Natural Law — a short series, Part 1/3

The natural-law tradition has for centuries been the guiding light of Western civilisation, but human cleverality has recently conspired to jettison it, because it is said to offend against modernity.

Statute of the Heart

There has, it seems indisputable, been a dearth of discussion of a particular aspect of the mass overnight defenestration of fundamental rights by Western governments in the spring of 2020. This relates to the basis on which the suspensions of constitutions and the abrogation of rights conventions and charters could have been effected, given that many of the affected rights were in the relevant documents characterised as, if not totally absolute, then certainly more robust than a minor respiratory ailment ought to have been capable of striking down. The language of many of the affirmations and guarantees of these rights, with their use of words like ‘inalienable’, ‘indefeasible’, ‘antecedent’ and imprescriptible’, is such as to suggest them as capable of withstanding more than an unsubstantiated declaration of a global pandemic by an unelected supranational body. Moreover, one might have expected that, even if the courts systems of the various affected jurisdictions were not themselves in a position to unilaterally intervene in order to carry out their primary function of protecting such rights – and by extension the conventions, charters and constitutions — they would, at the very least, have been moved to expedite and support any action by a citizen seeking to have the legality of these abrogations scrutinised and, if found wanting for justice, struck down as unlawful and earmarked for watchfulness as to the possibility of repetition.

The contrary tended to occur. Wherever actions were initiated, especially in cases taken at an early stage and seeking a wide-ranging examination of the rights-abrogations involved, applicants found themselves subjected to a circular form of judicial reasoning on the proffered basis that, since there was in train a ‘deadly pandemic’, governments were justified in whatever steps they might have taken. Universally, in all but a tiny minority of cases, attempts to have the Covid ‘measures’ subjected to judicial review were rejected out of hand, with only cases involving peripheral issues of personal grievance seeming to attract the sympathy of alleged judicial watchdogs of human freedoms.

A significant factor in these phenomena, undoubtedly, was the essentially political nature of the implicated legal systems. Judges in many jurisdictions are political appointees and, even where they are not, the judiciaries are — protestations of independence notwithstanding — tightly bound-up with the executive branches of government. The confused and contradictory doctrine of the separation of powers is generally sufficient for judges to see their function as to repel any significant challenge to the actions of government, at least until the dust of the instant crisis has time to clear.

But there is a deeper factor, which has to do with the antecedent underpinnings of fundamental human rights and freedoms as expressed in constitutions, charters, conventions, and bills of rights. The longtime understanding in Western civilisation has been that these rights are not ‘manmade’ in the sense of having evolved purely from the unaided genius of humanity; they are given. Immediately a primed alarm, installed in secular society to defend itself from ‘superstitious’ ideas, goes off: Even where our most basic freedoms are concerned, it seems, it is thought more urgent to continue eschewing alleged hocus pocus than pay attention to what the real conjurers are doing. It is not necessary to know or decide by whom or what things are ‘given’ in order to comprehend that our fundamental rights amount to ‘gifts’ as much as does life itself. All that requires to be understood to this end is that, in order for humanity to formulate principles of right, wrong, truth and lies, it has needed to look into the experience of its own species in the world in order to, yes, divine the immutable patterns that have revealed themselves through time and history.

While these stood as at least functional understandings, and — moreover — while they continued to lie undisturbed within the foundations of our civilisation, they acted as bulwarks against tyrannical incursions by opportunistic power-seekers. The original problem that intruded to render possible what has now happened was that the principles and schema underlying these safeguards and protections came to be regarded as out of date. Indeed, looking back now, three years after the most comprehensive rights-grab in the history of Western civilisation, it is possible to observe a long-term period of preparation that brought us — inexorably, it must now be observed — to the unprecedented conditions that confronted us three years ago.

The core, unspoken problem that enabled the events of the spring of 2020 was that the freedom documents of our civilisation had already been disabled by virtue of the siphoning-off of the stiffening substance that had enabled them to cohere and remain impervious to attack. This substance is known as ‘natural law’, a phenomena generally — if somewhat misleadingly — identified exclusively with religious morality, though once the very bedrock of our legal systems.

The concern of these articles is not — at least in their focus — ‘theological’. The context of their concern is that vital things are being lost due to ‘theology’ and ‘religion’ having become separated from the mainstream of social and cultural reality, leading to the diminution and incremental confiscation of certain fundamental rights of man. This has been enabled by a form of sleight-of-hand effected by secular authorities in using the dissenter’s objection to religious/sectarian encroachment on the State and ‘private’ morality as a cloak to cover the theft of the most fundamental understanding in natural law: that man has a priori rights that are not rightfully in the preserve — or, indeed, gift — of political or other secular authorities.

