Ireland: Birthplace of the Totalitarian, Part II

In a certain sense, it's possible to see here a stream of continuity — not of events, direct meanings or cultural logic, but in the form of an inversion, an involution, occurring by way of a reaction.

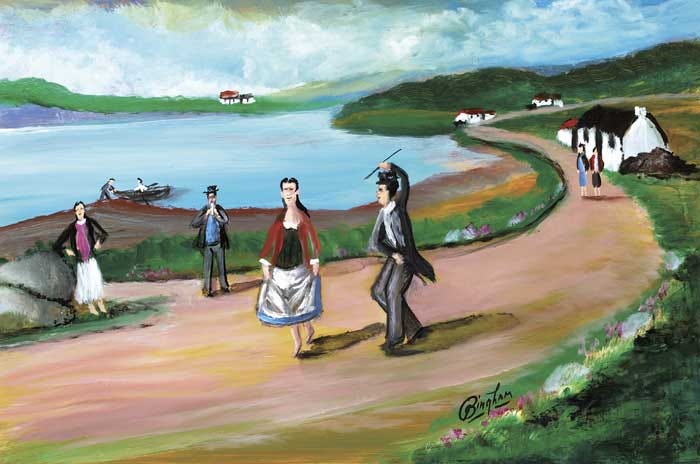

‘Dancing at the Crossroads’, by James Bingham, (1925-2009)

The Danceless Death of Ireland

[This article may be too long for the Substack newsletter format. If you’re reading it as an email and it tails off unexpectedly, please click on the headline at the top of the page to be taken to the full post at Substack.]

The symptoms of what became Ireland’s most debilitating post-Independence pathology were slow to be spotted by sociologists, psychologists and the like, it being assumed that the roots of every ‘national’ problem lay in economics. Even (perhaps especially) domestically, as with many matters relating to the subjugation of the Irish people, the issue was ignored and, if mentioned, denied, the conventional willy-nilly wisdom being that the Irish were a fecund population, in which large families were commonplace. It was via the Irish diaspora in North America that the issue first came to significant public notice, not least because it was becoming clear that the ex-pat Irish population in America was itself labouring under some unusual symptoms of late marriage and relative childlessness compared to other ethnicities in the New World.

The first signs had been noted in Canada, even before the declaration of Irish independence. In 1917, when the Archbishop of Toronto, Neil McNeil, brought the matter to the attention of scholars in Notre Dame and Fordham Universities — both in the United States. This created a flurry of articles in American magazines, which drew attention to the mysterious failure of the Irish community to reproduce itself in anything resembling the numbers manifested by other ex-pat communities. In the early 1920s, while Ireland went to war with itself, these academics were publishing articles in America magazine with titles like ‘Are Irish Catholics Dying Out in This Country?’, ‘Catholic Bachelors and Old Maids’ and ‘The Disappearing Irish in America’.

One of the academics centrally responsible for this opening-up of the issue was Dr James J. Walsh of Fordham University, who also noted that the tendency towards late marriage or spinsterhood/bachelorhood was especially noticeable in families which had produced priests or nuns. Celibacy, he observed, seemed to be accepted as the ideal, even by those remaining in the secular world. ‘I am sorry to say that the more priests and religious there are in the family, the less tendency does there seem to be for other members of the family to get married.’

This factor comes in for intense study in various articles in the 1954 volume of essays, The Vanishing Irish, but the analysis there invariably fell short of a definitive prognosis as to the reasons for and functioning of this strange symptom. It is loosely speculated in the book that an excessive reverence for the celibate state might be causing some kind of resistance to engagement with the opposite sex, or to the contemplation of marriage and procreation as proper pursuits for Catholics. Several of the essays touch on this topic and a couple delve into it with some gusto, but what emerges in the end, being invariably couched in whimsical theory and quasi-comical anecdote, falls short of a conclusive analysis. Undoubtedly, deference to the Catholic Church and its power prevented any definitive diagnosis being arrived at.

There are, however, some interesting contributions, with subtly different emphases, which almost invariably cast the spotlight into the prevailing cultures of Ireland and Irish-America, rather than considering the likely root causes and connections to history and its undertows. The Irish playwright, Paul Vincent Carroll, for example, speculates that the cause may lie with the ‘mysticism’ of the Irish male:

He knows, even when he is making a fool or an exhibition of himself, that all life is a gloriously disguised fake. He is only too pathetically aware that all these foolish things will pass. . . . To be precise, materialism has never captured the inner being of the Irishman, as it has captured the entire being of, say, the American. . . . [G]ive an Irishman the king’s robes and jewels, and at the mystical fall of evening the illogical fellow will go hungering after some undefined something that is positively unattainable. He knows he is the lost child of some celestial hall of high splendours and that there is no real satisfaction for him in the tinselries of earth. Somewhere deep underneath his humbugging and his jollifications, there is a restless yearning that has no name.

For this reason, Carroll claims, women hold out no mystery for Irishmen, as they do to the males of other races. Women, being materialists of nature and necessity, will seek, in pursuing the affections of an Irishman, to ‘capture him from his dreaming’ and ‘lofty preoccupations’, and bind him to the marriage bed ‘which he dislikes, and the grinding stones which is the nightmare of his private raptures.’ This does not mean, he stresses, that the Irishman is a celibate — far from it; but, if he marries, it will be ‘when the blood runs cooler and he requires the comfort of a nurse and housekeeper.’

A (to some extent) related thesis is developed by the Irish journalist, Mary Francis Keating, sister of the painter, Seán Keating, who says simply that ‘the Irishman hates marriage’. He will dally with women for a time, but does not especially like them. ‘He is not a good husband or father, and the blame for the fact that the Irish are a vanishing race must be laid squarely and solely on his shoulders,’ though she hastens to urge that we not ‘pile all the blame . . . upon the shoulders of those few Irish who are extant today’. This rather stereotypical feminist appraisal of Irish manhood is somewhat redeemed by the analysis which follows concerning the cultural effects of male detachment upon women:

The Irishwoman has had to become the ‘dominant’ female, a role which suits her ill and makes her quite frequently dislike herself heartily. It earns for her, too, the dislike of the man.

