Inoculation against Vigilance

Outrage greeting comparisons between current events and past instances of man’s inhumanity to man may denote less respect for past victims than a desire to stop us speaking usefully about the present.

‘The past is never dead. It's not even past.’ — William Faulkner

The German philosopher Friedrich Hegel it was who said, ‘The only thing we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history,’ a charge that might bespeak amnesia or negligence or ignorance or, perhaps, inattention. But there is a sense in which it is even more true than Hegel may have intended: When the cultural context is constructed so that it is not merely difficult, or even impossible to learn from history, but actually forbidden, when certain events of the past, by virtue of being deemed unique, or uniquely sacred, or so definitively the experience of a particular nation, race or ethnicity as to be considered almost as the ‘property’ of that group, cannot be used for the purposes of contemporary comparison. In such situations, there is more than a tendency to reject all comparisons with the experience even by way of speculation as to their possible repetition, on the grounds of inappropriatness, or ‘disrespect, or even, in some sense, sacrilege.

This happens sometimes with colonialism, which is often claimed by racial activists as the experience only of certain ‘minorities’: black people, ‘people of colour’, and so forth. This is usually down to some mixture of ignorance and cynicism, and can usually be dealt with by advancing facts. But there is a more serious condition: when a particular experience has been genuinely unique up to the present, but is barred from being cited by way of comparison, association or speculation in any context because the ‘proprietors’ of that experience exercise a veto on its interpretation and implications. The Jewish experience at the hands of the Nazis in the 1930s and 1940s presents the most obvious example.

The sheer horror of these deeds, paradoxically, makes them harder to believe. All of us have seen and read many things that have shocked us to the core, even making us doubt that human beings could be capable of such evil. Statistics do not convey it, even pictures of mass graves are an abstraction of sorts. In 2015, at the time of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, a documentary titled Night Will Fall, a collaboration by British media mogul Sydney Bernstein and the legendary director Alfred Hitchcock — withdrawn in late 1945 because by then the allies had decided that rubbing the Germans noses in the Holocaust might be bad for the post-war reconstruction — was aired on British TV. The documentary shows some of the harrowing scenes that confronted allied forces when they arrived at Bergen-Belsen: the piled-up bodies of people executed by the Nazis just before the arrival of allied forces, as well as warehouses filled with human hair, toys, spectacles and false teeth — all taken from the victims before their obliteration, all carefully packaged and labelled. It is a strange thing that these assembled appendages of accoutrements of human existence seemed more definitively to convey the horror of what had happened than the all too familiar pictures of piled-up corpses. Perhaps what breaks our hearts most effectively is not the sight of dead bodies but the evidence of life’s traces remaining when it has been extinguished.

Part of the proffered rationale for the suppression of the documentary was an attempt to staunch the backlash against Germany arising from what, in the aftermath of the war, was emerging about the Nazi period. This suppression coincided with the start of a concerted attempt to transmit the idea that the Holocaust ought to be seen as a crime of the human species rather than of Germany per se, arising a previously undetected pathology of humanity that just happened to materialise where and when it did. And yet, one of the consequences of this strategy was to unleash the countervailing idea that the Holocaust was some kind of insoluble mystery, that it was impossible to understand how human beings could behave like this, that the episode was some kind of one-off aberration involving one bad man, or bunch of bad men, and that, somehow or another, a recurrence of such evildoing, being inconceivable, was unlikely. This had a peculiar effect within Germany itself, solidifying the sense of national guilt while driving it underground, into the collective unconscious of the nation, incapable of being talked about and therefore immune from deeper understanding. The desire to relieve Germany of its shame in order to restart the world may therefore have rendered it impossible for a fuller cultural understanding of Nazism to emerge.

After Nazism, the world almost instantly reverted to thinking of evil as belonging to exceptional circumstances and unique categories of human being. Today, we think of Hitler as a demon, and have some vague sense that he somehow hypnotised a whole nation to fall in or turn blind eyes. But there persists minimal cultural awareness of the dynamics by which Nazism operated. After the war, the imperative of ‘peace-making’ rapidly imposed another kind of wound: an injured memory proffering little clarity as to how the greatest crime in the history of the world came about. The world, including Germany, filed the Nazi era away as an anomaly of history, a Hollywood story of classic baddies with bad moustaches, but with nobody surviving on whom any significant burden of blame might be imposed.