In other words, the problem we address arises from the post-Enlightenment separation of the religious from the socio-political and profane worlds. It is, precisely, that a tug-o-war, insinuated though undeclared, between the people and the state in the modern democracies, seems to have now resulted in the stripping of the democratic and hitherto sovereign power of the people and its transfer and vesting, as though things had always been so, in the state. A large part of this process is that ideas concerning the most rudimentary criteria of free societies are incrementally and uncontroversially being sequestered by political authorities on the spurious basis that these concepts and principles were first formulated in ‘religious’ contexts, so that such secular authorities are able to assert — and gain media and public support for such assertion — that these alleged principles are mere arbitrary ‘moralistic’ impositions of a primitive and religious past, and ‘have no place in a modern society’.

There are many interesting ‘theological’ arguments still to be had about natural law as it manifests within the sphere of religion and of everyday human existence, but the point of these articles is not to add to them. Rather, the purpose is to draw attention to a drift in the public affairs of Western civilisation that, in appearing to be ‘progressive’, is actually quite the opposite, and that, in purporting to expand the liberal order, modern political establishments are now attacking the very bedrock of human freedoms, and succeeding in a piecemeal claiming for political authority of the right to interfere in human existence at the most elemental and intimate levels.

The trick employed by secular-political authorities might be compared to the shyster tradesman who offers gratis to take your redundant copper pipes to the landfill, with the intention of more than matching his wages by selling them off. This is the endgame of a long history of propaganda and misdirection, in which ideas inconvenient to the emerging forms of neo-authoritarianism have been strategically contaminated by public prejudice, by or on behalf of interests seeking precisely the curtailment of human freedom.

Many of the freedoms we have enjoyed in Western civilisation have been bequeathed us — in a language and logic that belong to transcendent concepts of reality — by a history in which religion was not a separate element of culture, but the very portal through which humanity looked in order to divine the meanings of reality. In The End of the Modern World, Roman Guardini wrote that the Middle Ages were ‘filled with a sense of religion that was as deep as it was rich, as strong as it was delicate, as firm in its grasp of principles as it was original and fertile in their concrete expression.’ Religious thought was concerned with ‘the good’ — the good of humankind, divined from observation, experience, trial and error. Customs and laws evolved to venerate and maintain the understandings that were found to optimise human peace and happiness. In this formulation, it becomes clearer that what we speak of are not especially ‘religious’ understandings, but ones that belong at the centre of the public square, including the public square of ‘modern’ society. Contrary to the prejudices of the moment, the characteristics that distinguished the era Guardini was writing of from the mid-twentieth century of his writing, or indeed the present time, was not its backwardness or obscurantism, but the fact that its normative viewfinder, incorporating capacities directed at both the ‘religious’ and ‘secular’ realities, was capable of taking in — in theory and principle — the whole of reality, and was therefore far better equipped to comprehend the human structure than the thought systems and ideologies of the supposedly ‘modern’ societies of the present. By embracing both science and the mysterious, the known and the unknowable, the devices of apprehension in use at that time were far less limiting of human self-understanding than the hyper-communicative technologies of 2023 — and precisely because they placed no boundaries between the religious and the real, the secular and the sacred, the holy and the profane. We are given to believe that many of the assumptions and inferences effected in those times were necessarily partial, speculative and, in retrospect, primitive understandings of how reality works, and that these defects arose chiefly from the narrowness of religious outlooks of the time. This is a foolish error. In casting these alleged misunderstandings away, we throw out also much that, far from being discredited or surpassed by more recent understandings, remains in the foundations of our civilisation, to the extent that these survive. We need to awaken rapidly to the realisation that, in the guise of ‘modernisation’, many of the foundational ideas of that civilisation are being jackhammered and carted away. Foremost among the ‘condemned’ phenomena is natural law.

This term — ‘natural law’ — is used to summon up a body of ethical imperatives said to be inherent in human beings and discoverable by human reason. It therefore differs from statute law and common law (although much of the latter derives from natural law) — and even from supernaturally revealed ‘divine law’. Natural law is actually, at its root, a philosophical rather than a theological construct. To grasp the concept, it may be better to approach the matter from a desire to understand what natural law pits itself against. At its core it is a rejection of any idea that the laws we are enjoined to follow have or could have arisen from subjectivity, pragmatism, power, utilitarianism, arbitrariness or evolution. It asserts that, universally, human beings share a set of ethical norms not so much based on ‘revealed’ truth as the truth ‘written on the human heart’ — amounting to a body of binding norms rooted in shared ‘natural’ understandings as to the structure and mode of propulsion of mankind, and the correct manners of behaviour congruent with this.

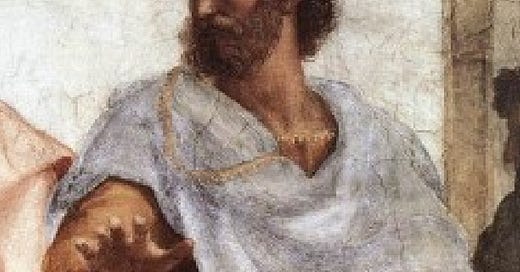

In Written on the Heart, his 1998 book about the origins and nature of natural law, the American philosopher and theologian, J. Budziszewski, traces the theory of natural law back to its original sources, including Aristotle (pictured above), Thomas Aquinas and John Locke.