In marriage, she alleges, the Irish woman must of necessity become a bully, who compensates herself for the deficit of husbandly love by imposing a stranglehold on the children, refusing to permit them to grow up, ‘lest they fly away the first chance they get.’ This, she says, is what deters young men from seeking wives — or, as she puts it, ‘getting emotionally involved with other people’: they are trapped in the adoration of their mothers and have neither motivation nor opportunity to escape.

Margaret Culkin Banning writes of the ‘ferocious chastity’ of certain categories of Irishwomen and the ‘instinctive modesty’ of Irishmen.

Catholic girls of Irish descent, even when the Irish blood is considerably diluted, have the same instinct of modesty. Before them always, and from childhood, is the ideal of the Virgin Mary, and so both their training and their temperaments work together to curb passions before marriage or without it. It is also against the instinct of these girls to seek men. They may have the ‘come hther' in their eyes, but today other girls use more direct methods of attraction, which are both forbidden and repugnant to an Irish-American Catholic girl. It is not that the Irish do not like sex, but they have always disciplined sex. They have found and they have seen, in their admired priests and nuns, that life can be lived without it.

The writer, Bryan McMahon, wanders closer to the core of the issue when he speaks of the arcane Irish Catholic trope of ‘company keeping’, in other places and cultures known as ‘romance’.

Looking back twenty or thirty years, it would appear to me now as if the whole artillery of our Irish church had been brought to bear on that mysterious subversive force — the ‘company keepers.’ If from any pulpit there had been slight reference to company keeping of a laudable nature — as of course there must have been — my adolescent mind did not adequately register it. Never can I recall there being placed before me the possibility of connubial happiness, the essential incompleteness of single man, or the essential incompleteness of single woman.

Twenty or thirty years before, he recalls, ‘open-air dancing at the crossroads was in full swing’, but this was brought to an end by clerical killjoys.

I do not say that these dances were entirely without blemish, but they were as near to being so as blemished human nature will ever allow. One does not raze a house to the ground if a window is broken; yet this system of dancing was smashed largely as a result of a campaign by the clergy. Wooden roadside platforms were set on fire by curates: surer still, the priests drove their motorcars backward and forward over the timber platforms; concertinas were sent flying înto hill streams, and those who played music at dances were branded as outcasts.

How clearly I recall a band of laughing boys and girls on a fine Sunday afternoon dancing ‘sets’ on the floor of a ball alley by the sea. Suddenly the cry of 'The priest!’ is heard. The dancers scatter in terror; the lame fiddler bobs brokenly after the others. Even at that time to my young mind, the incident didn't make sense. I thought it would be more fitting if the priest sat on a chair at the edge of the platform and smiled at the dancers, the while he paired them off in his shrewd mind.

I recall with sorrow now, but with what then seemed to me to be the refinement of humor, the spectacle of a fat man jammed in the end window of a boathouse whence an afternoon dance had scattered in alarm: there fixed forever in my memory is that fat man poised for the blow from the sacerdotal umbrella. I once saw a parish priest at dusk wearing a postman's cap so as to steal up on company keepers

It seems true to say that this emphasis on the sins of the flesh, thundered out at mission after mission, has rendered the Irish people among the most chaste in the world. But again as the result of the fatal Celtic trait of overcompensation, this chastity has projected itself beyond what is right and in many instances has ended by warping virtue into vice. Many a young Irish bride has suffered mental agonies in being unable to make the mental adjustments necessitated by the marriage state.

And curiously enough, it may be noted here, very many factors, earthen though they may be, leading toward marriage among Irish countryfolk, would appear to me to be of pagan origin. Superficial consideration of this fact presents the unthinking with the wrong idea that the Church has no reply whatsoever to the question of the beautiful but complex relations obtaining between man and woman.

Seán Ó Faoláin, one of the most celebrated Irish novelists and essayists of the mid-twentieth century, in a chapter titled ‘Love Among the Irish’, obsessed that the old canard that Ireland’s misfortune had been entirely down to foreign misrule had been rebuked by the events of the early years of Irish independence. This has since become a rather simplistic strawman argument of revisionists, but Seán Ó Faoláin elaborates upon it in a manner as to render it more compact and subtle. (Ó Faoláin it was, by the way, who inspired the publication of The Vanishing Irish, having written an essay on the Irish demographic crisis for Life magazine. He it was, too, who introduced the most dramatic and accuract descriptions of the crisis: ‘racial haemophilia’ and ‘racial decay’.)

Having excluded conventional arguments about economics and housing, he goes on to dismiss poverty as the primary reason for the collapsing demographics of the Irish nation at home and abroad. On the contrary he argues, it was the glimpsing of prosperity that had placed an impediment between the Irish and taking the plunge:

What is creating the psychological block here is something far nearer to the opposite of poverty. All our young people are developing a proper concept of what constitutes decent living conditions, and until they get them, they are on strike against marriage. We are rearing generations in Ireland that have ten times more pride and ambition than their parents ever had, and good luck to them for it. As one young woman put it to me in two sentences: ‘I saw what my mother went through. Not for me, thank you!’

Then he nudges close to the nub of the issue, citing a young male correspondent:

We Irishmen have been conditioned into a state of sexual frigidity and repression because for generations we have clothed the sublimity of love in shrouds of taboo, false prudery and an attitude of Victorian Puritanisn that hạs given to the act of sexual union the blasphemous nature of something offensive.

But then Ó Faoláin somewhat pulls his punch. If, he editorialses, this attitude has been fostered by the Catholic Church, (‘and I am afraid it has been’), it has not been fostered ‘consciously and deliberately.’

