosion of popular tech from the late 1990s onwards. There is, therefore, in the simulacrum, an insinuation of cultural forces meeting technological forces to create something not self-evidently implicit in either. Humanity has control of the simulacrum in a cultural sense only, which is to say that it can adjust the simulacrum through cultural initiatives and modifications or reinventions of tech forms. There are no ‘controls’ other than the process of human existence and being, and those governing amplification and acceleration. We can ‘re-simulate’ by acts of cultural intervention, psychic overtures, and possibly even some forms of spells. But mostly our interventions take the more modest, prosaic forms of the kinds of attacks on human consciousness represented by a novel, a movie, a poem, an essay, or even an article or interview.

In this sense, the conditions I seek to nail in this essay is not especially esoteric, and certainly not in the realm of woo. I seek to forge sentences that might resonate with the way others may be experiencing the things I see and feel. What confronts us is a culture that has altered radically under the attrition of ideological clamouring and wholesale misuses of power — including celebrity power, banking power, judicial power, media power, with political power merely following what appeared to be a winning programme. To a high degree, what we seem to be talking about here is the expedited construction or reconstruction, in a matter of weeks or months, of cultural edifices that might normally take decades or even centuries to build or remodel. In some respects, the simulacrum is useful only up to a point in explicating this phenomenon, which, as I keep saying, is overwhelmingly cultural in the manner in which it makes landfall on our awareness. What I seek to articulate is really a way of obtaining emotional traction in reality at the level of imagination, rather than engagement with concrete, physical, material reality, which is how we have mostly been prone to think about questions of changing reality hitherto.

An equally useful but limited metaphor might be that of ‘The Longhouse’, a concept I confess I first encountered in an article last February on the First Things website, written by the strangely-named L0m3z.

The article has been among the online edition of the magazine’s ’most read’ for the past six months, something that, as far as I know, is unprecedented, as articles normally fade away in a couple of weeks. I can see why: The article, though it leaves much unexplained or unelaborated, is fascinating. Rereading it again recently, I was struck by the idea that, from another angle, it contains many of the elements arising from the current ‘Situation’ that I am identifying in Baudrillard’s simulacrum.

ChatGPT tells me that The Longhouse is:

a traditional style of dwelling historically used by various indigenous peoples, particularly those of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) and other Native American tribes in North America. It is a long and narrow building made of wood and covered with bark or thatch. Longhouses were communal living spaces, accommodating extended families or multiple families within the same structure. These structures played a significant role in their culture and social life, serving as homes, meeting places, and centers for community activities.

L0m3z asserts that The Longhouse was not a dwelling place, but more of a gathering space for a tribe in which it ventilates matters of concern and tries to resolve disputes by consensus. It seems to have functioned a little like a church — a linear, long, narrow building — and yet was not a religious building, more a town hall or a substitute for what, in modern society, became the role of the café. To an extent, the concept appears to collapse the distinction we have had in Western societies, whereby the temple/church was the sole building in the village/city you might enter without ‘permission’, and yet was a separate and quite different place to the home. Each Longhouse was different to all others, reflecting the unique sensibilities and characteristics of a particular tribe, family or community. It represented a worldview and way of life, a spirituality, a connectedness with nature and the infinite/eternal, but also a way of seeing the world outside the family, community or tribe. The Longhouse was the focal point of the pre-colonial tribal world, and was to be found in cultures as diverse as those of the American Indians and in countries including Afghanistan, Japan. India, Burma, Thailand, and Cambodia. The most notable examples are those built by cultures such as the Iban in Borneo, the Gogodala in New Guinea, the Vikings in Norway and Denmark and the Iroquois in the American Midwest.

I am open to the idea that what I seek to pursue in these articles is at least partially accessible by this avenue also. Perhaps what I have in mind, though triggered by Baudrillard’s characterisations of the atmosphere of his simulacrum, is an ideological simulacrum, a governing programme of ideas or thoughts that might furnish the ‘Longhouse’ of a society in a manner that suggests continuity while representing rupture.

L0m3z, adapting the concept to the modern moment, elaborates:

Maybe this term means nothing to you. Even for those of us who use it, the Longhouse evades easy summary. Ambivalent to its core, the term is at once politically earnest and the punchline to an elaborate in-joke; its definition must remain elastic, lest it lose its power to lampoon the vast constellation of social forces it reviles. It refers at once to our increasingly degraded mode of technocratic governance; but also to wokeness, to the ‘progressive,’ ‘liberal,’ and ‘secular’ values that pervade all major institutions. More fundamentally, the Longhouse is a metonym for the disequilibrium afflicting the contemporary social imaginary.

The author sees the concept historically in a frame much wider than that supplied by ChatGPT — as a building only in metaphorical sense, but moreso as a cultural storehouse of values of ‘peoples throughout the world that were typically more sedentary and agrarian.’ The household was a corporate group and the Longhouse was a home, a kind of parliament, a court and an office of social organisation. It was here that the tribe resolved disputes in which individual autonomy came in conflict with collective identity.

Really, the term ‘Longhouse’ refers to the locus of a community possessed of common ideals and objectives, seeking to live together on the basis of consensus. In a ‘modern’ society, the term might be used — and L0m3z uses it — to describe a nation being carried along by a virtually coercive ‘belief’ system imposed by majority rule or propaganda or tacit state diktats. In the old Longhouse, members could ‘vote with their feet’ — i.e. leave to join another community. Thus, while the article is interesting, it is by no means a perfect analogy. Although I am not sure how much of L0m3z’s thesis is original to him, or whether this concept has already been adapted to the modern context, the hypothesis offered by the First Things article, though intriguing and compelling, seems also somewhat stretched, though perhaps no more than my own use of Baudrillard’s simulacrum. And yet it is extremely interesting and relevant.

In our ‘modern’ context, the author asserts:

More than anything, the Longhouse refers to the remarkable overcorrection of the last two generations toward social norms centering feminine needs and feminine methods for controlling, directing, and modeling behavior. Many from left, right, and center have made note of this shift. In 2010, Hanna Rosin announced ‘The End of Men.’ Hillary Clinton made it a slogan of her 2016 campaign: ‘The future is female.’ She was correct.