A strange ricochet of these developments was that gradually there emerged a form of thinking whereby any attempt to extrapolate meanings and connections from the context of what had occurred in Germany — or in Russia and Eastern Europe in the decades immediately before and after — would be deemed improper, disproportionate and inappropriate. This meant, in effect, that it would become impossible to detect signs of similar phenomena emerging in the future, despite the very strong conviction that emerged in the 1950s that these totalitarian phenomena represented a new development with roots in the nature of modern society. In due course, these tendencies came to be augmented by another: the refusal of the victims and descendants of victims to permit the experience of, in particular, Nazism, to be drawn upon on for the purpose of constructing hypotheses or comparisons concerning events in subsequent times.

Last year, speaking to the media outside Leinster House, the Tipperary TD, Mattie McGrath, made a comparison between the Jewish experience of Nazism and some aspects of Covid ‘measures’. Speaking about the introduction of ‘vaccine passports’ in July, he asked: ‘Is that where we've come to now, back to 1933 in Germany, we'll be all tagged in yellow with the mark of the beast on us, is that where we're going?’ The Taoiseach challenged McGrath in the Dáil about his comments saying: ‘I think you should refrain from your frequent use of language and I've asked you to stop using terms Nazis and totalitarianism. You've made ridiculous assertions in this house and that are offensive to people. You have repeatedly accused the government of being like Nazis, in this house.’

Mr McGrath asked to be spared the history lesson, not necessarily the best answer. What Martin had delivered was not a history lesson, but a demonstration of political bullying and evasion. McGrath may not be a debater of the first rank, but he was saying something brave and necessary. What Martin was saying sounded like a righteous response, but only because he followed the slipstream of a well-established truism. Minister of State, Thomas Byrne, joined him in kicking McGrath, saying: ‘Nothing, absolutely nothing, compares to Nazi Germany. Every comparison made diminishes the memory of that unique evil, and the slaughter of millions of Jews.’ This is the kind of thing that might get you a round of applause on the Late Late Show, but that does not qualify it as a moral response. Nazi Germany remains ‘unique’ only for as long as it remains unrepeated, and what McGrath was implicitly trying to do was postpone the moment of repetition indefinitely.

Interestingly, soon afterwards, to the chortling of journalists, Mr McGrath found himself the subject of a rebuke from the Auschwitz Museum, which tweeted: ‘Instrumentalization of the tragedy of all people who between 1933-45 suffered, were humiliated, tortured & murdered by the hateful totalitarian regime of Nazi Germany to argue against vaccination that saves human lives is a sad symptom of moral and intellectual decline.’ This, on its face, may have seemed to level a legitimate charge of disproportionality against McGrath. There are not, after all, six million corpses to be pointed to in evidence. ‘Holocaust’ is a word that ought to be used sparingly, not due to any etymological factor but because it has come to be used in a particular, sacred context and therefore ought not be trivialised.

But is that really the end of it? Mattie McGrath did not use the word ‘Holocaust’. Nor did his point relate to a comparison between the Jewish experience and vaccination per se, but to the use of ‘vaccine passports’ — a recent and unprecedented instrument in supposedly free and democratic societies — to restrict the freedoms of people who exercise their right to make decisions about their own health. His argument might be said to have drawn a comparison not with 1933 but with September, 1941, when the Nazis introduced the yellow Star of David to identify Jews in public, though interestingly this moment almost precisely coincided with the building of the first Nazi gas chamber, in Auschwitz. Perhaps more germanely, vaccine passports were introduced in Ireland in respect of a ‘vaccine’ that is not a vaccine (a gene therapy, actually), that is unnecessary, does not work in the manner claimed by its manufacturers and pusher-governments, and has already been shown to cause death and damage at levels far beyond which previous vaccines have been withdrawn.

Nor, in a climate of almost total censorship and suppression of critical voices, is it clear, even by the crudest interpretation of risks-benefits analysis, that there is any evidence that these ‘vaccines’ have ‘saved human lives’, as the Auschwitz Museum tweet asserted. This claim, devoid of evidence, is merely a tendentious repetition of government propaganda. It is well established that people are being killed by the Covid ‘vaccines’ — something in excess of 3,000 in Ireland alone, the equivalent of the death toll in 30 years of the Northern Ireland Troubles, in just 12 months. The global figure, calculated on a pro rata basis, would be several million. In the US, even the conservative official statistics acknowledge some 21,000 deaths. In Europe, the European Medicines Agency — again, a conservative witness — had by late-November 2021 admitted to 30,551 vaccine-related deaths, and 1,163,356 adverse reactions. That’s a lot of human hair, spectacles and false teeth; and now they propose to start work on the depository of toys.

