Nell: Slouching towards Bethlehem

'And watch two men washing clothes. One makes dry clothes wet, the other makes wet clothes dry. They seem to be thwarting each other, but their work is a perfect harmony’. — Rumi

Goodbye, ‘God Nell’

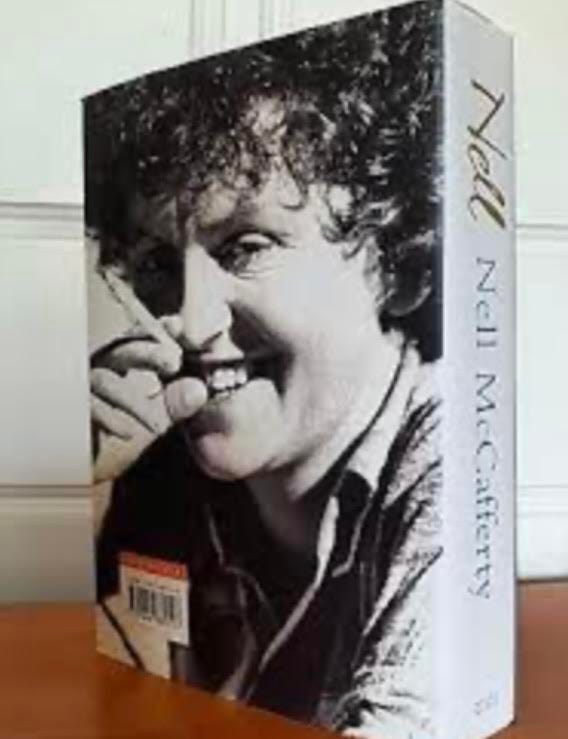

I do not have many feminist friends, but there was one feminist icon with whom I was on exceedingly good terms for many years — remotely, most of the time — the (Irish) Mammy of them all. Her name was Nell, and she died during the week. For the benefit of foreign readers, I will add that her surname was McCafferty, but for Irish people this is superfluous, the most redundant surname since Presley.

Because she was the best known and longest serving and most ferocious of Irish feminists, she and I might have been expected to be enemies, as anyone who read my article of a week ago might immediately intuit. Actually, we were good pals going back to the mid-1980s, when I was Editor of In Dublin magazine and she was one of my columnists — the best of them, as it happens. I would not call us friends, but nor would I say that we were mere acquaintances or ‘colleagues’ — we got on much better than we should have. The first time we met was in the tiny midlands village of Granard after the Ann Lovett horror, which transfixed the nation in February 1984, and Nell wrote an electrifying article for In Dublin (before my time — I was then with Hot Press). I met her in a pub in the village, and we started talking because, I reckon, she fancied my girlfriend, but the upshot was that I blew my cover and was shortly thereafter invited to leave town. The locals, understandably, were not overly keen on reporters. Nell, for whatever reasons (iconic?), was permitted to stay, casting another doubt on the Feminist Manifesto.

At that time, I was a wishy-washy leftie-liberal. By the mid-1990s, I had started to write differently about the world on the basis of three experiences: going to Prague in 1990 for the first free elections after 40 years of communism; giving up alcohol; and having a daughter in circumstances whereby I found myself amenable to the State’s unlimited tyranny on the simple basis of being a father rather than a mother, and finding that my leftie-liberal compadres were keen to shut my mouth about this. As a result of these Damascene moments, I abandoned my wishy-washy liberalism and started to write truthfully about what I encountered and observed, becoming a pariah among my former allies. I expected that Nell would be among them, and indeed did not meet nor hear from her for a few years. Then, one morning, we found ourselves sitting in the same green room in the ‘national’ broadcasting station. She was the same old Nell. I had recently published a collection of writings about men, manhood, feminism, family law and related matters, in the Introduction to which I had outlined the three aforementioned reasons underlying my change of direction. In a pause in our conversation, she said, ‘I read your book. I found the Introduction really moving.’ For someone who had for a decade been ‘Ireland’s leading misogynist’, this was one powerful compliment to receive from the doyenne of Irish feminism.

She recognised me for who and what I was. She called me ‘Young John’, stripped of condescension and with just a soupçon of irony. She did not adopt slogans or pejorative labels and apply them to individuals on the basis of their views, regardless of her own position on anything. She understood that life was complex and contradictory, and no one had a monopoly on the definition of reality. She and I both emerged from a time when journalism was passionately subjective, but not personal, a time before all the pundits became puppets. She was a world-class writer, who — as I told her repeatedly — never wrote half as much as she should have.