How could it be? It is the doctrine of the Catholic Church that to seek satisfaction of bodily desire in sexual union, that is, in marriage, is one of the most virtuous functions of mankind, a holy act in which God and man must take constant joy and delight. It has been fostered, most unhappily, because the young people will not marry young and the clergy fear that the result must be a relaxation of sexual morality. The stage is set for conflict and an impasse. The Church thunders against the dangers of sex. The young men, obedient up to the point of marriage, at which they balk, are inevitably conditioned into a frustrated terror of woman.

This rings a bell or two, though it is far from clear that he is correct about this not being done ‘consciously and deliberately’ — as we shall see.

But then Ó Faoláin goes on somewhat to contradict himself:

I am an Irishman and a Catholic. I live in Ireland. I am bringing up my children in Ireland as Catholics. I fully acknowledge the right of the Catholic clergy in Ireland to adopt any attitude they think fit toward the problems of young love. I am simply objecting that the position I see adopted by the state and by some of the clergy in Ireland is shortsighted, inhuman, unwise, and may be fatal to both.

Since my boyhood I have heard my elders fulminatíng about keeping company, night courting, dancing at the crossroads, V necks, silk stockings, late dances, drinking at dances, mixed bathing, advertisements for feminine underwear, jitterbugging, girls who take part in immodest sports (such as jumping or hurdling), English and American books and magazines, short frocks, Bikinis, cycling shorts, and even waltzing, which I have heard elegantly described as ‘belly-to-belly dancing.’ Perhaps the most extreme example of this kind of thing was to hear woman described from a pulpit to a mixed congregation as the ‘unclean vessel.’

Enough. What we need, surely, is the lifting of an unclean cloud. For a picture of a saner attitude to woman go into any southern city of Europe. There the God-given beauty of woman is almost adored. Courtship is frank and fair. The youths discuss the charms of their girls openly and with enthusiasm. Their songs are of love; their thoughts are of love; their blood is at natural blood heat. They marry young. While the population of Ireland is dwindling, the population of Italy, a much poorer country, is soaring.

Unless this changes, he says, both Ireland and the Church will continue to lose out:

If some such revolution does not take place, it can mean only that that impalpable thing we know as the Irish nature is shrivelling and hardening into selfishness, is growing less and less attractive in its smug blindness to the unhappiness of this generation and the threat to the generations of the future. In that sense the Irish whom the world has known, and admired, may indeed vanish from the earth; and I am still proud enough of my race to think that their disappearance would be the world’s loss.

What we observe, then, looking at the problem as a decline stretching not over a century but over a virtually continuous period of 180 years, is a nation deprived of the opportunity to love itself, being interfered with in more or less equal dimensions from both Rome and London, continuously seeking its salvation externally and finding no fulfilment anywhere — more than a little like John Joe, in Tom Murphy’s play A Crucial Week in the Life of Grocer’s Assistant, who was ‘a half-man here and a half-man there, and how I can I ever hope to be anything?’

Some years after the publication of The Vanishing Irish, the German writer, Heinrich Böll, who was a frequent visitor to, and resident in, Ireland in the 1950s and 1960s, when he owned a cottage in Dugort, Achill Island, wrote in his Irish Journal about the dismaying changes he was noticing then, despite the onset of what he termed ‘prosperity’. Since the years 1954/55, he wrote in 1967, Ireland had 'caught up with two centuries and leaped over another five. We live in a country in which, for a very long time, shrinking family sizes have been touted as something akin to a sign of progress, as indeed have escalating crime statistics. It is at once chilling and educative to observe how a society can be persuaded that its destruction is some kind of victory.’

Böll actually identified the onset of another demographic apocalypse, dating from — approximately — the year of my own birth, and had an unambiguous view of its cause. When he first came to Ireland, at the start of the 1950s, he had optimistically predicted that the country might be able — just about — to maintain her population through the coming years: ‘Of the eighty children at Mass on Sundays,’ he wrote, ‘only forty-five will still be living here in forty years; but these forty-five will have so many children that eighty children will again be kneeling in church.’ By the 1990s, arising mainly from emigration, the 45 adults that Böll expected to remain at home in Achill was more likely to be 25 or 30, and the 80 children he hoped to see kneeling in church was likely to be half that, at best. By the late 1960s, he was attributing the problem to a specific factor (Böll was an unorthodox but staunch Catholic):

. . . a certain something has now made its way to Ireland, that ominous something known as The Pill — and this something absolutely paralyzes me: the prospect that fewer children might be born in Ireland fills me with dismay.

This may have been an over-simplification of a problem that, even today, remains a mystery in its depths, as Ireland’s indigenous population continues its collapse, now into what may be a terminal pattern.

However, by the 1970s, seemingly at once contradicting and affirming Böll’s prognostications — as if his and other warnings had been heeded — the national fertility rate had climbed to nearly 4, indicating that ‘we’ already knew that these drifts need neither be definitive nor necessarily terminal, and that there is no need for external assistance in righting them. The ‘rational’ explanation for this shift was what is remembered as ‘the Lemass era’, which briefly staunched the outflow of Irish people and enabled the emergence in the 1970s of a uniquely Irish ‘baby boom’, which briefly changed the face and mood of Ireland into a much more positive and forward-looking nation, a disposition that appeared to sustain until approximately the early years of the present century.

Today, while our pathetic political class boasts that Ireland is now ‘the wealthiest country in the world’, the Irish population is again collapsing and being replaced by outsiders who barely know — or care — where they are. The zeal for abortion must surely be listed as one of the key manifestations of the modern withering disease (10,000 baby-killings per year since legalisation on January 1st, 2019), as must the silence that has met the inundation of Ireland over the past two decades with what are insultingly termed ‘the New Irish’ — mostly fake refugees, fraudulent asylum seekers and others who have come here as part of a wave of displacement now occurring on a global basis, but accompanied here by a particular undertone of utterly baseless historical retribution being directed by Irish politicians against their own people. Without public consultation — even in the most affected communities — the political class, under instructions from elsewhere, threw open the gates and invited the world in to steal the little peace the Irish people had generated for themselves and their descendants after a millennium of trial and heartbreak.