Mattie McGrath did not set out these facts, but nor was he seeking to insinuate a comparison between the Holocaust and Covid vaccines. His point was a narrower one: that the requirement to produce documentary proof of vaccination in order to access basic services was analogous to the process that remains one of the dark hallmarks of the Nazi regime. As such, it was entirely valid, and would have remained so even if it was incontrovertibly established that these ‘vaccines’ had saved lives, which is, as it happens, the contrary of the truth.

In rebuking him, fellow politicians and the Auschwitz Museum were trading off an established aura of reverence that surrounds the Jewish experience of Nazism. It is not necessary to question the validity of this reverence in order to establish that McGrath’s commentary was valid in as far as it went, and that, although his remarks might well have sparked a heated debate (albeit one that was closed down peremptorily), his intervention was long overdue in circumstances where we had been labouring for 16 months at that point under the draconian laws imposed by the political system he is part of. McGrath ought not to have been subjected to reprimands grounded in the calamity of six millions dead people. That was disproportionate.

When Minister Byrne said that ‘nothing, absolutely nothing, compares to Nazi Germany,’ he really meant that nothing in the present or future can compare to it. But is that valid? How can we know? Is it the case that ‘every comparison made diminishes the memory of that unique evil, and the slaughter of millions of Jews.’ Do we need to have millions of corpses to be entitled to warn against the possibility that totalitarianism might resurface? Must there be gas chambers too? Gulags? Quarantine camps clearly won’t be sufficient, even while they provide an ominous echo. Are even these observations likely to be deemed ‘offensive’? Isn’t that just a little convenient?

Tyranny, torture, murder — these, surely, are the dangers we need to watch for? In the past two years we have had, undoubtedly, tyranny. Torture? Well, there are many kinds: torture of minds counts also, the torture of the elderly left to die alone in their beds. And murder? Read Denis Rancourt’s devastating analysis of the death patterns of Covid. And are there not other things we might usefully watch for also? The pursuit of Utopias, those ‘Perfect Societies’? Life without death? Messianism? Building Back Better? The denial of the human person’s right to decide his own level of risk, thereby depriving him of everything that makes his life worthwhile? The staking of human lives in medical experiments? The drift of politics towards power of dangerous kinds? Disrespect for humanity is always worrisome, as is the tendency to cover up inconvenient outcomes even as they grow more glaring and ominous. Our pograms are so much more civilised now, what with Midazolam and ventilators and mRNA spike proteins, but still they lack something in verity and transparency. No greater evils have ever been designed than those designed by those who imagine they are doing good. And there is, as Orwell observed, a tendency for stories of atrocity and cruelty to resemble one another.

The — until now — metaphysical singularity of the Jewish Holocaust experience does not need to be argued for: It is self-evident on the basis of the facts as historiographically established and handed down. Nothing of that is in dispute here. The question to be addressed relates to whether that singularity is absolute or contingent, and , in the event that it is not absolute — i.e. not incapable of repetition — whether there can be any entitlement of any individual, group or body to gatekeep its meaning in the manner that, for example, the Auschwitz Museum sought to do with Mattie McGrath.

Two years ago, the German journalist and editor in chief of CATO magazine, Andreas Lombard, wrote a remarkable essay, The Vanity of Guilt, for First Things magazine about the way his country had become haunted to the extent of self-abnegation by the deeds of the Nazis. His immediate context was post 2015 mass migration but his theme was guilt: ‘In the decades after 1945,’he wrote, ‘the imperative of forgetting was succeeded by the imperative of remembering. Victims replaced heroes, and remorse and self-accusation superseded pride.’

Germans were required to remember their guilt and shame, and could no longer stand up for their nation or themselves. This was the tragedy of twentieth-century Germany: that to make it clear it did not wish to harm anyone, it had to harm itself.

He went on: ‘This dynamic is pathological, viewed sociologically. But worse, it reflects a vanity of guilt that is dangerous and destructive in its theological arrogance. To a striking degree, the German political and cultural establishment has taken possession of the Holocaust. This terrible crime has become a precious asset to be deployed against anyone who dares to criticize the status quo.’ Guilt can be employed as a weapon and used to bludgeon even the guiltless into silence.