There was an episode a few years ago — in the spring of 2018, actually, shortly before the referendum on the Eighth Amendment — in which Nell made a number of what were, even for her, quite explosive statements on the topic of abortion. I did not have a platform at the time, but wrote an essay about the incident, in which I reflected on the Nell I knew and on the likely meanings of what she had been reported as saying.

Here are some extracts from that article — unpublished until now — which was to be titled ‘Slouching towards Bethlehem’:

Nell. That was all we needed to call her. The name McCafferty invariably appeared on top of her articles also, but it was superfluous. She was ‘Nell’. Few scribes in this ‘modern’ Ireland of ours have attained such a status of iconography. She stands alongside Gaybo, Charlie, and a handful of other public figures, for whom one name suffices for instant recognition.

And the very utterance of that name, on the streets and roadways of Ireland, was swaddled soon in smiles of fondness. Nell was deeply loved — adored by the women whose case she made better than anyone had ever made it, admired even by the men she sometimes upbraided, often excoriated, always drove crazy, but very often forced to laugh out loud at her humour and chutzpah, or at the absurdities she had pointed out in themselves.

Nell. On the Late Late Show, in the pages of The Irish Press and In Dublin magazine, she was the gruff truth-teller with the twinkle in her eye. In her pronouncements, judgments and demands, there was passion but no visible animus — unlike the dramatis personae of the present time, when those who command the public square to demand no less than that Ireland turn itself inside out to please them seem to exhibit little other than pure hatred. She gave the impression of bravery, though one always suspected that, as with all those who exhibit great courage, Nell was not devoid of fears, but simply had acquired the capacity to rise above them.

When I was her Editor for a couple of years, in the In Dublin of the mid-1980s, I had the great privilege that came with the certainty that every column she delivered would be clear and gripping of word, taut with equal measures of insight and irony, and delivered like a song fit to be sung by Beniamino Gigli. I was also, from time to time, her hapless adversary, the one opposite her on some radio or TV panel. And then I was the one needing to dig deep in search of courage, for she was formidable and merciless and, above all, head-wreckingly funny. Once, on a TV panel, I sat beside her and ‘enjoyed’ an opportunity to observe her modus operandi. I had a maroon manila folder in front of me, with notes relating to one of the issues we were to discuss (the career of the other feminist icon, the decidedly more prosaic Mary Robinson). ‘What’s in your folder, young John?’ she whispered to me as the red light came on. I blushed the colour of my folder and mumbled something about statistics. Shortly afterwards, she went public with the folder issue. The moderator, John Bowman, asked her something and, instead of addressing the question, she replied: ‘I wonder what’s in Young John’s folder?’ She never got to answer the question.

But then, no matter how hard or heavy it got, I could be certain that, as I walked out the studio door, Nell would catch up with me and ask after my daughter Róisín, or say something gratuitously generous about something I had written. And that was praise indeed. Few people would anticipate that Nell and I might be on friendly terms, but we have been for years — not close, by any means, but able to trust one another with pretty big stuff. In my times of travail, it was Nell who wrote me the sweetest, kindest notes, with a little truth-telling in there too.

Nell loved Ireland, with a palpable passion. She also understood Ireland, at a level that few others did or do. From Lough Foyle to Ballydehob, from Ringsend to Belmullet, in the highways and byways, perfect strangers walk up to her — I’ve seen it many times — say ‘Howiya Nell’ and begin to talk as though to sister or mother. As part of the Irish counterculture of the 1970s and beyond, she was unparalleled in her capacity to summon up the spirit of the Irish nation and its people. To be honest, most of the time, she was the Irish counterculture.

To the best of my knowledge, Nell never wrote fiction of any kind, though she may have some gold in her bottom drawer. Her published work took the form of essay, polemic, memoir and profile. She was an editor’s dream: you would lie awake at night thinking about what she might come up with. Her 1960s ‘In the Eyes of the Law’ series for the Irish Times, in which she simply sat in courtrooms and wrote down what came to her as she listened and watched, remains one of the great testaments of its time. Setting aside the outside world’s loss that it never quite got to hear of her, one can incontrovertibly say that Nell belongs in the pantheon of modern literature, an undiscovered Wolfe or a Mailer, comparisons she would appreciate even if stretched to a mention of her feminine machismo.

Nell. It strikes me that we may some time back there have slipped into a tone something like an obituary, but luckily that would be way too premature. For Nell is still with us — very much, as it turns out. [Reminder: this was written in 2018!]