‘For Aristotle,’ he writes, ‘the great natural-right philosopher of pagan antiquity, begin with the Nicomachean Ethics — named after his son, Nicomachus. Then turn to the Politics. This work of Aristotle foreshadows the natural-law tradition; he recognises an objective standard of right and wrong, even though he does not fully grasp that it is law.’ Aristotle, being fixated on the ‘nature of the good’, insisted that ethics are indispensable for understanding politics and human partnership in a good life, which is the object of the City, his concept of the most comprehensive locus of that partnership. These ethics, he said, are what distinguishes the City from a gang of thieves, for otherwise there is nothing but naked power. In the City, we are drawn together in mutuality, the necessary state of the good life. Only in the City do the necessary mutualities of the human condition acquire the capacity to be governed by justice under law. In the City, man pursues the highest good, the greatest good. The pursuit of this is something internal to — built into — the human heart and mind. This transcends subjectivity and relativism, however, only when it becomes a quest for what transfixes mankind in general, .i.e. a universally-directed journeying via the common opinion of mankind to the common truth about mankind’s condition and situation. The greatest good of mankind, Aristotle concluded, was happiness, a concept that presents obvious definitional problems. Happiness arises out of several diverse elements: pleasure, honour, virtue, excellence, as well as bodily goods such as health, and external goods such as wealth. How are these sometimes contradictory concepts to be reconciled and condensed into a single understanding? We need, says Budziszewski, to separate the wheat from the chaff, and this is something our minds are constructed to do. Happiness consists in something abiding, not transitory, even though the relevant transitory experience (pleasure, for example) may be an ingredient of happiness. Similarly, a man desires honour, but even more to merit honour, an honour that cannot be taken away. Similarly virtue, which like honour is at once necessary and insufficient for happiness. The conditions of honour and virtue come with what Aristotle calls ‘equipment’, which includes body and external goods. The virtue of generosity, for example, is no use without something to give. The good resides in doing what we are here to do, which itself implies some purpose or meaning for our existence. The greatest good, therefore, consists in carrying out this role or function to the best of our ability — so the function of a human soul will be ‘whatever a human soul can do that nothing else can do, or at least that nothing else can do as well.’ Here, we trip across the ‘unique selling point’ of the human: its capacity for rational thought and reflection. The human soul is an engine for coming to reasonable conclusions and acting upon them. This capacity is what unites all the other human attributes and creates the potential for true happiness, the 'greatest good.’

This thread of Aristotlean reasoning represents the bedrock of the natural law. Many others have added to the store, but all have been working on Aristotle’s foundation. Budziszewski, for example, cites an analogy coined by C.S. Lewis, directed at the question of bringing the human soul under the direction of reason — the marshalling of thought — based on Aristotle’s reflections on human partnership and the City. The analogy is of a fleet of ships sailing in formation. For the voyage to be successful, the ships must avoid collision or getting in each other’s way, while at the same time each individual ship must be seaworthy, its engines and sails in good order, and all ships must know the fleet’s ultimate destination. Morality, Lewis deduced, seems to be concerned with three things: with fair play and harmony between individuals; with what might be called tidying up or harmonising things inside each individual; and with the general purpose of human life as a whole: ‘what man was made for; what course the whole fleet ought to be on; what time the conductor of the band wants it to play.’ These requirements/criteria, Budziszewski points out, correspond to the virtues concerned with harmony, courage and wisdom. Bringing the human soul under the direction of reason requires also the marshalling of feelings and desires. A City — society — needs to operate to these laws just as much as an individual. This, really, is the purpose and meaning of natural law.

For Thomas Aquinas, the Roman Catholic systemiser of Christian natural-law theory, Budziszewski urges us to study the Treatise on Law, which makes up a small part of the Summa Theologica. Afterwards, he says, spend some time with the Treatise on Kingship. According to Aquinas, the correct perception of the natural law requires an understanding of nature as designed to particular purposes. Budziszewski writes: ‘The way Saint Thomas put this was to say that the “nature” of any particular thing is “a purpose, implanted by the Divine Art, that is to be moved to a determinate end.” Provided that we haven’t been taught not to, this is the way we tend to think of things anyway. An acorn is not essentially something small with a point at one end and a cap on the other; it is something aimed at being an oak. A boy in my neighbourhood is not essentially something with baggy pants and a foul mouth; he is something aimed at being a man. In this way of thinking, everything in Creation is a wannabe. We just have to recognise what it naturally wants to be. Natural law turns out to be the developmental spec sheet, the guide for getting there. For the acorn, nature isn’t law in the strictest sense, because law must be addressed to an intelligent being capable of choice. For the boy though it is. The acorn can’t be in conflict with itself. He can.’