In its aftermath, he elaborated, the Jewish Holocaust was treated as if it could prevent other crimes against humanity, if only it could be kept in the collective memory. ‘By calling our evil constantly to mind, we would negate its power.’

But, instead, he said, the commemoration of the Holocaust has created ‘a hubristic self-righteousness’. Germany had ordained itself a unique destiny of self-abnegation. And this, in turn, had been used — by Germany! — to accuse others by way of anticipating their tyrannies, their fascisms, their potential for Nazism. One of the obligations Germany seeks to impose on others in this way is the obligation to no longer protect their own borders. Because of Germany’s prior treatment of the Jews, German leaders assume that ‘negative nationalism should be obligatory for all of Europe and the world of tomorrow.’

Perhaps what he described here was an inevitable consequence of the particular kind of ‘remembering’ that was permitted in the wake of the Nazi period. On the one hand, Germany had to remember; on the other, we should not rub its nose in the past. On the one hand, we needed to make sure that such things could never be repeated; on the other we were not permitted to cite the Nazi period in any attempts to alert our fellows to any such particular danger except a nationalist one.

The energy for the insistence on ‘negative nationalism’, he said, derives precisely from the metaphysical singularity of the 1930s/1940s Jewish Holocaust. This principle states that this Holocaust is the greatest crime in history, and will always remain so. Its evil can never be surpassed. Or indeed equalled. But, strangely, he notes, it is usually non-Jewish Germans who make this claim.

‘There is something suspicious about this,’ Lombard expands. ‘Germans claim singularity not as victims, but as perpetrators. The “perpetrator people” now exalt their own crime as the greatest in human history — a monstrous kind of negative pride. The accused steps up to become the supreme judge. The point is not what verdict he renders, whether it is acquittal or conviction. The point is his hubris, a hubris he conceals behind the verdict of maximum guilt.’

A metaphysically singular crime, Lombard says, can never be forgiven or forgotten. Reconciliation is impossible. But the twist in the tail is that it is the German refusal to ask for forgiveness that most of all makes this withholding of absolution inevitable. And as with Germans, so also with Gentiles.

The discussion of Nazism is managed, and not necessarily in a straightforward direction. We are permitted to speak of it if our objective is ideological opposition to nationalism. We may use it to condemn neo-Nazis, and ‘far right’ politicians, and, somehow or other, ‘white supremacists’, but not as a cautionary tale to place a check on the adventuring of mainstream, everyday politicians in the present.

Nazism, in the context of its permitted leveraging, cannot be forgiven, but nor can it be repeated, other than in certain contexts. And nor can it be referenced by those seeking to issues warnings about the possibility of its repetition in other contexts or in a general fashion. The franchise of the crime is protected not just by its victims but by its perpetrators also. The idea that nothing compares to Nazi Germany, and that every attempted comparison diminishes the memory of ‘that unique evil’ is sufficient to prevent constructive lessons being adduced from that experience.

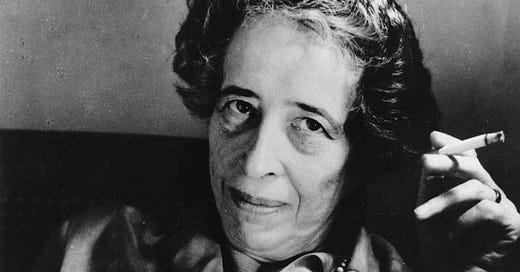

Perhaps the most comprehensive documenter of the totalitarian tendency has been the brilliant German Jewish philosopher, Hannah Arendt. In her definitive deconstruction, The Origins of Totalitarianism, she describes in forensic detail the operation of the Hitler and Stalin regimes, including the events and processes leading to the Jewish Holocaust, which she characterised as an entirely new phenomenon of the twentieth century. Arendt was not concerned with the particularities of German fascism or Russian communism in some general sense, but with the particular forms of government developed under Stalin and Hitler. Her main focus is on Nazism — being herself German, with direct experience of the Nazi model, but also because, whereas Hitler was dead at the time of her writing, Stalin’s reign of terror was to continue beyond her book’s first publication in 1951.

In writing what became that first edition of her book between 1945 and 1949, Arendt was at pains to stress that totalitarianism was not simply another form of tyranny, but a unique and novel development — the total domination of a people through a combination of simplistic ideology and constant terror — and yet, with the dark paradox: totalitarianism ultimately rests on mass support. She set out seeking answers to three questions: What happened? How did it happen? How could it have happened? She had access to ‘mountains of paper’— ‘a superabundance of documentary material on every aspect of the twelve years that Hitler’s Tausendjähriges Reich had managed to last.’