Nell is not writing regularly nowadays, which is our loss at least as much as it is hers. But a week or so ago, she hit the headlines after something of a long silence, speaking at a Women in Media conference in Ballybunion, Co Kerry, and making clear that she had lost none of her capacity for surprise.

She spoke about abortion, of which she said she had been a ‘reluctant’ supporter.

She said: ‘I’ve been trying to make up my mind on abortion. Is it the killing of a human being? Is it the end of potential life?’ Then, being a woman who belongs to a generation that felt entitled to think out loud, she said: ‘But it’s not that I’m unable — I am unwilling to face some of the facts about abortion.’

This, by the way, is a measure of what we have lost with all the gotcha stuff and twitty literalism that places every half-sentence on trial and does not stop until you can hear the vertebrae snap. This was the way public conversations used to happen before: someone would say something they weren’t quite sure of, and someone else would take it further or pull it back, until something of a dry path of common ground was reached.

She went on to say that she had come to believe that pro-life advocates were right when they said that to allow terminations at the 12-weeks stage of pregnancy would mean the dismembering of babies in the womb. Back in 1983 [when the Eighth Amendment was passed], she said, she had called this argument ‘nonsense’ — when pro-amendment advocates showed videos and said exactly that. A month ago, in a powerful article for the Irish Times, the paper she graced as a young woman, she spoke of the impossibility now of having even a constructive discussion about these matters. She recalled a conversation back home in Derry in 1983 with her mother who, opposed to abortion in principle, had become upset on Nell’s account by pro-life propaganda saying that abortion was, without qualification, the killing of an unborn child.

Nell had moved to clear the matter up: ‘“No,” I explained, “in the early stages of pregnancy, what is in the womb is a collection of cells that would not be visible under a microscope. That collection of cells could in no way be described as a baby,” I said confidently, and dismissively. (I was 39 years old.)’

Nell described her mother rising to her and saying, ‘Come you out here to the scullery with me.’ Nell followed her out to the window looking on to the back yard. Her mother pointed to a spot on the floor. ‘Do you see that oilcloth under my feet?’ she asked. ‘Are you telling me that the day I miscarried onto a newspaper on that exact spot, that I miscarried a bunch of cells? That was no bunch of cells, Nell. That was my baby, four months old.’

Nell took up the story in her own words: When the doctor arrived, he told Nell’s mother that it was the most perfect specimen of a miscarried baby that he had ever seen, and asked her permission to send it for preservation to a medical laboratory in Edinburgh.

‘I asked what the specimen looked like and my mother replied, pointing to a framed Lowry picture, that it was like “one of those stick people in that painting up on the wall”.’

Nell wrote in that Irish Times article, and also told her audience in Ballybunion, that she had recently Googled what pregnancy looks like at 12 weeks. The babies, she said, ‘suck their wee thumbs and they have toenails, fingernails and arms and legs.’

She said that in an abortion ‘they scrape the contents of the womb. The pro-lifers are right. Out come the wee arms and legs, and I thought: “Oh God, is this what I am advocating?”’

When she was young, she said, abortion was ‘beyond our consciousness’, but here we were now, ‘100 years after slaughters like the Somme and places like that, offering abortion on request.’

She then changed tack and doubled back to speak about what she called ‘the nightmare of unremitting pregnancy’. Asked a direct question under this heading, she said she would be voting on May 25th [2018] to repeal Article 40.3.3 [the Eighth Amendment], the sole remaining protection in the Constitution of Ireland for the unborn child. The amendment was carried, two to one.

‘I believe that abortion is necessary and to have it as freely, legally and widely as possible,’ Nell told her audience in Ballybunion. ‘Ireland, she said, ‘is a cruel country in which to be pregnant.’

‘I am forced to advocate abortion. Even though I know it’s necessary, it is grim and I am sick of it, 100 years after we ended the mass slaughter of World War.’

What she said was numbingly frank, seemingly devoid of guile or obvious calculation, but also perhaps the expression of a deep confusion within herself. There is no law against confusion, and, even if it were so, then it was the same confusion that evidently right now grips also perhaps half of the country, addled as we are with incessant propaganda and disinformation. That it should haunt the public sentences of the most iconic feminist intellectual Ireland has seen should give pause for thought to lesser thinkers, feelers and articulators.