It is clear already that the L0m3z thesis is a great deal removed from that of Baudrillard, and yet it outlines some elements that might be inserted without difficulty into the simulacrum hypothesis. The modern American Longhouse (contrary to the incessant discourse implying continuing discrimination and inequality) is dominated by women, and female thinking. The same is true for all European societies, certainly the Western parts. This implies a profound, unacknowledged change of culture and values. It means that, for example, principles of justice have been altered in their very fundamentals, and not in the ways that were comprehensively anticipated. From this new culture has emerged concepts like political correctness, victimology, affirmative action, trigger warnings, ‘protected characteristics’, cancel culture, the shift from reason to feelings, Safetyism, the ‘Karen’ phenomenon, and so forth. The modern Longhouse is ruled by The Omnipotent Victim, and this has made all but inevitable the ’success’ of, for example, the Covid coup, which pivoted on the notion of risk avoidance, a maternal quality and preoccupation.

L0m3z continues:

The implications of the Longhouse reach yet further across the social landscape. The Longhouse distrusts overt ambition. It censures the drive to assert oneself on the world, to strike out for conquest and expansion. Male competition and the hierarchies that drive it are unwelcome. Even constructive expressions of these instincts are deemed toxic, patriarchal, or even racist. [. . .] It is the same for the arts. Woke obsession with diversity and inclusion, the rise of ‘sensitivity readers,’ and racial quotas in film, overshadows the equally insidious fact that so much of what passes for ‘high’ culture has devolved into dreary, toothless portrayals of static lives. There is a failure of imagination on all sides. The right's retreat into the classics, while edifying, will not supply the modern symbols and narratives necessary to guide us out of the Longhouse.

L0m3z concludes:

[W]e must resist the soft authoritarianism of the Longhouse's weepy moralism. We must not succumb to hysterical pleas for more safety, more consensus, more sensitivity. Ennobling work awaits us. But we must first recognize the Longhouse for what it is and be willing to leave its false comforts behind.

Something highly germane to all this that L0m3z does not consider is that these may not be organic processes, but orchestrated initiatives calculated to exert immense and radical pressures upon the world and its population, and achieve unprecedented changes that together are as far from liberation, and the associated ideals of democracy, that can be imagined. In other words, what confronts us is not at all — at least not in its conception — the fruits of agitation for equality, but of hidden expressions of power that most of the human population have never countenanced as even existing. For that matter, neither did Baudrillard appear to detect the presence of a watchful, conspiratorial force in the world, a force that, for perhaps decades if not centuries, had been feeding certain stimuli into the cultures of the more advanced societies, which, in the increasingly mass media saturated world, was by the change of the millennium amounting to almost the entire globe. It is understandable: He did not want either to enter into the world of the prosaic, to become embroiled in facts that, by their nature, would make his hypothesis an ugly or convoluted one. Yet, for us it is important to understanding: From this malevolent source of manipulation came the material out of which the new world would be forged — sexual freedom, rights specific to minorities, climate change, critical race theory, et cetera. As the manifestations of these phenomena began to ramp themselves up, the political class, having already forfeited all power, jumped immediately to cling to the back of the bandwagon.

The Longhouse, no more than the simulacrum, is not a perfect instrument or motif, but, in considering the forces that have overcome our nations in the past 40 months, it is helpful to have in mind some definite location in which ‘culture happens’, even, as here, a quasi-metaphorical place functioning as both temple and house, where the public and the private might happen as though inextricable, one from the other. Though the traditional longhouse was spiritual (not religious per se) the modern one is predominantly sensual/sexual in that it leverages physical desire as the ultimate human satisfaction and destination.

Now, in our societies, in the place where ‘culture happens’ — no matter how we may seek to describe or define it — very strange and unprecedented things are happening. One could start almost anywhere, but let’s start with politics, the organising system of our cultures, and consider what has happened to the process of representation.

Baudrillard, writing in 2001, spoke of a ‘silent insurrection’ in modern society, among the symptoms of which he identified ‘a refusal to be represented’ (he meant politically). He had in mind a refusal arising from the technologisation of modern life and the consequent alienation of the human person from a sociological reality that, in the simulacrum, rings ever falser. Some two decades later, his analysis reveals itself as prophecy. Caught between the real and the virtual, the modern inhabitant of cyberspace is no longer representable in the old way. Politics and the freedom offered by democracy have revealed themselves, in this diagnosis, as ‘bit-part playing and a shabby hoax’, for many cyber-savvy young people a ‘doltish activity’ in which they have no interest. The liberation of the networks is a better bet.

More alarmingly, Baudrillard talked about a strain of humanity that had moved beyond freedom, meaning and even identity, where human beings become as subjects of a new order who may use the language of politics but no longer recognise its purpose or usefulness in their lives. Ideas like ‘running the country’ or ‘envisioning the future’ are alien to them, because they believe that, like their iPhones and laptops, ‘the country' is somehow looked after, or looks after itself, and the future will be there waiting for them when they get there. They seem to envisage a democracy run along the same lines as a Google search: a random series of benefits tailormade to their needs and delivered like baguettes hanging on their door knockers when they awake from their dreams or nightmares. ‘What interest,’ asks Baudrillard, ‘does the modern individual have in being represented — the individual of the networks and the virtual, the multifocal individual of the operational sphere? He does his business, and that is that.’

Sure enough, the young as we encounter them in our families and neighbourhoods seem to be unreachable, mainly because they no longer live in the ‘real’ world, but as though in a form of Baudrillardian simulacrum, in which technological values rule and the main obsession is creating and defending your 'identity' so you can keep on killing rather than getting killed.

Once, teenage boys collected election leaflets in the manner of football cards, but nowadays most people under 40 could scarcely tell you the name of their Minister for Justice. They don’t care. And yet, as though paradoxically, they will acquiesce in some particular abuse or injustice conducted by the same Minister for Justice, provided that her reasoning is rooted not in history or legal jargon, but in the ideological sci-fi world they imagine themselves to inhabit in the present, and so long as she delivers her diktats while dressed in rainbow colours and appropriately-sculpted shades.

There is something strange here, something that erupted in plain sight in the middle of 2020 in the demeanour of many young people towards the tyranny of lockdown and its sundry associated ‘mandates’: Not only did they not seem to object, but they even seemed to like it. Further observation of the responses of the young to the machinations and demeanours of such as Macron, Trudeau, Varadkar, Ardern and Sturgeon suggested something new and freaky: Today’s voters might be open to entering into a kind of sado-masochistic relationship with their rulers provided they are allowed to think of it as just a game and are never bored. The pain they ‘enjoy’ is not of the physical kind, but relates to the idea of being dominated by a figure evincing some form of perverted sexual energy, a form of punitive domination combined with what was almost a form of ‘cuckolding’ in respect of their hitherto inalienable right to freedom.