Arendt, then, saw totalitarianism as a complex, subtle, unprecedented process, with a beginning, middle and a destination: total control. The destination could not be understood without the beginning or the middle, and the beginning was the foundation upon which the middle and destination phases were constructed. It is also clear that she saw herself as treating of a ‘form of government’ with clear indicators as to its emergence, which was responsible in the twentieth century for not only the deaths of six million Jews, but for upwards of 100 million deaths all told. Let us not forget that Hitler killed far fewer people than Stalin, and both of them together far fewer than Mao. But it seems that you need to reach Mao’s level in our culture to have a restaurant named after you.

Our reaction to Nazism is more visceral than our reactions to the other totalitarianisms, but we ought to be cautious rather than smug on that account. Is it the numbers that offend us, or something else? That ‘something else’ certainly existed in Nazism: machines for killing, not just killing as a collateral consequence of some other inhumanity, but killing for killing’s sake.

In the course of her forensic profile, Arendt details many of the arcane and unexpected aspects of the phenomena under her microscope. For example: the differences between fascism and totalitarianism; the totalitarian project of terrifying human beings ‘from within’; the differences between ‘the mob’, ‘the masses’ and ‘the elite’; the mob as caricature of the people’, the ‘masses’ as an amalgam of ‘neutral, politically indifferent people’ who could not be incorporated into any form of organisation; the totalitarian leader as a functionary of the masses he leads; how totalitarianism uses threats of exclusion to terrorise people into line; the use of propaganda to convert prejudice from a mere opinion to a ‘principle of self-definition’; ‘the terrifying roster of distinguished men whom totalitarianism counts among its sympathizers, fellow travelers and inscribed party members.’

Arendt says that the Nazis inverted the commandment ‘Thou shalt not kill’ to ‘Thou shalt kill’. She also notes that they remained observant of certain laws. They were not indiscriminately evil. They played ‘fair’ but within their own, self-made rules.

The central plank of totalitarianism is the pursuit of terror. What was ‘attractive’ in this for its adherents was ‘a kind of philosophy through which to express frustration, resentment and blind hatred’. It was a way of forcing recognition of individual existence on the whole of society — by negating individual uniqueness.

The ideology of totalitarianism is directed at world domination, and its chief instruments are terror and the creation of a pseudo-reality in which to forge a cultlike mentality, embracing a majority but excluding a designated and delineated group. Surveillance is therefore central to the administration of the totalitarian system, and to the orchestration of terror and resentment among both elements of the divided population. Arendt identified three core elements in the totalitarian ideology: the claim to ‘explain’ the future as a fixed reality; the directing of the population as to the correct form of thinking and responding; and the freeing of human thought from experiential logic and spontaneous reason, which are supplanted by the singular idea on which the totalitarian movement is founded.

In the present case, if we may dare to observe so, the central ‘totalitarian idea’ is that of permanent emergency, which is to say the postulation of maximum imputed safety at the expense of freedom qua freedom.

The issue that Mattie McGrath touched upon — the requirement to carry, and produce on demand, identification papers — is a mechanism for destroying individual autonomy, for it posits by implication that each individual is merely a singular quark, answerable to the whole via the state. It is a way of conveying an insult by the state to the very idea of the particular human person, never mind the sovereign human person. By conveying an implicit suspicion, it conveys also a dualism — state v. citizen — and a hierarchy of power that is primed with terror. Surveillance and monitoring of individual identity are also, in a totalitarian state, the preserve of the secret police, one of the chief instrument of state terror, whose job it is to monitor and eliminate the internal enemies of the totalitarian movement.

Surveillance exists not just for its own sake — for reasons of security or intelligence-gathering — but as an instrument of intimidation and levelling, of reducing each member of the mass to a state of terrified interchangeableness. The point of this, as Arendt outlines, is to ‘make all men superfluous’ — ‘individuality, indeed anything that distinguishes one man from another, is intolerable.’

‘Total power,’ she adds, ‘can be achieved and safeguarded only in a world of conditioned reflexes, of marionettes without the slightest trace of spontaneity. Precisely because man’s resources are so great, he can be fully dominated only when he becomes a specimen of the animal-species man.’ The purpose is to atomise the population, each citizen from each other — or, rather, to further atomise them, since our technical society, as so brilliantly illuminated by Jacque Ellul, has already done most of the heavy lifting for the pathocrats.