Be that as it may, it remains a grave confusion. It is not coherent to equate the slaughter of unborn children with the bloodshed of the Somme and then go on to say that this modern bloodshed is ‘necessary’. It is disorienting and bewildering to have someone describe what she clearly accepts is the killing of an innocent human being and then to learn that she has gone on to say that she will vote in a few weeks to ensure that this practice becomes a guaranteed and protected element of Irish law, replacing the fundamental right-to-life with a fundamental right-to-kill. How can homicide be ‘necessary’? How can the slaughter of innocents be unavoidable? Nell says she is ‘sick’ of it — of the killing, yes, but also, one presumes, of the doubletalk and dissembling and equivocation and avoidance. And she’s not alone there. I have never before known Nell to leave an argument or a sentence unfinished, and now is not the time for her to begin.

When I read what Nell said in Ballybunion, I was exhilarated and hopeful, then sorrowful and frustrated. For here was a woman who all her life had striven to be completely truthful in public, still doing it, trying to reconcile the beliefs which had formed her as a young woman and as a feminist activist later on, and what she had come to understand as she walked down the avenue of her autumn years. But what she said, though emotionally decipherable, made no sense at all. It was like the utterance of a person in the very throes of changing her mind, spoken at the precise moment when two mutually irreconcilable views were jockeying for supremacy in the womb of her intellect. What came out, if this is the case, was not one position but two — albeit one fresh and raw and vibrant with a new awareness, the other the reiteration of a series of grievances that are not of the same order or moral weight.

You might say that, once again, Nell McCafferty had spoken as the voice of her country’s zeitgeist. But if she had, it was to say several contradictory and mutually incompatible things. The pluckable straw to be discerned in the thicket of her emoting, the phrase suggesting — just possibly — that there might not have been any contradiction, is this one: ‘Ireland is a cruel country in which to be pregnant.’ She was right — but almost no one, on either side of the abortion argument, seemed prepared to open the box of how to become less cruel rather than extend that cruelty into the genocide that it threatens to become.

In her reference to the slaughter of the Somme, Nell hinted at her sense of a necessary complexity arising, perhaps, from a wider sense of culpability: who, when all is accounted for, truly contributes to sending children to their deaths? Is there not a responsibility falling on all the members of a society to make Ireland, at least, a place where bearing a new life will always be a joyous thing? A fair question. But we need first of all to agree that the slaughter is wrong, and then, each of us, Nell included, need to decide what our individual contributions might be to stopping it.

I wrote to Nell after the Ballybunion story broke to say that what she said first about abortion and the baby’s fingers and the bloodshed of the Somme struck me as the deepest, truest part of her public reflection, and that it spoke many times more loudly and clearly than what she said immediately afterwards to seemingly contradict herself and send those who thought they were following into either relief or deeper bewilderment.

Nell has not replied, but that’s fine, that’s the way we have often been, because we have tended to write to one another at moments of extremity in personal matters, rather than to talk about public affairs. Moreover, that email of mine might have been written to half of Ireland as readily as to its greatest feminist icon. And what it said, between the lines, was something like this: I see you now, Nell, your hour come round at last, slouching towards Bethlehem to be born into the truth that you already know, because otherwise you would not be saying these things at all, would not be wavering and vacillating and seeking affirmation from the public square of the country you have graced for half a century with your rough words of truth, this time in search of affirmation or clarity. It said something like: Surely some revelation is at hand, because it’s time to get real, as we all need to do before it’s too late; to face the full truth, not just a part of it; break free of the half-truths and disordered thinking and euphemisms, that have led us to this present appalling moment, when we stand possibly poised to become the first people in the world to vote for the annihilation of a section of itself, and not a once-off annihilation, but one that would continue into the unimaginable mists of the future, slaughtering our children’s children, and their children in turn, for the next twenty centuries of stony sleep. Anarchy loosed upon the world. Is this what we want? Because that’s what we’ll get.

The confusion that Nell articulated so truthfully and powerfully is not a random or accidental phenomenon. It is the product, of a culture in which evasion of the truth has for a long time been a standard reflex in many matters, but especially matters of the most intimate kind. There are many conversations we need to have, but, as Nell has intimated, nowadays we are even less capable than ever of having them.

How, then, did we get to this? How could it happen that we ended up having ‘debates' about something so obvious, so unthinkable, as to whether or not it’s okay to kill babies, making the idea debatable only by the device of rendering the baby invisible, inaudible and without defence, hidden away behind banks of clichés and tropes and mantras: ‘right to choose’, but no mention of who gets to choose and what is to be chosen; ‘abortion care’; ‘reproductive rights’ . . .