In his 2011 book, Natural Law and Natural Rights, John Finnis elaborates that a theory of natural law ‘claims to be able to identify conditions and principles of practical right-mindedness, of good and proper order among persons, and in individual conduct.’ Accordingly, he argues: ‘Unless some such claim is justified, analytical jurisprudence in particular and (at least the major part of) all the social sciences in general can have no critically justified criteria for the formation of general concepts, and must be content to be no more than manifestations of the various concepts peculiar to particular peoples and/or to the particular theorists who concern themselves with those people.’ This gives us some sense of the loss we may suffer from surrendering the foundational thought infrastructure of the natural law.

The principles of natural law, Finnis insists, ‘hold good’ just as the mathematical principles of accounting ‘hold good’. This idea is shared by many natural law philosophers and thinkers. In his 2005 book What We Can’t Not Know, J. Budziszewski offers the following definition of the logic of natural law: ‘However rude it may be these days to say so, there are many moral truths that we all really know — truths which a normal person is unable not to know. They are a universal possession, an emblem of rational mind, an heirloom of the family of man.’

This does not mean, he insists, that we were born knowing them, or that we don’t lose our nerve when told they are not true or not ours. We may not know them with unfailing clarity, or have thought them through. Believing in them does not mean that we do not pretend occasionally not to know them, or that we get confused about them.

‘Yet,’ he writes, ‘our common moral knowledge is as real as arithmetic, and probably just as plain.’

The objections raised to the natural law concept and tradition through time have been varied but have nevertheless converging around a particular concern of power. The most commonplace is that the natural law is ipso facto sectarian, or at least offensive to ‘pluralism’, because it appears to be, first and foremost, a creature of religion. The fact that natural law had originated in the pagan past of ancient Greece — a tradition otherwise venerated by liberals — and had for centuries been regarded as a universal code of rights and freedoms, did not serve to mitigate these complaints. It was claimed that the appeal of natural law to the Abrahamic religions was itself a reason that it be eliminated from the civic arena. At the heart of this argument was the idea that natural law had evolved from ‘revelation’ rather than logical reasoning, which overlooked that revelation was, in fact, at the heart of the process of reason, since one of its first principles in the ancient world had been that God — or ‘the gods’ — had made the world in a manner capable of being divined by mankind. This argument was therefore tautologous, but the evolving secular world, which managed to push religion into a corner on its own, was increasingly able to obscure this foundational reality. Moreover, the almost exclusive emphasis by the religions on questions of sexual morality did nothing to forestall this drift, since it gave purchase to the argument that the natural law was excessively concerned with a narrow band of morals in the intimate sphere, and rather less with the freedoms of human beings more generally. Thus, it became easier to insinuate the natural law as not so much a universal schema for rights enumeration as a binding programme of sensuality prohibition. Natural law collided grindingly with the crude evolutionary version of humanity’s origin, which made it easier to treat it as some kind of quaint relic from a naïve past, when really it was indeed a universal and open charter that just happened to be couched in a particular language and logic that belonged to a time when religion was a central viewfinder of both politics and science.

One of the early objectors to natural law theory was the late nineteenth century English philosopher John Stuart Mill, himself an atheist. Mill’s objection was essentially that principles of natural law, being framed as ‘abstract doctrines of morality’, were too vague and generalised to be of use in framing particularised laws directed at specific individuals and concrete situations. But this argument, though certainly valid in the context of religious preaching, where great emphasis would be placed on winning over to righteousness the individual conscience, did not speak to the tabulations of absolute rights and freedoms that had emerged out of the same formulations. It was true that natural law rights and freedoms tended to be expressed as principles, but this was precisely their great strength and virtue: to allow the general to be particularised on the basis of non-negotiable premises.

Others of the objections were more disingenuous, for really the purpose was to wrest control of law-making back from the grip of history, which had tied the hands of ‘modern’ legislators by setting down a comprehensive and hermetically-sealed programme of rights and freedoms that did not lend itself to editing or radical amendment.

Thus, the early attacks on natural law arose in the context of purported attempts by power establishments to get the clerics out of people’s bedrooms, although, once the precedent was established, these were followed hard by a more generalised liberty-taking by politicians and judges. This may be why the United States has perhaps most successfully — until quite recently — managed to maintain its strong tradition of individual rights based on ‘self-evident’ truths: because it was clear that these principles were couched and cherished in philosophical terms. Nations where the religious emphasis was foremost tended to fold more rapidly. Opposition to religious influence has been one of the chief avenues of attack on Western civilisation by Cultural Marxism, whose proponents sought to rebuild the entire edifice of human rights from the beginning, forging power for themselves and their sponsors by representing and elevating the underdogs of history who were to be furnished with new and compensatory ‘rights’, which in turn could be weaponised to gain power over systems and territories.