Things that seem to bore the young include: historical facts, economic theories, arcane explanations for why things are as they are, and justifications for action rooted in constitutional jargon, rather than ‘compassionate’ ideological language. Constitutions mean about as much to such beings as rolls of kitchen towel. History is too complex and complicated and . . . boring. Economics is incomprehensible, and pointless. Immunology might as well be Double Dutch. If it seems weird to be leaving these subjects to the kinds of people who generally tend to ‘go into’ politics, then consider the question as to whom else, in the modern world, might they be ‘left to’. In a world where ‘expertise’ is increasingly fragmented between ever-shrinking and unconnected disciplines, only the politician is ‘qualified’ (by being there, occupying an ancient, elevated position that no longer has power) to speak across the disciplines, make a definitive statement and announce a remedy by way of decision which becomes mandatory by default. A strange paradox of the modern disposition towards politicians is that, in a time when they have been stripped of all authority and power, and are loathed and despised in a manner never before experienced, they have become more and more like a secular, if not an occult, priesthood of science. Paradoxically, the young dislike their politicians while finding it easy to ‘love’ them (in the ‘loving Big Brother’ sense), to submit to them, to be their slaves and bitches. This is due to a little-remarked element in the ether of public culture today, that was not there before: a latent frisson of only slightly repressed sexual perversion, mainly arising from the sexual fixation of modern ideologies, the levels of pornography that have been just a click away from ‘reality’ for more than two decades, and the absence, since the abolition of God, of a more fundamental focus of desire. This aspect has been amplified by the presence of more and more women in positions of power— often quite unpleasant women, like Jacinda Ardern and Nicola Sturgeon and Ursula von der Leyen. Today’s electorates may not admire or respect their politicians, but they relish them almost in the roles of kinky gaolers, who implement their ideological choices while simultaneously exercising the whip hand. Totalitarianism, couched in the demeanour of BDSM, reveals itself as an acceptable mode of tyranny, because it has the appearance of consensual role-playing while being driven by a deeply resolute purpose, which in turn accentuates the ‘appeal’. That it is, in almost every conceivable sense, a playing of roles does nothing to mitigate the risk of misadventure, since in the ‘game’ being played there are no limits or safe-words. In truth, the function of the media as destroyers of meaning (see below) ensures that the absence of reality or realism makes this circumstance even more fraught than either a genuine tyranny or a ‘genuine’ role-play.

Back in the spring of 2020, the politicians — it goes without saying — did not think in terms of culture or Longhouse or simulacrum, but picked up stray signs of a change in the wind, to which their trade, by nature and necessity, has always been alert. They did not waste time pondering upon the old — who could be relied upon to remain tribal or so marooned in their out-of-touchness as not to notice or react to a shift in the direction of party or policy. It was with the young — the future — that the urgency lay. What emerged was not a shift rooted in any deep understanding — by virtually anybody — of what was occurring. The politicians followed the young, who followed the propaganda; the technologically-illiterate old, having lost all sense of authority over the nature of reality, followed the young and the politicians. Again, what began to unfold can be crudely described in these mechanistic terms, at least sufficiently to indicate that it had some form of rational basis — but in reality it manifested as a form of alchemy, some strange unprecedented shifting of the Earth on its axis, some magical transformation born of chronological time, some melting and regrouping of the quantum structure of reality, which, I would say, is how, even now, it best yields itself to apprehension.

We take it for granted that politicians want power, but nowadays, with power belonging mainly to the extra-political domain — the multinational corpo-colonisers, the acronymed supra-nationals, the motherWEFfers, the bureaucrats who slide invisibly on the greased rails of totalitarian ambition — a new kind of politician has emerged who fits this new era precisely: one who wants position rather than power, prestige rather than influence, a State car rather than a licence to change reality, a career rather than a legacy, but who, nonetheless, ‘gets off’ on the idea of power, even though he has none. Power has slipped through political fingers, not just to the multinationals, stock-jobbers and bureaucrats, but into a process little short of miraculous in its stochastic, algorithmic nature, and this too dovetails beautifully with the mentality of the unrepresentable as described by Baudrillard. The minds of the young have been hollowed out and are primed with various forms of distraction as fits the need of the moment when they may be filled with details of the latest psyop or mass formation.

Politics, as a result of these trends, has arrived at an unscheduled midlife crisis. Sheathed in skintight jeans and driving a red hairdresser’s Ferrari, the politician has turned his back on his natural constituency: those who know about the past and its meanings and the role of proclamations and constitutions, and how these phenomena matter in the present. Their heads turned by the scorn of the young, our alleged leaders play the part of medallion-chested lounge lizards who court the mini-shirted, stilettoed bimbos who huddle in groups at the disco giggling into their cocktails at the ludicrousness of their suitors, the pursuit of the unrepresentable by the reprehensible. This mode of operations is perfect for the mission of those behind the New World Disorder.

The onetime Mayor of New York, Mario Cuomo, in an interview with The New Republic, in April 1985, said: ‘Parties campaign in poetry, but they govern in prose.’ He meant that electioneering politicians need to leave the greatest possible room for different interpretations of what they are promising, whereas in the cabinet room there is a need for specificity and restraint. It is a neat and smile-inducing reduction, though probably superfluous nowadays in the context to which Cuomo was referring, a time when politicians are so unprecedentedly despised and yet depended upon and looked to as never before. Their efforts to campaign in poetry provoke nothing but derision, and yet their prosaic efforts at dominion are remarkably effective. Nowadays, they campaign in promises and govern — nay, rule — in psychopathy. Conversely, the public have become incapable of understanding reality when described prosaically; it requires a hyper-imaginative, esoteric explanation to capture their attention and animate them and if it feels like a movie, no matter how nightmarish, so much the better. The tendency of modern electorates to accept almost anything at face value provided it is not prosaic, so long as it may be couched in elaborate explanations with their toes in elaborate poststructural theory and their fingers, ears, nose and tongue in the postmodern.