And I was thinking, too, about the words Nell recalled her mother saying: ‘That was no bunch of cells, Nell. That was my baby, four months old.’

I have long felt — and have written more than once — that the biggest obstacle in the line-of-sight between the average interested person and the unborn baby is not a physical impediment but the ostensibly harmless concept of the birth-date. If our culture did not make such a fuss of birthdays, but instead traced the origin of each person back to the true beginning — the shrewdly estimated moment of conception — there could be no tolerance of abortion. We would issue papers to each human person from the day of his first ultrasound, backdating her existence to the approximate date of conception, and that would be both the beginning and the end of it. No room for manoeuvre or obfuscation; no room for confused thinking.

The so-called ‘abortion debate’ provides a classic example of what, thanks to the illiberal liberalism that now dominates us, our political culture has come to: a constant wash of propaganda enabling a process characterised by official mendacity and rigged procedures, all designed to normalise the unthinkable thing that Nell described so vividly in Ballybunion. We did it by attacking thought and reason — by, as Nell herself intimated, destroying our own capacity for conversation.

That wash of propaganda has worked off the elevation of an unspecified ‘choice' — which begins with the woman claiming it, but now, in these coming days and weeks of May 2018, shifts to the person who may be standing in the way of her supposed freedom, and that might be you. Increasingly, people do not want to be that person — to be interrogated as to the reasons why they might deny this woman the right to this freedom, and be unable to answer, because the answers, though irrefutable when spoken silently under your breath, have been beyond the reach of what passes for public reasoning for a long time. The result is that people retreat into themselves, away from the debate, emerging in public to sheepily repeat mantras given to them by others or the media, deciding the issue not by their own lights but according to some ill-defined ethic of ‘tolerance'.

This is deeper than a privatisation of beliefs: it's the anaesthetisation of belief, to be quickly followed by the atrophication of belief. I don't think it's exactly that people know abortion is morally wrong and support it anyway as that many people think that judging others is even more wrong than another person having an abortion, and their having an abortion has nothing to do with me anyway, at least if I can avert my gaze from the reality of it. Therefore I do not oppose or question their choice. The only ‘sin’, by this logic, is my judgment bearing down on others. One is judged only if one judges, and therefore only sins if one repudiates sin, or talks of killing or murder.

The other technique, to go along with the occlusion of the baby, is the constant insinuation that objecting to ‘abortion care’ is purely a reflex of religious crackpots. This too hits its mark. As a result, many of those who will vote Repeal will have no stake in the issue but will do so to avoid ‘imposing their Catholic ideas'. The logic is essentially this: abortion exists already; even if I/we stop this or that particular abortion happening in Ireland, it will happen in the UK; so nothing is gained by objecting or seeking to deny what here is called ‘freedom’. Even if I am troubled by the concept of sin, there is no sin here for me. In fact, I exercise tolerance, which according to the pope is something like a grace. If so many people are okay with this, how can I say it is wrong? Therefore I will not say it. Therefore it is not wrong. In fact, it may even be a good because at least I am not being judgemental. This is the morass we've arrived at, and which Nell captured with such confused and confusing clarity in Ballybunion.

The essential nature of the profound dysfunction abroad in our nation right now is that people's heads are full of thoughts that have no roots there — they were transplanted there and have neither grown nor been rejected. They are not adequate to the formulation of a full rationalisation or defence of the beliefs they imply to exist deeper down, but they serve to convince those who hold to them, and those who hear them, that they are real thoughts, the expression of the humanity of an autonomous human person.

But what is being attempted here — by the Government and other advocates of child-slaughter — is an edifice of illogic painted up to seem coherent, built with apparent solidity but actually employing a chaotic and deceptive use of load-bearing which, in our deeply corrupted culture of thought and discussion, passes muster as order and reason.

Listening to the arguments, it is often difficult to tell where the greater part of the weight is being placed, such is the deceptiveness of the techniques of weight-distribution and use of cultural constructs mixed in with legal-sounding principles that are really perversions of the true law. A similar process occurred in Roe v. Wade, the historic case which led to the legalisation of abortion in the United States, when the law concerning homicide was simply ducked around and bypassed and an edifice of pseudo-logic built upon the right to privacy. Here in Ireland in 2018, a culturally normalised sense of a ‘service’ called ‘abortion care’ (already available, we are reminded, in a nearby country with more forward-looking ideas, et cetera) is being used to bear a considerable part of the load of pseudo-logic, as also is an illusion of extending to women rights that they are currently being deprived of (health, bodily autonomy, et cetera) and likewise to doctors who are allegedly denied some necessary legal clarity to enable them to ‘protect and care for mothers’. Added to that is the buttress of a false opposition between the child and the mother in as much as this opposition is convenient to create a pretext for disabling the rights of the child to be protected at all.