Up until the 1940s, the influence of Enlightenment cultural revision had minimal effects on the law, in which the absolutes and quasi-absolutes of natural law were held, yes, sacred. In 1937, for example, a new Irish Constitution — still in operation today — was deeply embedded in natural law, in particular in respect of fundamental and personal rights, set out in Articles 40-44. In the post-World War II period, the emerging universal trend — purportedly in pursuit of unity and non-confrontation — was to seek a lowest common denominator ‘pluralism’ between different traditions and cultures, which resulted in a changed attitude to natural law philosophy that increasingly bemoaned the influence of revelation and theology, leading inexorably to the dismantling of the structure of bedrock principles that underpinned our legal systems, our democracies, and our free societies.

The Irish Constitution provides a textbook case of a rights and freedoms charter that has been eviscerated over the past 25 years by a series of attacks from governing politicians and establishment figures more generally, using quasi-democratic instruments like referendums and ‘citizens assemblies’ to essentially disable its key protections so that the government of the moment can do just about anything it pleases without fear of being called to book from the judicial bench. Indeed, the judges have been conducting their own separate campaign to disable the most fundamental rights referenced in the constitutional text, as we shall see in Part II of this short series. In all cases, the targeted articles have been ones that we might have imagined to be reinforced to the point of indestructibility by the solidifying power of natural law residues.

In the referendums of 2012 (‘Children’s Rights Referendum’) and 2018 (‘Marriage Referendum), a few of us fighting to defend the Constitution divined that, above and beyond the instant issues being pursued, we were witnessing strategic attacks on the fundamental rights of families in a manner that was actually unlawful, unconstitutional, and profoundly dangerous. In effect, in those referendums, the Irish government performed two sleights-of-hand, both times convincing the public that it had a right to vote on matters that were actually beyond the remit of Government and People. Both of the targeted articles had made clear that the rights set out within them were not extended or generated by the state, but were ‘antecedent’ and simply ‘recognised’ within the constitutional text. Thus, Article 41 begins, ‘The State recognises the Family as the natural primary and fundamental unit group of Society . . . ’; Article 42 begins, ‘The State acknowledges that the primary and natural educator of the child is the Family . . . ’ (my emphases).

The rights inherent in Article 40-44 include the right to life, equality before the law, reputation, property, to the inviolability of one’s home, to practice one’s religion, to habeas corpus procedures, to freedom of expression, to public assembly, to form associations and unions, to the protection of family life, to education, and also a number of unenumerated rights, including the right to bodily integrity and recognition for the dignity of the person, the right to earn a livelihood, to privacy, to communicate, to have access to justice and fair procedures, to travel within and outside the State, and potentially many others as yet unidentified. All of these rights derive from the natural-law tradition, and should rightly be regarded and treated as the inalienable possessions of the Irish People, whether we had a constitution or not.

It is absolutely clear from what John Finnis has to say about absolute rights (see below), from the language in the constitutional provisions themselves, and from the history of the framing of that document, that there could never be any basis whereby fundamental rights and freedoms could be abridged in the manner in which they were suspended in the package of legislation enacted by the Oireachtas (parliament) and signed by the President of Ireland three years ago. It is clear, also, since the situation then facing the government did not meet the criteria of Article 28.3.3° — which requires conditions of ‘war or armed rebellion’ to justify the declaration of a State of Emergency — the effective suspension of the Constitution effected by the caretaker Irish government of March 2020 (a hangover administration that had been booted out by the electorate a month earlier) was unlawful on its face. As I wrote in another article recently, that caretaker government had no authority to concoct the package of legislation it produced to deal with the claimed Covid emergency, without firstly persuading the people to modify Article 28.3.3° in accordance with its characterisation of the situation requiring this change.

Moreover, it is my contention that the situation facing the caretaker government in March 2020 was in no way comparable in gravity to that obtaining in 1939, when the present version of Article 28.3.3° was enacted, and yet the government’s arrogation to itself of powers was way in excess of what was contemplated or implemented on that occasion. The Covid package, moreover, was introduced with a minimum of concern for constitutional principles, parliamentary procedures or adequate democratic debate. The State lawyer’s later declared that their client had not availed of Article 28.3.3°, and did not declare a State of Emergency, a claim that is risible and hubristic, since the word ‘emergency’ punctuates the legislative text, albeit with a lower-case ‘e’. Was it being suggested that, by a simple typographical trick, it became possible to bypass the sole provision for the suspension of the Constitution to enable an State of Emergency to be declared, and in doing so augment and indeed multiply the powers available via that sole article by simply eliding it? The government/state appeared to be claiming, in effect, an entitlement to declare an emergency with a small ‘e’, thus magically acquiring the right to behave as though Article 28.3.3° did not exist, and in the process behaving as if the Constitution of Ireland was amenable to abrogation at the drop of a hat, with the nullifying of any and all of the protections set down within it.