Clearly, the circumstances of today are utterly different to those which obtained 70 years ago, at the time of the publication of The Vanishing Irish, though not in a good way. At that time, for all the difficulties being experienced by Irish people, it would have horrified every sentient Irish person to hear it proposed that the solution to Ireland’s difficulties might be to import hordes of semi-feral youths from the African continent and other Third World locations. Such an option would not have been dreamt of, not even satirically by some aspiring Jonathan Swift. Yet, this is at least the cover-story being proffered: that Ireland ‘needs’ these immigrants for her economy. But, of course, what is being spoken of is not an Irish economy at all, but a transnational, cuckoo-in-the-nest economy, operating on Irish soil for the purposes of tax evasion, an economy conferring only moderate run-off benefit on the indigenous population in a fashion that is ambiguous in multiple ways, and may soon prove terminal in one staggering aspect: that it is resulting in the stealth transfer of Irish assets to the ownership of outsiders and traitors.

The real puzzle, as in 1954, is the silence greeting these events within Ireland herself. A tiny minority continues to resist the re-plantation, and are demonised for their trouble by mendacious, criminal politicians, and purchased journalists. Beyond that, the main ‘herd’ of what was once the proud Irish people has settled into a sullen, semi-terrified silence. They are silent because the sole alternative is to invite the appellation of ‘racist!’ and that scarifies them, it seems, more than telling their children that they will no longer have a country to live in.

If the circumstances of Ireland 1954 were — as characterised in The Vanishing Irish — a ‘mystery’, then the general demeanour of the Irish in 2025 might be termed a dark enigma.

But there may be clues. In a certain sense, it is possible to see here a stream of continuity — not of events, direct meanings or cultural logic, but in the form of an inversion, an involution, occurring by way of a reaction to the circumstances which created the problems analysed by those doughty writers, academics and intellectuals seventy-one years ago.

Back then, as in some charity proposed in Part I of this short series, what was really in train was an unseen collateral catastrophe arising from a broadly well-intentioned initiative to rescue the Irish population from patterns of behaviour which, in the material circumstances prevailing, might have brought further catastrophe down upon their heads. But in the end this went too far and, going too far, resulted in a warping of the Irish personality in one of the most fundamental ways imaginable: the very means whereby the species is constructed to replicate itself.

We can say that, for a period within the lifetimes of contemporary elders — starting in the mid- to late-1960s, and continuing, with some turbulence until, say (depending on the focus or depth of your analysis) 2008 or 2019 — there appeared to settle upon the Irish nation a semblance of normality, and this normalisation of the bizarre may lie deep as a root cause of our present blunder towards obliteration.

In the first place, as I have demonstrated, the true nature of the disease was incompletely diagnosed. It was not primarily an economic, social or cultural problem, but one of mass psychology. It was that the Irish people, deep within the folds of their culture, had begun to be conditioned to revere womanhood in a fashion and to an extent that was counter-productive in literal terms, and concomitantly to regard men with suspicion. This pathology, for such it was, caused both males and females to develop, as though from the cradle, a repugnance of the physical acts associated with procreation, thereby attaching to the attraction that exists naturally between males and females a form of neurosis which caused that which ought naturally draw them together to be attacked as though by a form of cultural virus which, once contracted, thereafter served to repel. This non-culture, enforced by a hyper-zealous clergy imagining itself to be ‘saving souls’, and combined with the practical circumstances created by necessity or lack of options, imprisoned multiple generations of Irish men and women in a dance of mutual avoidance. At the heart of this pathology was the unspoken notion of the woman as Virgin Ideal, as though every woman were herself an immaculate conception, and therefore ought properly to remain ‘pure’. The opposite epithets of ‘immaculate’ are ‘dirty’, ‘grubby’, ‘bad’ and ‘damaged’, and to avoid them, men and women had to avoid one another, which the culture constructed around them made it easy to do.

One contributor to The Vanishing Irish recalled a recently-married neighbour who told her about her mother-in-law coming to visit shortly after the wedding. The guest’s quarters for the night were to be the newly-decorated nursery, ‘papered with woolly lambs and ABC blocks’, and the daughter-in-law enthused to her: ’Jack and I can hardly wait until we have it filled.’

The response was : ‘You dirty thing!’. It was not intended jocosely.

Is it possible that this attitude may continue to manifest in the Irish of 2025? Yes, though only in involuted, ingrown form. As a result of the moral inversion that has gripped Ireland as a consequence of its acquiring a subliminal half-understanding of what was done to it, the energies of repression and self-denial have been flipped into their opposites. Where once there was prudery and moralism, now there is flaunting and abandon. Where once the Church’s word was writ, now it is abominated and resisted to the limit. Hence, in the ‘modern’ era, Ireland, corporately and culturally, seeks to present itself as having sloughed off its Catholic past, and it does this by embracing any and every tendency upon which the Church has historically frowned, as though life itself depended on it. Thus, what is sensed and interpreted as ‘freedom’ is actually a neurotic casting off of an earlier repugnance, arising from a deep embodied sense of being deprived, even perverted, by a mechanism that almost nobody ever speaks of in its precise detail. This may be what has created the sudden, lurching inversion of morality that has occurred in Ireland in recent years, perhaps best illustrated by the hordes of young people in the yard of Dublin Castle, in May 2018, cheering and toasting the result of an abortion referendum in which the green light was given to the wholesale slaughter of the innocent unborn.