There is very little else in the structure being proposed apart from these elements, but the impression is being given that the procedure of simply asking the people whether or not they wish to retain Article 40.3.3 will serve to reconcile and justify all such incongruences, when really the whole thing is an exercise in burying them. The question is dishonest on its face, precisely because it is a bloodless question. It has no mess or gore. It is cleansed of truth and horror, and instead has the appearance of being a merely technical proposal for redressing an imbalance. The construction of this pseudo-debate conceals that it has placed no weight on the matter of how the law against murder is to be elided, how the architects of the proposed obscenity are to get around the fact that capital punishment, even for the most serious crimes, has been forbidden by our Constitution for nearly two decades, or how the natural, inalienable and imprescriptible rights of the child are to be dismantled without even an honest and forthright attempt at a redrawing of these rights or the outlining of a constitutional or legal basis of any kind for their elimination. In other words, what is happening is not that the laws of Ireland are being changed to facilitate abortion; what is happening is that the issue of changing the laws is in effect being made to seem other than what it is.

Numerous sleights-of-hand have been perpetrated in order to make the structure appear coherent, legal, constitutional and, as Nell says, ‘necessary’, when in fact all that has occurred is a series of quite disconnected manoeuvres, creating the impression of pursuing a logical path from the current dispensation to some new and equally legal and legitimate understanding. Children will die but this will be written up as ‘compassion for women’.

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold. The result of all this is an utterly confused and disoriented population, which seems to suggest itself — from the political and ideological viewpoints of those pushing the abortion agenda — as the optimal state-of-affairs. Timidity and incoherence combine to — as Nell has described — prevent us from talking our way into these questions.

These conditions, together with her own history of activism with and on behalf of other women, may go a long way to explaining the befuddled message Nell put out in Ballybunion. Going back on a lifetime’s certainties is not a matter for a single afternoon. Perhaps, now into her 70s, Nell is beginning to think abut the bigger picture.

And of course, if these questions were properly addressed, it is quite obvious that nothing like this structure could be built at all. In such a better country, we would listen to Nell pronouncements in Ballybunion and not become swivel-headed with indecision. We would hear what she said and hear too what her heart was saying louder than anything else she said: that the killing of innocents is wrong, wrong, wrong, and that continuing our longtime sleepwalk of unreason will very soon bring us to a turning that, once taken, leads all the way back to Auschwitz.

And in the end that is the only choice any of us will face on May 25th: Auschwitz or Bethleham. Death or life. You decide.

********************

In 2008, I wrote about Nell in the Mail on Sunday:

People often assume there to be some kind of mutual hostility thing going on between myself and Nell McCafferty. I suppose it's because she's a feminist and I'm regarded as something of the opposite, whatever that might be. But I've always liked and got on with her. I get a kick out of meeting her, and, even the times we meet immediately after we've had a public ding-dong, she never seems to carry a resentment, or even remember, or else has filed our difference away in some remote pigeonhole so as not to get it entangled with actually existing reality.

I first met her in 1984, in Granard, following the death of teenager Ann Lovett after giving birth to a baby boy in a church graveyard. The boy died too and the Ann Lovett story became one of the seminal episodes of the moral civil war that convulsed Ireland in that turbulent decade. I was just starting out as a journalist and had gone to Granard without much enthusiasm, and there I ran into Nell who was writing for In Dublin magazine. Later, she wrote the Granard story up as she had written up so many other stories: with heart-scalding truthfulness and eloquent rage.

Nell was one of the people who made me want to be a journalist. Later we got to know each other better, when I became her Editor at In Dublin, and once we even did a couple of stints on the same bill as stand-up comedians. (Not a lot of people know that.) Rather than opponents, I see us like the two guys in that Rumi poem: 'And watch two men washing clothes. One makes dry clothes wet, the other makes wet clothes dry. They seem to be thwarting each other, but their work is a perfect harmony'.

I ran into her at the Royal Hibernian Academy opening last Monday evening. She was there, of course, because her much-publicised nude portrait by Daniel Mark Duffy was part of the exhibition. I went along because my friend and neighbour, Oisin Roche, had a painting in, an oil-on-canvas portrait of Krystein, the Polish chef from Harry's Cafe in Dun Laoghaire. I had heard a little of the furore over Nell's nude and had seen a tiny photo of it in one of the papers.