The question as to whether it is possible for a government to declare an emergency outside of Article 28.3.3° — an emergency with a small ‘e’ — is dealt with briefly in Ireland’s premier legal textbook, J.M. Kelly’s The Irish Constitution.

He states:

The case of actual invasion is dealt with by Article 28.3.2; but other emergencies can be imagined which might require executive reaction going beyond the spheres of commodity supply and control of wireless communications, and also beyond the specialised powers of the police in regard to traffic control. Common sense dictates that in the context of a natural disaster, epidemic, escape of wild animals or dangerous prisoners, etc. the police, or informal auxiliaries, should not be faulted for evacuating streets, commandeering vehicles, or possibly in some cases placing persons under restraint of some kind; one could argue that there is a general right and duty, in any government, by common law, to protect its people as well as its own authority. But where the frontiers of this licence might be drawn — at what point might the authorities be regarded as having abrogated constitutional rights — and what conditions would justify its exercise is hard to say. The simplest framework in which to envisage the problem is that in which the State is in the defendant posture in the suit of someone aggrieved at being subjected to arbitrary compulsion, and in which the States raises the pleas of necessity. Whether this is a good defence, and what would distinguish it from the illegal pretence of ‘act of State’, are matters which have never been considered by an Irish court. In Ryan v. Ireland, 1989, however, the Supreme Court took the view that Article 28.3.3 precluded, by implication, the operation of common law doctrines arising from the necessity to ensure the safety of the State during a period of war or armed rebellion, and which have the effect of abrogating constitutional rights. While this does not directly cover the point at issue — the existence and extent of the State’s powers to act in some sudden or unusual contingency not envisaged in Article 28.3.3 — it might indicate a reluctance on the part of the judiciary to accept that the State has residual coercive powers over and beyond those provided for by constitutional and statute law.’

It might indeed. In the circumstance with which the caretaker government was faced in March 2020, then, Article 28.3.3° represented the sole route by which a State of Emergency might have been declared while abiding by the Constitution, and any constitutional process of otherwise effecting such a declaration would ipso facto have involved adding a new amendment to the Constitution, as occurred in 1939. It is unclear if or upon what grounds this was deemed by the caretaker government to be unnecessary (the question has never been asked in the Oireachtas). In the event, it was decided to ride roughshod over the constitutional rights of citizens by raising up an entirely new, extra-constitutional edifice, which, being constructed on existing statute law that in no way offended against the Constitution, sought by a sleight-of-hand to avail of the deliberate, misdirecting impression that the added, amending sections were themselves constitutional. In truth, these sections contravened the Constitution in ways not remotely envisaged by its framers in 1937, most likely because those good men would not, in their wildest nightmares, have imagined that any legislator would in the future attempt such a cavalier and irresponsible endeavour.

The State repeatedly claimed in court, in the hearings prompted by the challenge submitted by Gemma O’Doherty and me, that it had ‘never been suggested’ that Article 28.3.3° had been invoked or that the measures adopted — the ones being challenged by us — were covered by Article 28.3.3° immunity. ‘The Respondents have never disputed, and do not dispute,’ their counsel told the court, ‘that the measures adopted are subject to the general provisions of the Constitution.’ There is a strange paradox at the heart of this claim. In relying upon the elision of Article 28.3.3° in declaring this ‘non-Emergency emergency’ to claim even greater and more extensive powers than might have been available to it even under that provision, the State seemed to treat the Constitution as though it were a facilitator of state tyranny, rather than a deliberately constructed impediment to it. One clear implication of this move would be the farcical notion that Article 28.3.3° was intended as a blueprint for coping with a single possible eventuality among many, as though by way of an example — i.e. ‘war or armed rebellion’ — rather than an exclusionary principle designed to confine the reach of state power. The logic of the state’s defence is that the manner in which the article was framed and couched has nothing to say to the handling of other ‘emergencies’, which, it is implied, are somehow covered elsewhere in some vague enumerated fashion, though no explanation is offered for why, then, it should have been necessary to deal with the context of ‘war or armed rebellion’ on its own. Why would the framers have done this? No answer comes back from the perpetrators of this outrage. The answer is that the framers expressly ruled this possibility out of the question.

The implications of these 2020 governmental arrogations from a constitutional perspective are staggering in multiple senses. They include the implicit proposition that the Constitution of Ireland, in its 83 years prior history of existence, had lain in plain sight not as a charter of rights and freedoms but as a blueprint for totalitarian despotism. They include also the clear implication that there is no necessity, in the context of any set of circumstances adjudged by the Government, the Oireachtas and the President to amount to unusual or special circumstances in respect of public order, health, weather, or indeed in any circumstances whatever, with pretext or without, to declare a State of Emergency under Article 28.3.3°, in order to suspend or void the rights and freedoms of Irish citizens. It means that the rights and freedoms hitherto presumed to be contained in the Constitution of Ireland, and presumed for the previous 83 years to have had the meanings capable of being ascribed to them by means of the ordinary and everyday interpretations of words in the Irish and English languages, were in fact not the assertions of rights or freedoms at all but coded messages to would-be tyrants that, in constitutional fact, the citizens of Ireland were mere serfs and chattels, to be imprisoned at the whim of authority.