The problem is that these tendencies and devices, without exception, combine to create as though self-constructing mechanisms which have the same effect as the puritanism of old: they arrest the possibility of new life entering the world. The more obvious examples of these modern equivalents of the prudery and prohibition of the past are abortion and contraception and the virtually year-round public celebration of homosexuality, which Ireland has embraced as though its life depended on them, whereas it is clear that these, too, promise nothing but death. And there are, as in the past, subtler modes and codes whereby the same outcome of sexual segregation is achieved: culturally and economically-transmitted mechanisms that make relations and relationships between the sexes increasingly difficult and even dangerous. One such is the impossibility of a couple, even one with two decent incomes, achieving the means to acquire their own home. At the other end of the spectrum are the male-demonising cultural conditions imported from abroad in the form of concepts such as ‘toxic masculinity’, ‘date rape’ and ‘#MeToo’, which serve to drive immobilising wedges between young men and young women to the point of rendering ‘heteronormative’ relationships increasingly improbable.

The upshot of all this is that ‘modern’, ‘progressive’, ‘liberal’ Ireland — even before we get to the issue of mass corrective inward migration — has become a very cold place for romance. To see a young couple — male/female, at least — holding hands in public in ‘modern’ Ireland is a rare thing.

Unsurprisingly, then, Ireland’s fertility rate can be observed to have declined almost continuously since 1850, with a substantial period of relief in the second half of the twentieth century, which has now evaporated in a manner suggestive of a catching-up. In 1940 fertility was 2.6 (children per adult female); in 1950, 3.5; in 1940, 4.0. After another dive in the early 1950s, the situation started to improve beginning 1955 until 1965 (reaching 4.0 again in that year), before resuming its downward trajectory. Since then, with relatively intermittent minor corrections, it has been in continuous decline — to a current level of 1.5, albeit that this is substantially buttressed by births among foreign residents, including an unknown number who are designated as ‘Irish’, who are nothing of the kind. A marked peculiarity of the figures is that the graph suggests that the continuous pattern tracked from 1940 to 2020, is approximately now at the level it would have reached had the upward surge of the 1940-1970 period not occurred, as if the actually underlying downwards trajectory of the Irish population has continued in late years in the same downward line as it followed between 1850 and 1940, picking up around 1995 at the point it would have reached had the Lemass boom never happened, and continuing to the 2020s on the same path. This clear picture is now being ‘corrupted’ by coercive mass plantation, emanating and largely orchestrated from outside, and fudged by dishonest reporting of mendacious statistics by purchased ‘journalists’.

Statistically speaking, even demographically speaking, it is as if the same mass hypnosis remains in place as at the height of the devotional revolution in, say, 1900 — that it has sustained right through the years of Ireland’s Independence and apparent normalcy as a ‘modern’ nation. But, it will be protested, the conditions of the late 1800s have long since abated, and the Catholic Church is in retreat, having been as though ‘democratically’ rejected by a growing majority of its people from the early 1990s onwards. Yes, but this does not guarantee that the mass hypnosis does not remain in place. For all the outward manifestation of a radical alteration of the beliefs and behaviours of modern Ireland, the underlying trend is undeniable, albeit that, now, it acquires new forms, as though driven by new logics. In reality, these are not new ways of thinking, so much as involuted variations on old pathologies. Under the attrition of the national moral inversion, virtually every value of the past has been flipped into its antithesis. In a certain light, it is possible to see this as a neurotic rejection of Catholicism, and everything to do with it — with the possible sole exception of the person of Jesus Christ. Thus, sexual prohibition becomes sexual license; prudery becomes exhibitionism; ’heteronormativity’ belies ‘whatever you’re having yourself’, and so on.

And this culture is just as hard on procreation as even the best efforts of the foot soldiers of Cardinal Cullen, as though the subliminal message survives, in spite of ‘modernisation’ ‘industrialisation’, ‘education’, ‘progress’, ‘growth’, ‘prosperity’, and ‘enlightenment’. Somewhere deep in the Irish psyche, the same message seems to persist: do not reproduce thyself — a message planted by colonialism but fuelled by a warped religiosity to effect an almost uncanny suppression of one of the most fundamental of human urges.

An obvious question is: how might these conditions transmit themselves through time, and across a line of apparent rupture, whereupon the conditions turned into something that might be described, if only ideologically, as their ‘opposites’? One convector, undoubtedly, would be guilt, both of the imposed colonial kind, whereby the native is conditioned to hate himself and his culture, and of the religious kind whereby people are bullied into exercising supposed ‘virtues’ — sexual abstinence then, something called ‘compassion’ now — regardless of their own instincts and desires, or the risk such responses may involve for themselves. Such a perversion has clearly now recurred, in part again at the hands of the Catholic Church in the current situation of Ireland, as a consequence of the preaching of globalist Catholic clerics whereby it is insisted that Irish people have some kind of moral obligation to take in unlimited numbers of ‘refugees’ and ‘asylum seekers’, regardless of the consequences for their own survival or their children’s birthright of a homeland to belong to.

Apart from all the other problems and mendacities associated with this recent plague of bullying, it is manifestly contrary to the Church's own teaching, as laid down by St Thomas Aquinas, all of 750 years ago.

It is clear to any sentient mind that Aquinas’s analysis is both reasonable and prudent, and moreover accords with the common sense outlook of any balanced reasonable person. But it is not what the Catholic Church has been saying for the past dozen years of the Bergoglio pontificate, and may by many accounts be set to continue under his successor — an infidelity of mission that has perpetrated enormous mischief within Western societies, and not just the predominantly Catholic ones.

Another possible convector of the conditions of nineteenth century Ireland is undoubtedly the emasculation of Irish males as a result of the circumstances created by the devotional revolution, and its modern successor, the feminist war against men. In the first dispensation, the mother became in effect the head of the family, under guidance and instruction from the priest, and Ireland became a matriarchy disguised as a patriarchy. The father was marginalised and ignored for all matters except those relating to business, which in most instances meant the running of the family farm. In many homes, where the father had died and one of the children had inherited the farm and got married, the mother/grandmother remained the de facto head of the household, exercising enormous power over the emerging generation, if any.