When I arrived I caught a glimpse of Nell in the room where her portrait was hanging, which immediately struck me as impossibly brave, not because of the kind of painting it is but because having people look from you to your portrait and back again is always a strange experience. The aforementioned Oisin Roche did a magnificent portrait of me last year (in which I remained fully dressed), which was shortlisted for the UK BT Portraits of the Year Award. Last June we all went to London for the opening night at the National Portrait Gallery in Leicester Square. There is something deeply weird about being in the presence, with other people, of a portrait of oneself. It inflicts a sense of nakedness, regardless of raiment. On that occasion I got offside as quickly as I decently could.

But Nell was sticking her ground, which took some bottle given the sheer ignorance you sometimes encounter in people. In the couple of minutes I spent standing in front of her painting, a woman behind me burst out laughing and screeched, within earshot of Nell, 'What does she think she's at?' I went over to Nell and said I thought her picture beautiful. In recognition of her bravery, I would have wanted to say something nice anyway, but I wasn't telling a white lie. I think Daniel Mark Duffy's picture is indeed beautiful, and here's why.

Nell McCafferty is a kind of guerilla fighter. She confronts the moment in whatever way she finds it, with whatever she has at her disposal. Her understanding of things is intuitive as well as intellectual, and she brings to every question the fullness of her own experience and soul. You might disagree with her about things, but I don't think it is possible to listen to her with an open heart and not identify with something deep in everything she says. Nell is real.

This painting is her saying something new, something that belongs to the way she is now, having recovered from a couple of health scares, in the year when her life's great love succumbed to cancer. Daniel's painting of Nell is better than a thousand books, because it is Nell being Nell. She looks as scary as ever. (And anyone who doesn't think Nell is scary has never faced her across a TV or radio studio.) But she is vulnerable, too, in the literal nakedness she has chosen to reveal. She is herself, at the age she is, in the condition you would, approximately, expect. She is human, fragile, ageing, perhaps a little frightened. But she is beautiful, too, an echo of the mystery of creation, carrying with her a story about the integrity of life from start to finish, of a doughty advocate whose physicality has forged with her personality into a single, pure beauty.

There has been some critical commentary about Nell's decision to do this picture — some of it, interestingly, from those who would count themselves her ideological allies. They say that, having for years railed against the objectification of the female form in advertising and the media, she has betrayed her misson as a feminist by exposing herself in this way. Nell has responded by asking what kinds of cars people imagine she will be called upon to drape herself over in the marketplace. 'What would I sell?', she asks. 'Trabants?'

I don't think they get it. This is not to do with the exploitation of the female form, but about confronting the view of the human body our culture imposes as we grow older. Each of us stands in front of a whole life, from the moment of creation to the moment of death, with nothing but perhaps a sweeping brush to sweep the street in front of that life. We live in a culture that dishonours this reality, proposing every moment an ideal which any of us is, at best, capable of resembling for a mere cosmic instant. As a result, among many baneful consequences, the very essences on which human societies depend for their survival — experience, wisdom, tradition –—are sidelined in a culture that cannot look squarely at things bearing the wrinkles and blemishes of age for fear of being infected with the condition that must at all costs be denied. The result is a feeling transmitted like a virus to each of us, whispering that we belong to the fullness of reality for one brief flowering, and afterwards must shuffle away towards obsolescence.

There is a beauty that grows with age, but which can be seen only in the totality of a human being, in the essential dignity that comes of having lived and loved and survived some stuff. This is what makes the world safer than it would otherwise be.

This, I apprehend, is what Nell is now telling us, as in the past she has told us other things we could not hear for some time. She hasn't put it exactly as I have, but close enough. The trouble is she risks being judged by the values of the sick culture she seeks to heal. Presenting an image that at once parodies and subverts the conventional images of naked females, she sets off two reactions — the one she intends, yes, but also the one the culture has become conditioned to. And the latter is what made that ignorant woman behind me laugh out loud.

************************

My relationship with Nell was as one person to another — not so much one journalist to another, as she was as suspicious of journalistic culture as I was. She was never a foot-in-the-door merchant; she didn’t need to be: she was Nell.