The issues no longer have to do with electioneering and governing, but with the means by which an electorate may be subdued to the extent of being ruled over. For this, Cuomo’s haikuesque formulation must be reversed: Now it is better to act prosaically and explain poetically. By this method, a modern ‘ruler’ may attain a postmodern level of Machiavellian sophistry, adequate to ruling over his people in a manner that pleases them without any element of affection.

The ‘real life’ simulacrum, then, is a pathocracy. We are, all of us, now the put-upon spouses of shiny-suited creeps with the aura of having dark secrets who threaten and menace us at every turn, as though suddenly rendered volatile and unstable, striking out at us without warning, uttering profane epithets which imply that all the fault for whatever it is that has suddenly gone awry lies with us, the battered ones. It is clear that they are answerable not to the logic of this own ‘households’, but to outsiders, in some remote location — or multiple locations — who issue instructions and protocols of action and behaviour that result in a ubiquity of virtually indistinguishable conditions in multiple countries all at once. These functionaries and their behaviours are not simply eruptions of authoritarianism, nor even expressions of a novel totalitarianism, but simply actors, who believe in nothing and can be filled out with any beliefs those who control them (through money or fear or blackmail) wish to impose. But it is worse than that: They are imbeciles whose stupidity looks like naïveté, who evince a bland innocence in the face of the pleas and protestations of their own people: It’s not us, it’s the virus! It’s not us, its, the climate! It’s not us, it’s Putler!’

Our political establishments have become emotionally unstable, pathological, twisted, biased, desperate and reckless with, for example, their labelling of persons and groups who question them as extremists, which is both a received protocol and an act of desperate flailing at an imagined threat, with a view to subduing their subjects with the notion of an internal enemy. They are captured, seemingly compromised, and far more obviously beholden to external forces than to indigenous pleading. They are not simply authoritarian; but approach in their demeanours, statements and actions a murderous, witch-hunting pitch of vitriol for anyone they perceive as threatening their dogmatic utopian vision for the world. But it is worse than that: They have accepted at face value the indifference to human life evinced by their genocidal puppet masters. They preach the virtue of preserving life, but their every action indicates that they cross their fingers while uttering such platitudes. They no longer care. Their moral calculus, such as it is, has no place for consideration or caring as to whether people die early, soon or now.

Right now, no sane person could decide anything that did not somewhat incorporate the idea that life would be much better for virtually everyone if the political class in its totality resigned and went away, leaving the nations of the world ungoverned and unruled. The trouble, as we have seen, is that words like ‘sane’ and ‘insane’ have drifted away from meaning like carnival balloons slipping from the grip of excited children and floating up, up, up above the wires, and off into the ether.

Baudrillard anticipated not merely the abolition of the real, but also that of political power, which ineluctably followed, and, after that, the loss of the social, which, he said, would give rise to socialism.

In The Procession of Simulacra in his 1981 book, Simulacra and Simulation, he wrote:

Through an unforeseen turn of events and via an irony that is no longer that of history, it is from the death of the social that socialism will emerge, as it is from the death of God that religions emerge. A twisted advent, a perverse event, an unintelligible reversion to the logic of reason. As is the fact that power is in essence no longer present except to conceal that there is no more power. A simulation that can last indefinitely, because, as distinct from ‘true’ power — which is, or was, a structure, a strategy, a relation of force, a stake — it is nothing but the object of a social demand, and thus as the object of the law of supply and demand, it is no longer subject to violence and death. Completely purged of a political dimension, it, like any other commodity, is dependent on mass production and consumption. Its spark has disappeared, only the fiction of a political universe remains.

All this is enabled and concealed by media, whose purpose he foresaw would change from dispensing information and meaning to destroying both. Because we had moved into a world of more and more information, there would be less and less meaning, for the reason that a constant spew of information negates the possibility of any finality of understanding. ‘[I]nformation is directly destructive of meaning and signification,’ he wrote in Simulacra and Simulation. ‘The loss of meaning is directly linked to the dissolving, dissuasive action of information, the media, and the mass media.’

It is the media and the promulgation of information, he writes, that causes the ‘destructuration of the social’, dissolving both meaning and the social, ‘in a sort of nebulous state dedicated not to a surplus of innovation, but, on the contrary, to total entropy.’ Beyond this, there are only ‘the masses’, which result from the neutralisation and implosion of the social. Hence, predicted this former Marxist, on to socialism.

The media, as we have been experiencing acutely in the past 40 months, carries out the functions of destroying meaning and social reality in multiple ways, including:

— telling lies;

— telling the truth on the following day and, on the third day, reverting to the lie;

— telling the truth in the bottom left-hand corner of Page 34, so that, when a protest is raised, it can indignantly be pointed to;

— simultaneously, in the same report, conveying that a story is both true and false.

— attacking those who tell the truth that contradicts all this.

A factor in the growing chaos of the world, indubitably, is the fracturing of reality by virtue of the ready availability of instant accounts of events from elsewhere, something that attacks our sense of the significance of the hereness and nowness of our own moment-to-moment experience of ‘reality’. In the past, news of events in the distant world was conveyed after the fact, at 6 o’clock or 9 o’clock, or in the next morning’s newspaper. When something shocking occurred that somehow broke into our personal realm, we would respond to it afterwards by trying to calculate ‘where we were’ at the moment the event in question occurred. What was I doing at the instant John Lennon was shot? Perhaps I caught a glimpse of Lennon’s face on a bank of TV screens in an electrical shop as I passed on a bus, and was left wondering, as the bus proceeded to the next stop: Has he released another album? The effect of this was not to split reality but to suggest a vast multitudinous world in which events happened randomly and were conveyed to me, because they had happened and by virtue of my interest as a citizen in knowing what was happening. This exalted not merely the individual citizen as someone who required to be informed of events, but also the reality which he inhabited. It was sense-making, and also participatory.