Isolation and atomisation are also the true purposes, in the present context, of face masks and ‘social distancing’: to convey to each citizen that he is alone except as an atom of the mob, and as such interchangeable with each other ‘atom’.

Arendt eventually emerged with a detailed profile of a form of government that appealed to no traditional laws or existing forms but rather to its own concocted Law of Nature (survival of the fittest, master race) or Law of History. Its goal was the extension of that total domination to the entire world. In totalitarianism, she described, all traditions, values, legalities and defences, all political institutions are destroyed, and all behaviour, public and private, comes to be controlled by terror, which becomes the measure of all things. Her central thesis was that great evils are not carried out by individual monsters, but by ‘ordinary’ or ‘regular’ people, many of whom become convinced of being involved only in nondescrip actions. In order to convince regular people to carry out atrocities, it is not necessary or useful to fill them with hate but simply to normalise and desensitise them to what would otherwise be considered unthinkable.

These fundamentals are of immense interest to us in our present situation, transcending any symptomatic differences between the then and the now. Must we wait for the evidence to pile up in the form of human corpses before we apply our minds to formulating meanings for things that strike us as peculiar or disturbing? If so, is there an acceptable level of carnage to be exceeded, before we are permitted to note the early signs of a testing of the values of our civilisation? Must we seek permission from the alleged representative of those who suffered previously from the conditions seeming to be incipient in our own time? Are we to avoid obvious similarities lest we cause offence? At what point, if any, would it become permissible to hazard a comparison? Is politesse more important than vigilance? How are we to be certain that such a culture of deference is not being constructed and manipulated by the same kinds of individuals who once manipulated the German or Russian peoples?

‘Totalitarian regimes,’ wrote Hannah Arent, ‘discovered without knowing it that there are crimes which men can neither punish nor forgive. When the impossible was made possible it became the unpunishable, unforgivable absolute evil which could no longer be understood and explained by the evil motives of self-interest, greed, covetousness, resentment, lust for power, and cowardice; and which therefore anger could not revenge, love could not endure, friendship could not forgive. Just as the victims in the death factories or the holes of oblivion are no longer “human” in the eyes of their executioners, so this newest species of criminals is beyond the pale even of solidarity in human sinfulness.’

Must it come to this again before we are permitted to speak?

‘It is inherent in our entire philosophical tradition,’ she continues, ‘that we cannot conceive of a “radical evil,” and this is true both for Christian theology, which conceded even to the Devil himself a celestial origin, as well as for Kant, the only philosopher who, in the word he coined for it, at least must have suspected the existence of this evil even though he immediately rationalized it in the concept of a “perverted ill will” that could be explained by comprehensible motives. Therefore, we actually have nothing to fall back on in order to understand a phenomenon that nevertheless confronts us with its overpowering reality and breaks down all standards we know. There is only one thing that seems to be discernible: we may say that radical evil has emerged in connection with a system in which all men have become equally superfluous. The manipulators of this system believe in their own superfluousness as much as in that of all others, and the totalitarian murderers are all the more dangerous because they do not care if they themselves are alive or dead, if they ever lived or never were born.

It is clear from these quotations that Arendt believed that the ‘radical evil’ of Nazism was something new in human history, but that it was not going away again. She saw it as a matter of urgency that humanity should begin to comprehend this and to become watchful for its signs. She was not suggesting that the crimes of the Nazis were ‘unique and unrepeatable’ but something like the opposite: that their uniqueness at that moment offered humanity a warning that, if heeded, might serve to prevent a recurrence of those horrors. She resisted early attempts to ‘generalise’ the Holocaust out of its German context. In an exchange with the German writer Hans Magnus Enzensberger she repudiated the suggestion that the mass killing of Jews was but one ‘holocaust’ among others. She had been dismayed when Enzensberger seemed to suggest that Nazism was not especially a German thing, but could happen anywhere — i.e. Nazism was a species-shaming phenomenon rather than a specifically German pathology. Arendt baulked at this, but chiefly, it seems, because it smacked of an attempt to exculpate the wrongdoers in her own country; had she not done so, she might herself have been open to charges of spreading the shame. In due course, she was to refine her argument into what has become one of the most penetrative phrases in all of philosophy’s efforts to comprehend evil: the banality of evil.