Although, in ‘modern’ Ireland, the priest is out of the picture, and women have now moved in large numbers into the workforce, the power of women over matters of family, household, education and other key areas remains intact, with the father featuring chiefly or solely in economic contexts, and suffering almost total banishment from the lives his children in the event of a separation or divorce. The pathologies of old find new forms at the level of collective identity, but the outcomes remain the same.

It is a matter rarely remarked upon directly, but constantly presents as an all but axiomatic credo, that Ireland is actually female, a woman: Róisín Dubh; Dark Rosaleen; Godess Ériu/Érin; Cathleen Ni Houlihan. Saint Patrick is the Patron Saint of Ireland, but Saint Brigid of Kildare is his spiritual mate in the iconography of Irish mythology. The downside of this is that the earlier veneration of woman as virginal ideal has metamorphosed from a spiritual to an ideological condition and, infected by the moral inversion, has driven Irish culture, albeit in a different direction, to a place and condition demographically indistinguishable from the time of the devotional revolution. The numbers of the native population are in nosedive mode, and this is deemed to be ‘progressive’.

Meanwhile, Ireland herself has become something untouchable, something desired but in a manner that is best as an issue of shame, or guilt. Gone is the patriotism that characterised my parents’s generation, from the 1920s onwards, and inherited by those born up to about the mid-1960s, but afterwards coming under attack from ‘republican’ murderers and revisionist ‘historians’. In the decades after 1970s, the traces of a profound love for Ireland were to be seen almost solely in the rows of tricolours of the terraces where stood the supporters of the Irish team playing what used to be called a ‘foreign game’. More recently, the flag is lamented and all but disowned on account of having fallen into the hands of the ‘far right’. Éiriú, as a consequence, is unloved and uncherished. The Irish no longer have a language in which to express their love of country. And so our Dark Rosaleen becomes an old crone from a fairy story, who wastes away on her deathbed while the streets are alive with the harsh tones of foreign accents and ‘proud’ nonces peddling every manner of perversion.

One of the most disgusting tropes to be heard emanating from the vested interests in this neo-plantation Ireland is the idea that this national decline is somehow an organic (and therefore unavoidable) phenomenon and that, accordingly, radical surgery is required to save Ireland from the consequences of an organic, chosen lack of fecundity of its population. In actual fact, it is quite clear that these conditions have been engineered for a very long time, and continue to be so, albeit that the methodologies have changed from devotional revolution and the rhythm method to contraception, abortion and incessant manipulation of the economic model to simultaneously maximise the ostensible metrics like GDP and revenue surplus (all foreign owned and controlled) while preventing the emergence of an Irish economy capable of maintaining the indigenous population in reasonable comfort and decency. Ireland does not need immigrants to survive or prosper; what it needs is its own people being given a chance to live decent lives in their own country, and raise their children in conditions which they have a right to expect, having already paid for this all their lives. The idea that Ireland’s population needs replacing because of some congenital inability to grow itself is a profound insult added to the hurts imposed on the Irish people through history, both by outsiders and their own supposed leaders and representatives, and the unelected clergy which loiters at the margins, with judgement poised on a hair-trigger. In truth, the Irish have never been able to steady themselves enough to set down a clear philosophy or plan for their own survival, which has allowed outsiders and domestic mediocrities to decide their fate and future, and this, in large part, arising still from interference, alternately, from London, Brussels and, diminishingly, Rome.

Given the patterns of indigenous demographics, it is difficult to ascertain how the authorities-without-authority make the claim that the proportion of non-nationals currently living in Ireland is (depending on the instant source) between 20 per cent and 25 per cent. Less than thirty years ago, in 1997, the population of the Irish Republic was approximately 3.6 million, and in the meantime the birth rate has decreased by more than 20 per cent. In view of this, it is hard to understand how, with a total acknowledged population of more than 5.2 million today, the non-indigenous sector — allowing for the various inflows, outflows and sleights of hand in use to camouflage these figures — could be significantly less that two million, or approximately 40 per cent. This would certainly tally with the impression to be gleaned on virtually any urban Irish thoroughfare or streetscape.

It is impossible to imagine what men like John D. Sheridan, Seán O’Casey and Heinrich Böll would make of all this, though we must allow for the possibility that, like most of their modern equivalents, they too might well be rendered mute by the culture of menace and inducement now prevailing.

The conditions of ‘despair’ and ‘withering’ described by these great writers have now metastasised in our culture, albeit accompanied by an almost total absence of internal commentary — i.e. aside from that emanating from independent voices, officially termed ‘the far right’. The bought-and-paid-for institutional media refuses to lead any kind of discussion on the topic except by way of demonising those who raise it, but instead ensures that fake money is employed to remake our country to an entirely different design. We may for the moment shrink from contemplating what the ultimate outcome of this process will be like, but the facts of life will increasingly become as unavoidable as they may now seem unthinkable, as the swell of domestic outrage rises in proportion to the growing but belated consciousness of the hopelessness of our situation arising from the terminal condition of the Irish nation.

One of the most disgusting things being attempted by the purchased Irish political and media classes is the weaponising of historical Irish emigration as a tool to blackmail the present generations into handing over their country to strangers. ‘We travelled all over the world!’ they tell us, as though speaking of journeying anthropologists or tourists, rather than desperate skeletons, dragging their feet behind them in a race against death. It is beyond imagination to contemplate the rancid lies and cynical utterances of these paid quislings who are utterly shameless in their abuse of the memory of those starving hordes of human sacrifices who were driven out of Ireland by precisely the same longitudinal forces that have orchestrated the present invasion.