She was, or used to be, a central figure in Irish culture, until something happened — or a series of somethings — that caused this to, if not end, certainly to tail off prematurely into uncertainty. She said something on the radio about a female politician, and a libel case ensued, which made the media irrationally wary of her. Before, she had been on the media even more than I was, which is saying something; afterwards, not so much. Then there was the matter of her constant desire to adopt waifs and strays, which got her into trouble by virtue of her tendency to accompany her kindnesses with brief expositions of the truth. One such individual, a singer of popular songs, became sufficiently enraged by Nell’s truth-telling as to call up the Editor of a publication she wrote a regular column for, and demand that she be fired. Nell told me that, in terminating her contract, the Editor ‘explained’ that one picture of this individual on the front cover of the implicated publication sold more copies than years of Nell’s columns. Sisterly solidarity in the new ‘progressive’ Ireland!

Nell was one complex lady, but a lady is what she was, though her manner could be sometimes abrupt and even grumpy. She would lecture you in the act of helping or consoling you: You use too many adjectives, some of them puerile, about psychiatric care and about the media. That is bad for your writing, and i will just presume that you are venting.

About ten years ago, I had her listed for inclusion in 50 More Feckers, a proposed follow-up to my 2010 book, 50 People Who Fecked-up Ireland. It was supposed to be published in 2015, but was aborted as a result of my cancellation.

The idea behind the books was not to slag people off (not always anyway!); sometimes the focus would to highlight some strength in the person which had backfired because of some involution in the culture. Her citation would have related to her inability to slough off the cast of feminist, when in fact she was, first and foremost, an Irishwoman in a long tradition of Irishwomen, speaking about Irish affairs, and Irish emotions, and Irish ways, good and bad of them.

Incidentally, in February 2014, in the middle of that cancellation episode (arising from an assault from the LGBTPQ goon squads), she sent me this tentative email:

how are you doing, John? nell

I replied, with equal economy:

Thanks for the text. Slings and stones and sticks and arrows . . . You know yourself.

A few days later, having thought about it, I wrote:

Nell

That response I sent the other day was guarded and inadequate. I've been getting a lot of stuff, some of it from fake addresses of real people (to draw me out, I presume), and [not recognising the email address] couldn't be sure it was you. . . . I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart for that simple question. I'm ok. Still here.

Thank you.

John

She replied:

Tell them everything. It confuses them.

Imagine such an exchange between Ireland’s best-known lesbian and its allegedly most notorious homophobe. Signs of the times that were a-coming.

She could be gossipy, even indiscreet, but never in our dealings betrayed a vital trust. Before letting loose with some such minor indiscretion, she would preface:

In total confidence — don’t be insulted by the caution . . .

Behind it all, she was kind and decent and immensely funny. She was self-deflating to an extent I would describes as virtually unique. Ah, jaysus, as you see, i haven’t quite relinquished my role of God.

If I was not so keen on avoiding cliches like the plague, I’d say she had a heart of gold. But terms like ‘compassion’ and ‘humanity’ have been so trampled underfoot by hypocrites for too long to be appropriately applied to Nell. What she had was empathy — and not just for women, about whom she was, in general, far from naive. This was her great strength as a writer. She had what, mindful of the scientific dubiousness of the concept, I would guardedly call a vast emotional intelligence. She believed in helping people, not just pretending to, which she called ‘love from a distance’. She once wrote to me: My eventual death notice in the deaths column of a paper will carry the warning — no emoji’s, or empowering hugs from a distance — but the current Irish Times would probably censor it as inappropriate.

There were times when we were in touch more than was usual. She was aware of my personal facts and circumstances in fighting to retain an involvement in my daughter’s life. She never said she was sympathetic; she just was. Without my confiding in her, she intuited the general picture, which I have never spoken about publicly in it particularities. We would exchange emails in which she would advise me, sometimes caution me to relax in one way or another. Her instincts were generally good. She was the only public figure I encountered who grasped what was at stake. And in this she had clear sympathy not just with me, but with all the parties concerned.

At a particularly appalling moment in our story, she wrote to me:

Apologies for intruding again, john. If it is of any comfort, be assured that i will defend you and Roisin, no matter what happens. i can be very good at that kind of thing.

Much love, truly

God Nell

In the days since she died, people I know and like and respect have been sending me sardonic message about her, assuming that they will find favour. They haven’t. I liked her enormously. I trusted her. She never betrayed me. She simply wasn’t what they thought. That was a caricature. Nell was real.

To buy John a beverage, click here

If you are not a full subscriber but would like to support my work on Unchained with a small donation, please click on the ‘Buy John a beverage’ link above.