What happens now is different. The news comes instantly, and in doing so suggests itself as more urgent and important than anything I might be doing. It arrives in a manner that suggests my very purpose in being here, existing now, is to await the arrival of this news, to receive it and react. We are all simply audience members of a News-day. The bulkiness of the smartphone in my pocket is a constant reminder that I am in this mode of waiting. Life is elsewhere, and I merely sit in suspended animation, anticipating or awaiting some new calamity or sensation to have occurred in some distant place. I live, therefore, not in the place I happen to be, but in all the other places in the world that might potentially be the occasions or locations of reports pinging through on my smartphone, which is to say virtually everywhere, with emphasis on the virtual. I am everywhere; where I am is nowhere, the hole in the doughnut. At the same time, there is a suppression of any sense that the events being relayed to me are even occurring at whatever distance is implied. They are the only ‘here’, and the only ‘now’. We are cast into them, and therefore removed from the actual world. We experience momentary faux emotions as each event — each air raid, each tornado, each celebrity death — comes and passes. In the future, our ‘memories’ will reflect only these ‘stories’, and all vestiges of our actual experiences will have evaporated. I live in the entire world, except the part of it where I sit or stand or lie, which means that I too am abolished, disappeared, unless I can make myself visible by becoming the subject of a news report, a remote possibility. Reality is fractured, but not cleaved in two; for actually existing reality is no longer capable of competing with the virtual kind, which is always there, always brimming with happenings, which fill the emptiness of my presence in the ‘here’ and the ‘now’ in a manner that destroys both the hereness and nowness of things. Not only is there no reality, but humanity itself begins to doubt its own existence.

In this new model, news programmes on television, for example, are no longer, actually, news programmes, but performances of prepared scripts that are written to create crafted impressions of what is ‘happening’. Since I do not watch television, I have only recently begun to understand this syndrome — mainly as a result of occasionally finding myself in a room with a switched-on TV set, which I am not in a position to turn off. The change from even when I stopped watching television, just short of a decade ago, is instantly palpable. Some items, relating to inconsequential stories, are more or less unchanged, but anything in which the manufacture of the simulacrum is at issue, such as (of late times) Covid, Ukraine, climate, transgenderism, homosexuals, coercive mass migration, and suchlike topics, is packaged more of less as a short piece of theatre, in which all but literal ‘actors’ (and sometimes those too), who have been vetted as to what they might say, and most likely coached to refine their contributions so they function adequately to convey the pseudo-reality, are used to fill in various parts of the script. People who watch television a lot may be unable to perceive the falsity of this, whereas those who abstain from watching assume that what is happening on television is merely the promulgation of directed, controlling, always slightly twisted information so as to ‘influence’ their thinking. In fact, what is happening is beyond mere lies: It is constructed falsity. It is the material of an alternative reality reproduced to replace the actual real, and to conceal the ‘genuine’ reality’s prior abolition.

This ‘scripted journalism’ has many other manifestations, which artfully mimic the patterns of what we once may have trusted as ‘true’ reporting, but are actually designed to confuse, confound, to spark false hopes, to have people doubt their own eyes, ears and memories, to provoke people to secrete hostility towards certain others, and ultimately to instil submissiveness and despair. Among the many important aspects of this kind of ‘news’ management and presentation are the techniques of compartmentalisation, coordination and constant repetition. The repetitiveness bears resemblance to the manner of the play-listing of pop music on radio, which enables the hooks of favoured songs to be hammered into the heads of the audience.

Among the many techniques used in this kind of programming are devices that enable occasional minor — but more often major — untruths to be inserted in the programming, controlled explosions of truth which, not being reiterated multiple times, may as well not be mentioned at all. An example might be the way that, in late March of 2022, Boris Johnson flew from London to Kiev with the purpose of scuppering the peace talks then taking place between Russia and Ukraine. This was reported at the time, but soon ‘forgotten’ by virtue of not being constantly reiterated. This provides deniability in the event that someone subsequently accuses the broadcaster or newspaper of failing to report something, and yet the absence of emphasis ensures that it never reaches the point of arousing the curiosity or doubts of the audience, which never gets to actually ‘know’ the information in its true context and meaning.

The ‘far right’ narrative, much in favour among journaliars in the Time of Covid, is another salutary example of scripted journalism. It is actually a device to galvanise the ‘in group’ of the groupthink, by constantly referencing the (largely fictional) ‘out group’ — this sinister and blurry manufactured spectre on the outside, that somehow — it’s unclear how — threatens to invade the group and subject it to Hitlerian methods of manipulation and Maoist techniques of terror. That the 'far right’ does not exist does nothing to deter those engaged in spreading the lie. On the contrary, the lack of evidence for the existence of the ‘far right’ tends, in the climate being created, to heighten the public sense of the danger. The ‘far right’, like Covid, can be asymptomatic. The evidence for its existence is its absence. That it is nowhere to be found 'proves’ that it is everywhere; that it says and does nothing implies a menacing, brooding presence that might strike at any moment.

The reason such abuses of truth are possible is because of an unannounced contract of omertà that pertains between the media and political and official entities and bodies, in which the business model of media is flipped from truth to lies — all this being made possible and permissible by the conditions of the simulacrum. The deal is that the media will do or say nothing to draw attention to the perpetration of fraud, or the institutionalisation of mendacity, but will report deadpan whatever is issued by way of a formal script, no matter how ludicrous, spurious or contradictory, by the Regime. This means that the Regime is at all times guaranteed that none of its nefarious acts or statements will be highlighted sufficiently for the ‘coverage’ to have any meaningful impact. This means that there is never, as in the past, a ‘Gotcha!’ moment, a calling to account, a delivery of judgment on political stewardship or behaviour, which in effect means the abolition of the Law of Consequences in the execution of the media’s traditional role of calling power to account. Since there is no longer any real power (none accruing to the politicians as such, having all been devolved upwards out of visibility and accountability), the exercise of covering political life has become a kind of game, in which, even as the stakes grow higher and higher, the conscience of journalism has been set so low as to render these behaviours as though victimless and harmless.

Real journalism used to enforce real consequences — it was the cultural equivalent of policing. This used to mean that a ‘story’ was not simply a space-filler or a piece of entertainment — it had meaning in the real world. Just as, watching a movie, a play or a TV crime series, you could expect events within the story to result in consequences towards the end, so it was in real life, largely thanks to honest journalism. This is partly why journalists came to refer to their material as ‘stories’. As the story unfolded, it would become the subject of public discussion: ‘Heads will roll!’ ’Is so ’n’ so toast?’ ‘Will she have to go?’ ‘She’s a goner!” Will the government fall?’ Et cetera.

Tony Blair’s spin maestro, Alastair Campbell, used to say that if a politician who becomes the subject of a negative media story cannot get that story off the front pages within a week, he or she is ipso facto toast. This observation bespeaks a naturalistic process within the operation of news that ensures a real-time dynamic of consequences arising from the public ventilation of a particular issue.