In her magisterial 1964 book, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil — her reportage and analysis of the trial of the Nazi bureaucrat Adolf Eichmann — Arendt profiled the archetypal functionary of the Nazi era. In writing it, she was at pains to stress that the pathology to be found in Eichmann arose in the specific setting of the totalitarian state established in Germany by the Nazis, and yet encapsulated the personality of the evildoer as an embodiment of everydayness.

In her writings about Eichmann, Arendt delved deep into the question of evil as the potential reflex of ‘normal’ people. Although the world, including Germany, has managed to file the Nazi era as a kind of Hollywood-scripted conflict of bad guys and good guys, under Arendt’s unremitting microscope it becomes something like an inevitability of a highly-developed post-Enlightenment, literate, self-referential, atheistic culture, in which there are only the laws created by the state. Nazism, we would prudently remember, unlike Bolshevism or Stalinism or Maoism, emerged in a ‘modern’, technocratic, democratic state.

Eichmann, as observed by Arendt, presented a new kind of problem. He was not ‘evil’ in the conventional sense, but in what seemed to be a novel way. He was evil, and yet he was also normal. His evildoing was of an everyday kind, yes, but more than that, his evil derived from his ‘normality’. That meant that the kind of things he did might well be done by anyone. It might even mean that the more ‘ordinary’ the individual, the more likely he is to perpetrate such evils. Arendt noted, for example, that Eichmann seemed incapable of uttering a single sentence that wasn’t a cliché. His evil arose from his denseness, his inability to think, which is to say his inability to engage in a dialogue with himself. He uttered only words given to him by others. Another way of describing this might be to say that he was a man without a self, without an ‘I’. He could only converse with himself in a language imported from outside, in a voice belonging to the world beyond himself. He had no internal sense of the absolute. His ‘absolute’ consisted in his duty to do what he was told.

‘The sad truth.’ Arendt wrote, ‘is that most evil is done by people who never make up their minds to be good or evil.’

This is the great value of Arendt’s work, and also the reason why we need to pay more rather than less attention to the particularities of the Nazi period: so that we may better understand them, so as to more easily spot them in other contexts, so as to turn ‘never again’ into a fact rather than a cliché. Perhaps one of the motivations behind the idea of sacrilising the Holocaust is to conceal these possibilities from ourselves. Perhaps we fear that we cannot look squarely at Eichmann, the most ‘ordinary’ Nazi, because we fear that we might see ourselves. We shy away and leave the question as open or closed as it has always been. The ‘banal’ dimensions of evil remains distant, mysterious, because we became convinced that it remains unthinkable, which of course it does, though only because we choose not to think about it. This allows us to continue to believe that evil people are exceptional types of humanity, when in fact they may be almost the opposite: unexceptional to the point of dullness.

Is it not, then, to say the least, counterproductive to allow that experience and Arendt’s insights into it to be fenced off from reality and stewarded by interests which, whatever their claim of entitlement to emphasise the Jewish wound, have no such right to block humanity from identifying early indicators of similar syndromes erupting in other contexts, and underscoring the parallels with prior events by way of alerting their fellows to the possibility of a looming recurrence.

Arendt’s point was not as in the conventional response, at once exculpatory and hand-wringing: We are all guilty. If we are ‘all guilty’, then perhaps nobody is guilty? Is this the destination point of our courtesy towards the vitims of past tyrannies? It is tempting to suspect so. Her point was that we are all capable, and therefore need to be on the lookout for early signs. It would therefore be foolish to allow ourselves to become blocked off — above all by ideological interests — from studying and rehearsing the lessons of history, or waylaid by dint of condescendingly imagining that our times have somehow (being too ‘advanced’, too ‘modern’?, too ‘enlightened’) risen above such potentialities, entitling us to ignore the recurrence of signs and drifts that preceded the world’s previous descending into the abyss.

Hannah Arendt was one of the great prophets of the twentieth century. She did not intend her books to be adornments on future smugness, or fossilised records of past barbarism. She intended them as warnings — as much to future peoples as future leaders. No one — no one — has the right to claim the history she excavated so brilliantly and claim to have the franchise on its exclusive interpretation. You might say that Mattie McGrath’s comparison was . . . what? Lacking in proportion? Facile? Or perhaps banal. Perhaps that is precisely why we need to hear it.

Andereas Lombard, in his First Things article, cites Hannah Arendt: ‘This guilt [of the Nazis] in contrast to all criminal guilt, oversteps and shatters any and all legal systems. . . . We are simply not equipped to deal on a human political level with a guilt that is beyond crime and an innocence that is beyond goodness and virtue.’