All this is a downstream consequence of the piecemeal historical onslaught on the legitimacy and reach of natural law within the edifice of the Constitution. The caretaker government, in a situation of zero opposition, parliamentary or otherwise, permitted itself to ignore the language of the constitutional text and decide that it was possible under the Constitution of Ireland to enact legislation and/or statutory instruments which permitted State actors to invoke inter alia the following entitlements, this list being merely illustrative and not exhaustive:

To incarcerate citizens in their own homes;

To prevent citizens, at any time and for no particular stated reason, travelling farther than a stipulated distance from their homes;

To summarily close down businesses, trading premises, parks, scenic areas, beaches and other premises and places hitherto understood as offering right of access to citizens without recourse to court Applications or warrants of any kind;

To order citizens that, in purchasing items in shops or similar trading premises, they must purchase only items conforming to specific criteria to be decided on the spot by Garda officers or other State actors, including but not necessarily confined to the requirement that these items be ‘essential’ for some purpose or intention to be decided on the spot by such Garda officer or State actor;

To permit members of An Garda Siochána to search without warrant any baggage, luggage or belongings which may be in the possession of a citizen in a public place;

To compel citizens in public places to refrain from sitting down, resting, lying on the ground, reading books, periodicals or newspapers, engaging in ‘non-essential’ conversations, under penalty of arrest and punishment by means of a fine or term of imprisonment;

To order citizens that, when entertaining friends, family members or other persons in their own homes, they must confine the attendance to a number of individuals to be dictated by Government order and must abide by rules of ‘social distancing’ by remaining a specified minimum distance apart from others persons at all times;

To prohibit the attendance at funerals of more than a specific number of persons, these to be subjected to checks by members of An Garda Siochána to ascertain and confirm that they are bona fide members of the family of the deceased.

The question then arises: What, then, does the Constitution of Ireland forbid, protect, prevent or restrict? If such previously understood fundamental rights and freedoms of Irish citizens as had been suspended in the Covid crisis could be so suspended without recourse to the sole provision in the Constitution allowing for the declaration of a State of Emergency — this for the claimed but not necessarily demonstrable purpose of maintaining public health, safety and order in rare and particular circumstances — what therefore remained of the ordinary meanings the text of that Constitution appears to state, insinuate or imply? What was the difference between this Constitution and no constitution? What was the purpose of the document, the courts enjoined to protect it, the oath taken by the President to defend it? What was the purpose of An Garda Siochána, now that it was clear that its role was no longer to uphold the ostensible meanings long assumed to be contained in the text of the Constitution? Was it now merely the unregulated security detail of politicians and other State actors, asylum seekers and refugees, abortion clinics, and public protestors of a particular ideological bent ? And, what, then, might henceforth prevent or restrict any group or individual seeking and positioned to curtail even further the rights and freedoms of citizens, on achieving governmental office by means which may or may not adhere or be subject to the ostensible meanings of the Constitution, from locking up every citizen of Ireland in a gulag and throwing away the key?

This is the situation in Ireland now, as a result of many years of piecemeal interference and bowdlerisation of the Irish Constitution, especially its (informally termed) ‘Bill of Rights’ section comprising Articles 40 to 44, but in particular with reference to the influence and bracing qualities provided by the influence of natural law. That constitution, and most of our laws, are rooted in natural law and English common law concepts of freedom. We are free people under God unless, for exceptional and proportionate reasons, our government is compelled to curtail those freedoms in the interests of the common good — itself a far more complex concept than modern politicians seek to suggest (another story). We do not receive our liberties from government, but from God (Nature, the Universe, et cetera), so such interventions are bound by an ethic of minimalist proportionalism. We, the People, grant the government any powers it may have. The People have the right to do anything — within the precepts of the natural law; the government has the right to do nothing except that which the People expressly permit. The idea, therefore, of the People being imprisoned in their own homes on the basis of a crisis — that, even as it began, had also already begun to reveal itself as grossly exaggerated by spurious and discredited projection models — was, on its face, deeply repugnant to the sovereign status of the Irish people as human persons. This outrageous situation was rendered possible by a history, going back some 25 years, of sustained judicial and political onslaughts on the concepts and credibility of the natural law.

I have repeatedly drawn attention to the fact that the Preamble of the 1937 Irish Constitution begins: ‘In the Name of the Most Holy Trinity, from Whom is all authority and to Whom, as our final end, all actions both of men and States must be referred. . . ’

It is nowadays not immediately obvious that this opening passage has also a secular interpretation, perhaps best demonstrated by reference to C.S. Lewis’s observation that when God is abolished by man, He is not replaced by all men but by a few men imposing their will on the rest.