All this was abolished in the Covid episode. The ‘purchased’ nature of media ensured that ‘stories’ would no longer have consequences — or would have consequences only for those who sought to question the ‘authorities’. In this model of ‘media’, the management of every ‘story’ ensures that meanings are all the time within the control of the ‘authorities’. All news content is released or eked out in a process of constant collaboration between governments and ‘health authorities’ on the one hand, and media managers on the other, to ensure that it achieves its intended purpose, which no longer has anything to do with informing the public as to what is happening in the world. The purpose is to manage public perceptions to the extent of imposing a false version of reality on the public imagination. This model has now endured with barely a stumble for the past three years, a period in which the Covid fiction, and related inventions, would continue to be believed, and anything with the potential to damage that objective disposed of or minimised. In this netherworld of pseudo-reality, the authorities are never ‘guilty’ of anything — blame is a condition accruing solely to those who criticise the authorities. Because what is on the news today appears to contradict what was on the news yesterday — without any accompanying corrective or clarifying narrative — does not mean that either or both versions are wrong, or that there is any necessary contradiction between them. The authorities will explain all this in due course, and meanwhile we should continue to believe in their good intentions.

This is an entirely new phenomenon in the public and political life of our nations. All our lives, we have lived with an approximately reliable expectation that when things of significance happen they will be reported in the media, and that when the story changes it will be subject to updating or correction. Furthermore, if the authorities err or do wrong, it is the journalist’s job to expose this. These became almost reflex assumption of viewers, listeners and readers, implicit promises that were accompanied by the constant tacit assurance that, if something was reported, that report was the most accurate and truthful account of events that journalists could assemble at a particular deadline moment or hour, and would be followed through in all its implications until the public interest was entirely discharged.

The problem is not just that this is now changed utterly. The even more radical effect is that most people, being unaware of any change having occurred, continue to trust the media as though it were some kind of 3D photocopier of total reality. The citizens, fearful or merely watchful, look to the sentry posts and see that they are manned, and breathe sighs of relief. But the figures at the posts are men of straw.

Most people have no idea that the information they are being fed, on a number of key topics, is constantly subject to manipulation and spin. This has the effect not so much of splitting reality as obliterating it and replacing it with a remote, virtualised simulacrum in which, though the environment appears to remain unaltered, the ‘content’ of the culture is utterly different. There is, at the same time, this ghostly impression of actual journalism. The nature and presentation of the article or report seem to suggest something like the same context as would once have resulted in a dramatic playing out of consequences, but here there is simply this faint jaded sense of another stroke being pulled. It is like trying to light a fire with wet sticks: The ingredients all look more or less the same, the match lights, the firelighter takes, the rolled-up newspaper ignites and burns energetically; but a few minutes later there is nothing but a smoking mess of blackness.

This, I find, is an aspect of what has been happening that almost no one has noticed or understood to its depths. Even when people perceive the wrongdoing of the ‘authorities’ and the venality of the journaliars, they seem to regard these behaviours as though aberrational malfunctions within a normative system of naturalistic call-and-response. In fact, what is happening is a complete travesty not merely of the news but of the process by which news has long been apprehended. As a result of absorbing such ‘stories’ over three-and-a-half years, the public has become ‘trained’ to suspend its sense of expectation concerning any particular story, unless a process of repetition and coordination conveys that it is 'reasonable’ to do so.

What this means, in sum, is that the authorities, through their corruption of the media, have built a glass, bulletproof cage for themselves to operate in, where they are in effect impervious to criticism and consequence. This process has not even begun to be understood, and has no discernible prospect of termination. Each new development, no matter how potentially harmful to the perpetrators of the Most Heinous Crime in History, can be ‘explained’ away, in what appear to be logical and reasonable terms, always presenting the motives and intentions of the authorities in the most auspicious light possible. The outright compromising of journalism in this period ensures also that journaliars have no motivation to expose this process, or own up to their own part in it. This wicked symbiosis, therefore, persists at the centres of our public squares, pumping out a pseudo-reality that is impenetrable even by those who are able to perceive something unusual, because the vast majority, even when something rings strangely, assume the discordant note to be simply a necessary and logical side-effect of the process of emergency truth-telling. But it is important to stress that the appearance of this pseudo-reality is such as to be quite the antithesis of mendacious. Its veracity is beyond question because it is not simply a version of reality — it is, or appears unquestionably to be, a description of reality such that any attempt to tell the truth will itself seem to be mendacious and/or paranoid. It does not conceal the truth to conceal reality — it supplants both.

Spending a few hours, days or weeks immersed in Jean Baudrillard’s challenging but vital description of the undertows of our culture in time, it is impossible to shake off the thought that his analysis, though complex, sometimes improbable and sometimes seeming to be no more than ironic wordplay, contains more than a sense of providing some kind of sketch, at least, for what has been happening to us in the ‘real’ world more than a decade after his death.

In late spring this year, I emerged from such a period of immersion in his works, to be confronted by two potted rhubarb crowns gone to seed in my greenhouse after I placed them there to protect them against a promised late frost, and went away for a few days. They had, in the exquisite horticultural term, ‘bolted’ — both crowns having sent up tall shoots — more than six foot high — with pods of seeds at the business ends. Such an event can amount to a quite radical setback: the seeds are rarely very useful and the plant has expended all its energy in this vain gesture — all arising from the sudden change in conditions, which confuse the plant’s ‘hormones’ as to the actual time of year. The only remedy is to cut the errant shoots back and, in the case of rhubarb, plant the crowns outdoors and hope that they will settle down to a normal existence.

It dawned on me that this might be a close to perfect metaphor for what we are undergoing in the socio-political realm. Western civilisation is in the throes of a process not dissimilar to ‘bolting’. Having ‘evolved’ beyond the subsistence and prosperity stages, we have entered a phase in which — to borrow my mother’s persistent admonition to us as children: We don’t know what to do with ourselves.

As a result, under a process of malevolent manipulation by nefarious forces, we have succumbed to a condition that civilisation had hitherto strived to sublimate, but which is as though baked into our biological structure: the impulse to ignore our limitations in the hope of discovering new vistas and perhaps the beginnings of perfection. Western civilisation, which seems to be in a death spiral of demographic collapse, despair, nihilism and self absorption, is in reality seeking a new way of being, having appeared to exhaust the old one, but really has arrived at a state of unprecedented confusion, having been misled as to the causes of its confusion, and confused all the more by the sly interventions of malevolent actors.