This was an understandable responses in the moment that Hannah Arendt wrote those sentences. What had happened was radically different to anything that had happened before. But the very nature of Arendt’s exploration, in particular with regard to Adolf Eichmann, opened up the very real possibility that such evil might henceforth become commonplace. There is a paradox here, then: She was alerting us to the nature of the unprecedented crime that, by virtue of occurring, could never again be regarded as unthinkable. What, now, might be the barrier, if barrier there might remain, to the Nazi crime being replicated or equalled or surpassed in its evildoing and consequences? One answer might be that the barrier or guarantee against recurrence resides in memory, in commemoration, in a determined refusal of amnesia. But if that remembering is constrained by an insistence that what is commemorated can never recur, then is this condition not counter-productive to the entire purpose of remembering?

What is it that validates the claim that the guilt of the Nazis will always remain ‘beyond crime’? The methods of extermination? The number of the dead? Hitler’s retroactively and tautologically repulsive moustache, which has become an exclamation mark in history? Is there a moral difference between a big moustache and a small one, or isn’t that just a trick of looking through the wrong end of the telescope of Time? And can we not imagine a parallel reality in which that space-saver moustache might have become the height, if not the breadth, of fashion? (All it would have taken was for Germany to win the war and a few more years to have passed – if you doubt this, consider: Sinn Féin.)

Is it possible that the Devil will contract only to manifest in forms that announce themselves as crude depictions of the evildoer? Do we think that all villains will laugh to announce themselves like the ones in spaghetti westerns? And if the evil of totalitarianism is deemed to be a peculiar eruption of the twentieth century, is there any reason to assume that its arc will not increase rather than the opposite?

Would it be necessary for our corrupted, power-crazed, sadistic leaders to parade in a row sporting Hitler-style moustaches before we could consider them capable to comparable crimes? Would mortality figures alone be insufficient? What about mass euthanasia? White coffins? What?

Yet, our culture now insists that it is so: We must not invoke the Nazi story, for to do so is by definition disproportionate and therefore disrespectful. It is, we are assured, unthinkable that anything remotely similar could be perpetrated by mild-mannered politicians in shiny grey suits, which opens up the odd circumstance that such politicians are about the only people who might nowadays, in present geopilitical conditions, attain the kind of power and opportunity to carry out such obscenities. But to seek by analogy with the conditions of 1930s Germany to warn of such a prospect is regarded as an improper appropriation of the Greatest Crime in History.

Can any of this be what Hannah Arendt intended to suggest? I think not.

In his 2019 First Things article, Andreas Lombard’s central point was that the vanity of guilt leads to an inability to court forgiveness, either from your victims or from yourself, and this stymies the possibility of healing. This is important, and not irrelevant here. But more immediately vital is an understanding of how the power of the Metaphysically Singular Crime — perhaps ‘crimes’, since apartheid, colonialism, witch-hunting and slavery have, in certain (somewhat less fevered) ideological contexts, attained something like a comparable level of historical holiness —can be used to protect the perpetrators of potentially comparable crimes in the early days of their criminality. To deflect insinuations of similarity, and the attendant possibility of the alarm being successfully sounded, all the would-be tyrants need do is express outrage at the inappropriateness of the comparison and protest volubly at the implicit insult to those most grievously wronged by the prior crime insinuated as a comparator. Their accusers, who have sought to weaponsise an unsurpassable crime, are instantly deemed far worse than those they accuse, even if their worst prognostications were to be vindicated.

This creates not just a block on remembering but a kind of inoculation against vigilence. It means that the would-be criminals can turn the charge back on their accusers, who then become the true offenders, the sacrilegious opportunists who tried to misappropriate the Holocaust, apartheid, witch-hunts, the experience of slavery, et cetera, to a nefarious end. Thus, the putative (would-be?) perpetrators of comparable crimes are able to achieve immunity from criticism, or even general scrutiny, until late in the day — until, perhaps, it is too late to put a stop to their galloping. The only evils deemed to be capable of repetition are of the lesser-spotted type, and even these cannot be described or anticipated in the language that has already been used to describe the Metaphysically Singular Crime(s). Thus, the facts of Nazism, Communism, Imperialism, Neo-colonialism, become a kind of insurance policy against comparison. Rather than a guarantee against a recurrence, the greatest evils in history become prophecies of what has yet to befall us.