For 180 years, our people have had to flee their country because of the venality of the British Crown and the complicity of the domestic turncoats and traitors seeking to profit from the destruction and destitution of their country — then as now. Now we are receiving an education in aspects of our history that baffled us as children — like how Irish people could have conspired against their own, taking the shilling when the cost of it was measured in graves of all sizes, many of the watery kind.

Our people did not go abroad for adventure, any more than they went answering advertisements from foreign governments; nor did they go in search of social welfare, free houses and other benefits. Nor, for that matter, did they go to foreign lands and demand, accept and then belittle the generosity of the countries offering them refuge.

The story of the Irish in America is nothing like the stories now unfolding, of Somalians or Pakistanis or Indians in Ireland cockily telling the natives that they are there to replace them. Our people spoke English and assimilated into the melting pot that was the emerging America, embracing the culture they encountered with good grace and gratitude, whereas the 'New Irish' are invited — by NGOs financed in part out of the pockets of the indigenous population, in part with fake money generated for the purposes of civilisational destruction — to treat their hosts as racists and oppressors from the start. Our great-aunts and great-uncles were among those earliest settlers in the New World, and their passion to survive — as well as their willingness to commit everything they had to realise their dreams of a new and better life — bears no resemblance to what is being perpetrated in their homeland today.

America was, in a certain sense, largely unclaimed territory — as was Canada, so there is no comparison. Ireland has no rolling frontier; there is no project of expansion to be undertaken or completed.

The original Irish settlers in America were one of the foundational settler communities and became all but immediately their own ‘hosts’, and conveyed the nature of the frontiersman project to their relatives and neighbours back home, saying, ‘Come! Come! You are needed, there is work!’, not, ‘Come, there’s easy pickings, free houses and money!’ Those who survived the journey got no state assistance but went to join an Irish community-in-exile in a nation-under-construction, which is radically different from arriving in an established nation with its own needs being left unmet by a criminal political ascendancy. The Irish did not impose on anyone in arriving in the New World, but put their shoulders to the wheel to build it to become what it is today. Everyone who arrived there was there to work, to grow, to earn their daily bread or die in the attempt. They went to work building the countries of America and Canada with their bare hands — the ones among them who hadn’t died on the way, that is, only to face new hardships on arrival, which they embraced with a desperate hoping. They were not furnished with the latest Levis and Nikes, and billeted in five-star hotels. They were not given security details of armed thugs masquerading as police. They helped to build America, a fledgling, frontier nation, expanding into the wilds of a continent that had itself already been wrested from its indigenous peoples, a matter for intense ethical discussion, to be sure, but in no sense offering a parallel to what is happening in Ireland now, except in the sole sense that the perpetrators and their puppets will not allow: that the indigenous population of Ireland is today being genocided under multiple categories, and with the same objective.

Ireland is not unclaimed territory: it already belongs to the Irish people, who mostly remain, at least for now, but are being bullied and gaslit into not standing up for themselves and their children, and so are mostly intent upon lying still and fearful of being called nasty names. all the time hoping that this nightmare will cease and they will awake again in their land of heart’s desiring. In fact, rather than an expanding frontier society, Ireland is a society that has failed by every rational rubric to self-start, and therefore remains incapable of caring for its own, never mind inviting half the world in to steal what rightfully belongs to the progeny of those who built and preserved their country with their toil and sacrifices.

And by the way, who is the ‘we’ who are supposed to have ‘travelled all over the world’? Surely they mean ‘they’ — i.e., those who left Ireland’s ports many decades or centuries ago, and who are now either dead or, being themselves the descendants of the early settlers, ensconced in a different continent, are utterly unaware of their being used as blackmail fodder against their homeland and its people. Obviously, it was not ‘we’ who went, but the ancestors of people who were, as a result, born in Britain, or Canada, or America, and, living there today, are accordingly now Britons or Canadians or Americans. This is not a glib or minor point: the people who remained in Ireland and pulled it back up out of the abyss were our ancestors, who held faith with Ireland and fought to save her from perdition and the evil of interference from outside, most of the time on subsistence rations. They travelled to nowhere. They lived lives of deprivation and sacrifice so as to hand their country on in reasonable order to their children. We are those children, and we have the right to claim the inheritance they’ve left us, and hand it on to our own children, not to a bunch of grifters and moochers who have no loyalty to anyone but themselves.

To say or imply that a nation like the Irish should open itself up without limit or discussion is tantamount to saying that its people have no entitlement to a resting place in the world, no right to claim a birthright, no exalted right to the place where they, and their people before them, were born. It is to imply that their own children ought to be denied the basic entitlement of any human born on this planet: the right to call the part of the Earth on which he or she was born by the name of ‘home’, the right to put their heads down there with an easy heart, knowing this to be an irreducible right of any human being. This, above all, is what is being stolen here.

Another argument these vile ignoramuses proffer is that the West destroyed the countries of Africa, Middle East, et cetera, by its colonial adventuring, and so owes a debt to the descendants of those who were dispossessed. This is true, but, as The Vanishing Irish makes more than clear, Ireland had no part in any of that. The imperial overreach of England, Spain, Portugal or Belgium had nothing to do with us.

On the contrary, as is well known to others and ought to be manifestly clear to any person claiming Irish lineage, Ireland was itself occupied and colonised for many centuries by our nearest neighbour, and therefore has today more in common with the allegedly dispossessed countries whose citizens come to our shores in the 21st century demanding reparation than with the rest of the West. Isn’t that interesting: that the villains of history have somehow managed to arrange it that those who managed to recover somewhat from their attempted genocides should be the ones to compensate those who lacked the spirit or mind to save themselves?