‘Bolting’, also called ‘running to seed’ or ‘going to seed,’ redistributes a plant's energy away from the leaves and roots to instead produce seeds and a flowering stem that wastes the plant’s energy to no good purpose. Bolting usually signals the end of new leaf growth, and indicates that the plant has passed its optimal state. The phrase 'going to seed' means 'to deteriorate'. It is derived from the natural act of annual and bi-annual plants going to seed at the end of their lives, and is provoked by the plant’s intimation that it ought to reproduce itself. When it happens at an earlier stage, it can amount to disaster, even for a perennial plant like a rhubarb crown.

The ‘bolting’ metaphor can be replanted in the technological, the political, and the cultural arenas, in all of which the surge occurs as a process of human alteration, distension, and intensification, as we struggle to achieve continuity in alarming new conditions that we can but remotely and clumsily comprehend. In the human context, the syndrome manifests as various forms of behaviour indistinguishable from madness. Under the attrition of propaganda, we are convinced that what is happening amounts to ‘progress’, when in reality it is a sign that we need to go back to the ABC.

Outside of certain postmodern circles, it is commonplace for public commentary to assume that reality is something fixed in particular foundations, and therefore an objective phenomenon exhibiting a constant shape and character. Baudrillard and others take a different view: that reality, standing there, is as much the creation of the descriptions and representations as it is of any scheduled process of production — a reapplication of the ‘observer effect’ in physics. It would be understandable if we experienced difficulty in accepting such a theory as having any applicability to events in, for example, the geopolitical or social contexts — after all, we have observed such events all our lives and have been able, approximately, to comprehend them; and yet, we cannot dispute that, more and more, only the utterly esoteric seems to gain traction in attempts to explicate or understand where we have fetched up now. We should remember that we have lived through times of exceptional technological and cultural change — at least at the level of consumer devices — and that, in our apprehension of this, we are more than likely working with tools of reasoning that have been developed and utilised in utterly different — more prosaic — conditions. Thus, the difficulty we have in comprehending the leaps that are necessary in order to achieve sense may have to do with the suddenness of the changes, accompanied by — paradoxically — the relative slowness of the evolution from one form of reality to the other. Things are changing — ‘suddenly’, ‘dramatically’, yes — but not so fast as to alert us to the necessity to change our viewfinders. Despite the turmoil, we are still reading the transformation as an organic shifting, and are relaxing into a kind of complacency when really we ought to be on red alert.

The problem may be that what we are looking at may be a kind of ghostly after-image of an old reality, already supplanted by something that fits the vacated place and bears a passable resemblance, but is (‘in reality’ — hah!) something entirely other. Baudrillard assists us with this in his reflections on the ‘image’. Once, he warned, the object was indeed all there was; now, the object is merely a starting point, a fleeting entity that immediately becomes an image, and may no longer be there, or may have been, in the first place, an instrument of misdirection or a figment born of and reproduced by propaganda.

For him, the catastrophe had already happened. We had entered a kind of paradise, or at least crossed the line into the future, in which the past — history — no longer had the meanings it had before. Man’s construction of history, he argued, had long been a form of simulation, since it ordered events in such a manner as to destroy their randomness and imbue them with meaning. For this and other reasons (victory bias, for example) history was neither credible nor convincing. Only by creating a simulation of reality could history be managed as a kind of backstory of humanity, trundling forward towards some kind of culmination, a necessary backdrop for ideological salesmanship. This meant, in effect, that the ideology of progress always demanded the falsification of history, and therefore also of the present, an interference that occurs even while the event under consideration is happening. Contrary to our assumption of naturalism, this tendency to deliver meaningful stories by way of history and current affairs is a quirk of our culture in which randomness and unpredictability have been ‘managed’ before they arise. The obituary of public figures are written long before they die, and pandemics and other ‘acts of God’ may be subject to rehearsals just months before they occur.

We have crossed the road to move into the simulacrum, carrying all our clutter and kit, sleepwalking through the night to find our new homes in the virtual and waking up in the morning with just the vaguest sense of having moved from someplace else. We enter the simulacrum and becomes its citizens, taking it for the real. We are as avatars, facsimiles of ourselves, standing outside our selves and moving our beings about as though pieces on an electronic chessboard, or symbols on a handheld video game.

Technology, of the sort we are speaking of here, collapses time, eliminates the process of maturation, and delivers a passable imitation of maturity which is really just a shell, inside of which is emptiness. This is especially visible in young males, who have always been the ones who must come to grips with the external world at a moment when they remain inexperienced, unrefined, immature, naive, but nevertheless required to shoulder the physical cost of ‘progress’, sometimes by offering up their lives.

As we have observed again recently in the proxy war in Ukraine, it is young men who must pay the ultimate cost of the follies and conceits of politicians and ideologies. Here we go back to The Longhouse, and L0m3z’s description of its contemporary state as, I would say, a matriarchy disguised as a patriarchy, ruled over by the Den Mother. In this sense of its camouflaged reality, it provides a metaphor also for the simulacrum.

Robert Bly warned in Iron John that the elimination from our culture of the teaching, benign-authoritarian father had left us with generations of young men who were ‘numb in the region of the heart’. Because young men are never allowed to come away from their mothers, they stand on the threshold of manhood but cannot enter. The umbilical cord had been severed, but little more. Still tied to their mothers’ apron strings, young men struggle to find ways to announce their manhood. With their fathers cast into silence, they are starved of the wisdoms and mythologies that might sustain a healthy male existence. They have no experience or sense of what male emotions might be like, and are therefore presented with a choice between having female emotions or no emotions. Often, they choose to have no emotions, in which case their options are reduced to nihilism or self-destruction. Today, as L0m3z reminds us, we have elevated this condition to that of, yes, pandemic. Adrift in the numbness that engulfs them, many of our young men now walk with an outward appearance of normalcy but inwardly lurching uncontrollably — lurching from, for example, a learned piety to intense rage — all the time seeking something to provide some illusion of feeling while simultaneously keeping the numbness at bay.

We need to get our Longhouse in order. But this needs to be preceded by a conversation in which the truth is permitted to be heard.