Thus, even for non-Christians, unbelievers, secularists, atheists — whose worldview does not allow for the concept of transcendent authority — it is vital that they come to see the formulation at the heart of that Preamble — replicated in various forms in virtually every constitution of the Free World — not purely as a Christian invocation, but as a mechanism that achieves something as essential to their own protection as it is to the protection of the rights of Christians. The point is that the ‘mechanism’ provided by the Holy Trinity does something that cannot be achieved otherwise: it places the fundamental rights of men out of the reach of men, of usurpers, of would-be tyrants. Man has long understood that it is, for obvious reasons, essential that laws fundamental to human functioning and happiness be referred elsewhere — upwards, sideways, outside — though preferably not downwards. Certain rights are so fundamental and non-negotiable that they cannot be left to the mercies of human caprice or consensus — including, especially, certain personal rights, on which depend the security and freedoms of the individual; family rights, protecting the unity and cohesion of the most fundamental grouping in society; and collective rights, regulating the health and stability of the nation. Such rights were at one time universally understood to emanate from natural law, variously characterised as deriving from divine authority, or derived from the logic of human engagement with reality. By acknowledging God as the source of these rights, I have argued, the Irish Constitution removes them from the gifting or withdrawal of governments, courts, and even electorates, so that they cannot be interfered with by human agency — the people ‘give themselves’ a constitution, consisting of strictures and procedures, as well as various ‘acknowledgements’ of what the natural law permits, but do not themselves generate these precepts or have the right to confiscate their benefits from themselves. The Holy Trinity is here more and less than a prayer: it is a mnemonic as to the actual conditions pertaining to reality, the structure of that reality and of man's correct place within it.

It is in this light that we must read the language of the Constitution — and its insistence on repeating certain words that are as hard as anthracite — as something other than ornamentation. John Finnis insists that, contrary to the emerging tide of opinion precipitated by self-interested politicians, judges, journalists and others, there remains a viable concept of absolute human rights, because it is always unreasonable to choose directly against any basic value, whether in oneself or in one’s fellow human beings:

‘And the basic values,’ he continues, ‘are not mere abstractions; they are aspects of the real well-being of flesh-and-blood individuals. Correlative to the exceptionless duties entailed by this requirement are therefore, exceptionless or absolute human claim-rights — most obviously, the right not to have one’s life taken directly as a means to any further end; but also the right not to be positively lied to in any situation (e.g, teaching, preaching, research publication, news broadcasting) in which factual communication (as distinct from fiction, jest, or poetry) is reasonably expected; the related right not to be condemned on knowingly false charges; the right not to be deprived, or required to deprive oneself, of one's procreative capacity; and the right to be taken into respectful consideration in any assessment of what the common good requires.’

The desire of establishments to dispose of these absolute rights is the true terrain of the recent Irish battles to prevent the piecemeal erosion of the fundamental and personal rights sections of the Irish Constitution. In the referendums of 2012 and 2015, a few of us divined a plundering of the fundamental rights of families in a manner that was actually illegal, unconstitutional, and profoundly dangerous. In effect, the Irish government performed two sleights-of-hand, both times convincing the public that it had a right to vote on matters that were actually beyond the remit of Government and People. The targeted articles in 2015 and 2018 had made clear that the rights set out in their texts were not extended or generated by the State, but were ‘antecedent’ and simply ‘recognised’ within the constitutional text. In 2020, as though by way of coup de grâce, virtually all the rights inherent in or implied by Articles 40 to 44 were ostensibly suspended, though in reality confiscated. By unilaterally granting themselves the entitlement to suspend them, the relevant authorities were already acting ultra vires the Constitution, and having done so could not be trusted to restore the natural order or decline to disturb it again.

Allowing men dominion over the rights of men has long been recognised as the first step on the road to despotism, and the sole effective mechanism that man has discovered to avoid this is to acknowledge the source of these rights as residing in the hands of God, i.e. as defined in the Irish Constitution as the Holy Trinity. If this is a ‘sectarian’ presumption, then it seems an essential and non-supplantable one. I have several times issued this challenge to secular-atheists: If you can outline an equal or better mechanism for achieving the same thing, I will support you all the way in seeking to alter the Irish Constitution for a ‘modern secular republic’. We shall return to this question in a subsequent article.

In the second part of this series, I intend to outline, by way of an example of the stealthy assault on natural law, the history alluded to above, whereby the natural law elements of the Constitution of Ireland — the guarantees of the fundamental rights and freedoms of the people — were usurped by a pincer movement of politicians and judges, with the clear objective of softening up Irish society for the authoritarianism we have recently observed. In the third and final part, we shall look at the chances of rescuing Western civilisation from the effects of this overreaching, and restoring natural law to the centre of our affairs.