I have referred previously to Douglas Murray’s superb 2017 book, The Strange Death of Europe, in which he sombrely describes a form of complicity by Europeans in the destruction of their own beliefs, traditions and legitimacy. We Europeans, he wrote, have forgotten that everything we love — ‘even the greatest and most cultured civilisations in history, can be swept away by people who are unworthy of them.’ He has in mind those among us who insist that European culture must roll over to give space to the incoming cultures. The myth of progress is used, he says, to blinker the peoples of Europe to the calamity unfolding in their midst. Europe is weighed down with guilt about its past, which paralyses even those who are blameless. And there is also, he says, a problem in Europe of ‘existential tiredness and a feeling that perhaps for Europe the story has run out and a new story must be allowed to begin’. This, precisely, is the condition that John D. Sheridan, writing of Ireland 1954, called ‘racial despair’.

Reading The Vanishing Irish, it is difficult to avoid the notion that this condition has in some mysterious way spread to the whole of Europe, as though by contagion from the Irish — that our condition is, in a sense, the original or earliest example of the disenchantment-with-self that bedevils the European peoples.

We are, then, travelling helter skelter from the 1840s — and indeed long before that — in an seemingly unstoppable trajectory in which not only the congenital inferiority complex of our race remains fully pervasive and rampant, but the methods in use against us — coercive plantation, moral blackmail, intimidation and propaganda — are but the latest forms of a strategy of ethnic cleansing that has pertained intermittently for hundreds of years. All that has changed is the emergence of new kinds of moralism directed at providing covering fire for these obscenities. Whereas the old coloniser merely asserted that he had come to a virgin territory in order to rape it for its own good — to bring it ‘civilisation’ and ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ — the neo-planters of the 21st century seek to project the sins of their ancestors on to the descendants of their ancestors’ victims, presenting themselves as though crowned by heaven with halos, their hearts bleeding from the observation of injustice and exploitation. The strange thing is how effective this strategy has been, as if it were not obvious that not one among those puffing up their chests about their obsession with catering for the world’s ‘most vulnerable’ have ever, even once in their benighted lives, exhibited the slightest public trace of human feeling for anyone without some manifest ulterior motive rooted in their own avarice and power-lust.

Should you consider the hypothesis outlined in this two-part series — and in particular its title, ‘Ireland: Birthplace of The Totalitarian’ — a little over-egged, consider the following:

That the radical policy of intimate policing initiated by Cardinal Cullen in the mid-nineteenth century ‘succeeded’ in maintaining Ireland at a rock-bottom population for more than a century, during which time its best and brightest were despatched as evangelists throughout the New Worlds, and the Old, to convert and condition and recruit, while the nation of Ireland withered and all but died. In a certain sense, that pattern was broken only twice, and both times relatively briefly — between the late 1960s and the late 1970s, and again in the decade approximately between the late 1990s and 2008, when two generations of Irish children were able to grow up in their homeland with the expectation of remaining. I was a member of the first of those two generations, and had the benefit of a political establishment which showed signs — uniquely in all the years of Independence — of understanding the concepts of human freedom and human self-sustenance, and who accordingly sought to build an economy whereby the indigenous population of Ireland might be able to pursue a material life by their own lights, and according to their needs, but otherwise be let alone by their government and tended to or interfered with only spiritually by their clergy. I write this with a lightish hand, but I believe it to be true: my generation — the late (post 1954!) ‘boomers’ — was the one with the highest representation among the dissenters from what happened in the spring of 2020.

The second period of apparent economic prosperity — aka ‘The Celtic Tiger’ — offered a form of freedom that ultimately proved false, for it sought to fool the Irish people into believing that they could farm out their country to outsiders and be free to do as they pleased — the very definition of the (non-existent) free lunch. On both counts, the Irish people were played like a fiddle at an All-Ireland Fleadh Cheoil, for the economy was never an Irish economy, and the freedom was of a kind that had to be paid for in other ways. Now we observe the culmination of those alleged years of boom and bloom: our country mortgaged to the hilt and laid low by the karmic forces that erupted inevitably from the radical collective breaches of the Natural Law that occurred in the past decade as a result of majority votes on matters that no right of choice can be said to exist. In 2020, it all started to come home to roost, as the alleged democratic government of Ireland began to foreclose on what had seemed to be absolute rights, so that soon it became clear that they would henceforth be ‘absolute’ only for outsiders who come like birds of carrion seeking a chunk of Ireland before the whole thing goes underwater.

In all this, sad to say, the Catholic Church played a nefarious role, in the first instance creating a model of totalitarianism that eventually outdid the best efforts of the British Empire for cunning and cruelty, in the second lapsing into silence and utter collaboration as the leaders of the political establishment turned rogue on their own people, closing the chapel doors and neglecting the spiritual welfare of their congregations in what was falsely purveyed as a deadly pandemic, and — worse — contorting their own Church’s teachings in order to bully the Irish people into accepting an invading army in the guise of refugees and migrants.

I was born in 1955, and by a blessing or fluke managed to grow up in my own country and live there for most of my life in freedom, sandwiched — had I known it — between two forms of totalitarianism, the first allegedly ordered by God, the second mandated by unelected alien powers. I barely noticed the last traces of the first totalitarianism — that initiated by Cardinal Cullen. By the time I reached the age of reason, it had all but disappeared. We got caned in school to the point of barely noticing, and there was a priest called Father Kelly, who had a habit of reaching out through the grill at the end of hearing your Confession and twisting your nose, but that was about the worst that we encountered. Subsequent history suggests that other categories of humanity suffered far worse consequences, and these matters are still in the process of outworking themselves, their issues and details being already well canvassed. Meanwhile, another totalitarianism has taken hold, and only a confident seer would, at this juncture, say whether it was likely to be worse or otherwise. And this time, yet again, the Catholic Church — once upon a time, though briefly, a rebel Church — has chosen to align itself with the forces of darkness, but now inviting upon itself the reasonable expectation of going down with the nation it once claimed synonymity with. Someone, somewhere, may claim a victory, but it is at this moment impossible to say who that might be.

To buy John a beverage, click here

If you are not a full subscriber but would like to support my work on Unchained with a small donation, please click on the ‘Buy John a beverage’ link above.