The ‘liberation of the networks’ has caused the truth to be buried deeper than even before. The technology delivers articulateness, cleverness, sophistication, knowingness, jadedness, wryness, exhaustion. It delivers these even to a terrified 12 year-old boy who has seen nothing, known nothing, experienced nothing, felt very little but fear and anxiety and, when he is lucky, a little hope that all the troubling, confusing things that seem to be true will one day dissolve and be replaced by order and guidance and — whisper it — values. He has searched in himself and in the world for the ideals that he intuited from the stories his mother or older sister read to him as a boy, but cannot find anything to begin from. Reality is disappointing — slow and unresponsive, incapable of delivering anything like the feelings he has intuited from screens since before he could read. He has delved into the depths of his fantasies and known everything that human sexuality is capable of delivering, but without the human element. He wants to feel something but experiences only victimhood and loathing and a flimsy kind of hoping that seems to have no evidential basis in anything he encounters. He subsists in something akin to the ghost of a chemical addiction, which has frozen his heart in terror and chilled his soul into hiding. He has sequestered himself away in his room with his Gameboy and taken this for life. He has discovered the World Wide Web, which seems to be a place where you can live without being alive, a place where you can send messages to people you don’t know, and keep things like that. His body has grown, his vocabulary too, his penis is hungry and prone to an iron hardness, but his heart has shrivelled for want of sustenance and his emotional life exists purely as virtual reality. Because the world is something that comes to him through the thing in his hand, he has no reference points besides. He cannot touch or hold or seize or dismantle something in an attempt to understand how things work, what things mean. This, tentatively, is the beginning of what we are talking about, for without knowledge of the true nature of manhood, the boy is doomed to self-detruction or worse, and by virtue of this our societies are doomed to the haemorrhaging of spirit and fight that might, in other circumstances, have served to defeat the forces that now threaten us all. This was the first and most fundamental of the attacks mounted by the arch-manipulators, intensified now by the flooding of our societies with military-aged men from cultures unaffected by the emasculation process. We are on a hiding to nothing.

To establish the roots of this catastrophe in what remains of the ‘real’ world, we need to look to any technological development as such, but to the condition of The Longhouse, not just the symptoms described above, but in particular the corruption of education, its replacement by what I call ‘seducation’ — a deliberate process of instilling the anti-values of noncery in the heads of children who, having made their approach through the already twisted culture, rarely have the wherewithal to question it, and — looking up to see if their elders are as agitated as they — note the lack of perturbation all around.

Preceding or coterminous with all this was the destruction of Christianity, which removed from the culture not merely morality and empathy and hope, but also the capacity to walk upright through reality towards some indefinite but constant point, and the sense of why this was essential. More or less simultaneously, science was replaced by scientism, an ideology of certainty that dismisses and destroys democratic opinion (and ultimately democracy), as well as all lived human experience. This was accompanied by a pseudo-democratising of communications, whereby the most idiotic voices took over the square of public conversation —or, the ‘town hall’ — replacing wisdom and actual experience with vitriolic opinion based on nothing but repetition of what was already overstated.

The nature of the way we apprehend knowledge paints us into the totalitarian corner. Once, regular people knew a little about a broad range of matters, from politics to fashion, and intelligence resided in reconciling these various elements and comprehending their connections. But today we live in an era of compartmentalisation, whereby each person is ‘educated’ to know more and more about less and less: each discipline is fragmenting into ever more numerous sub-categories, and each individual is more and more driven into some particularised zone of ‘expertise’, in which proficiency offers the path to income and respect, which is to say dignity, but not to wisdom or reason or common sense. Thus, unless one is disposed to become a politician — which almost nobody is — becoming interested in the minutiae of politics is not merely boring, but also potentially impoverishing. Politics and politicians are permitted to crack their whips so long as they agree to remain at a personal distance and speak in the strangled languages of pop culture. But they are not respected, and no longer even liked.

In much the way that he describes the world as having passed a point of rupture, Baudrillard himself in his work crosses an invisible line between sociology and philosophy into art and metaphysics. His insights can sometimes seem close to impenetrable, but they are worth pursuing, if only because they sketch out the territory in which we must all henceforth consider ourselves. He takes a perverse view of human nature, deciding on something close to masochism as a remedy for man’s postmodern condition. Where I part absolutely with him is when he insists that reality can have no meaning and that this is something we ought to embrace, that affirming meaninglessness is actually liberating: ‘If we could accept this meaninglessness of the world,’ he wrote in Impossible Exchange (2001) ‘then we could play with forms, appearances and our impulses, without worrying about their ultimate destination . . . ’ Citing the Romanian philosopher Emil Cioran, he declared: ‘[w]e are not failures until we believe life has a meaning — and from that point on we are failures, because it hasn’t.’ Instead of fighting the world of images and objects, he insisted, we should simply embrace its rule as a quasi-metaphysical absolutism, seek out its essences and mysteries and become conversant with it. We should surrender to the object and the screen because we have no future independently of them.

This, in turn, means acceptance of the default sadomosochistic dominion of the New World Disorder — the hidden puppet-masters and their localised proxies who crack the whip and call the shots. But this would be to kick the ladder from under ourselves, leaving no way back to ‘reality’, on the presumed basis that humanity itself is unwilling to go there. By taking this avenue, man would be turning his back on the option of imagining a divine master, or fearing His wrath or punishment. In these circumstances, humanity would become its own gaoler, and only those with long memories remain sentient enough to resist this. The eradication of the transcendent would be a ‘perfect crime’, imprisoning us in a manufactured ‘metaphysics.’ This, above all, is wrong, not merely because it is false, but because, even if it were true, its logic would destroy the sole surface upon which experience tells us man is capable of achieving traction in reality, which is the only locus of his hopes of a meaningful existence.

Right now, we need belatedly to bring our young men together and gather them around the campfire at the edge of the forest, to talk to them about manhood and pain and wounds and history and story and love and death, and explain to them why they were allowed to grow without faith or hope, as though they wee unworthy on account of having committed some unnamed crime, and how all of the things they have come to fret about and fear were not their doing but the sins of our culture gone to seed.

And then we shall have ask them to forgive the wrongs that were done to them.

And then we must ask them to stand in the breach for the battle that is coming.

Have we the right to ask this of them? I do not know. But neither do I know of any other option for saving Western civilisation.