Desmond Fennell and the Politics of Error

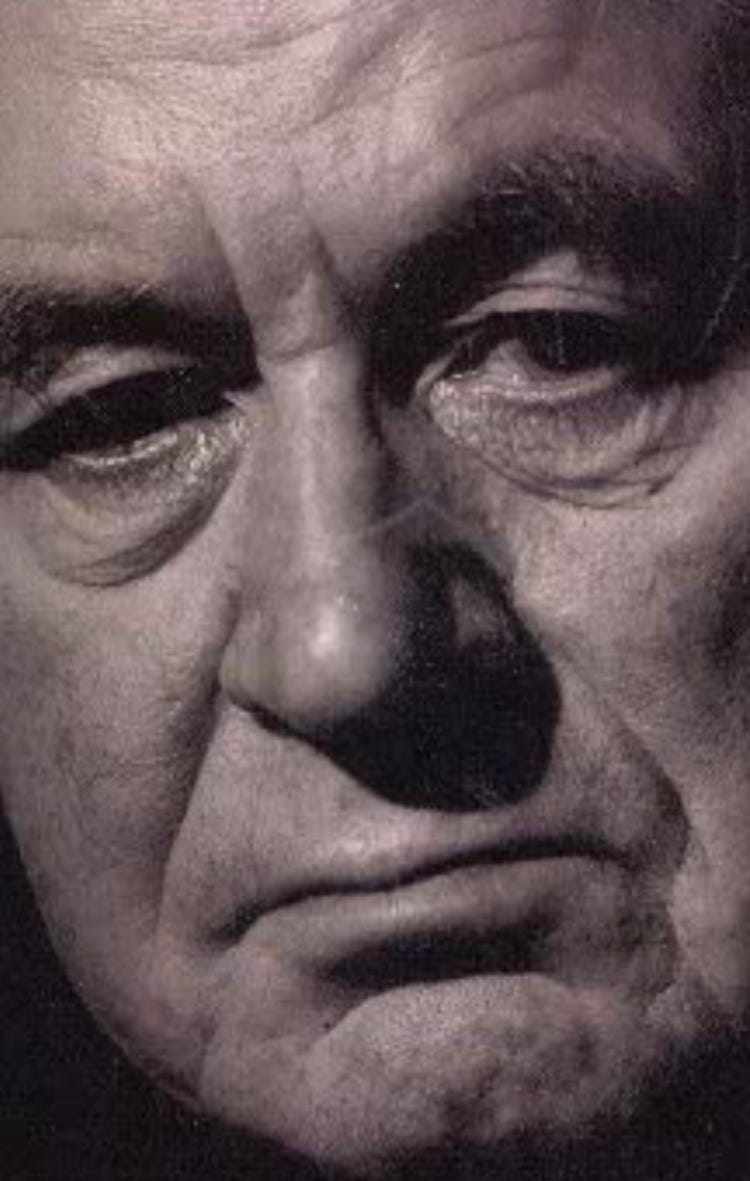

Desmond Fennell, who died last week, was the most brilliant thinker to emerge from 20th century Ireland. More accurately than any other, he anticipated the senselessness in which we live now.

(A chapter included in Desmond Fennell: His Life and Work, a 2001 compendium of reflections and assessments, published by Veritas and edited by Toner Quinn.)

In the early months of the new millennium, while talking one day on the phone with Desmond Fennell, I gathered that he was a little disgruntled about something. He explained that he had written an article for a national newspaper — the content of which I do not recall — and the editors had made a number of changes to the text without consulting him. He was particularly annoyed because he had been scrupulously careful to stay within the designated word-count, so as to avoid providing any excuse for interference with the article. He found the incident most uncivil, he said, as well as frustrating and not a little embarrassing. The piece, as printed, did not convey what he intended, having had its meaning altered by the changes. Moreover, he suspected that the changes had been made for ideological reasons by someone working in the newspaper who disagreed with him. I agreed that the incident, as he described it, seemed both uncivil and journalistically unforgivable, but then I enquired further into the nature of the changes, which as I recall related to the expression of some clearly unfashionable view, with which Desmond is well endowed.

On hearing what the changes were, I immediately saw what had occurred. I explained to Desmond that what he had described was not, as he suspected, an incident of ideological sabotage. It was simply the newspaper exercising its editorial judgment in an instance where one of its contributors had been observed to be wrong. But, he protested, the change related not to an issue of fact but a matter of opinion. He had simply stated something which he, on the basis of the analysis he was outlining, believed to be true. That is as may be, I replied, but it was still wrong. What had occurred, I guessed, was that a senior editor or sub-editor, on reading his article, had realised that one of Dr Fennell’s beliefs was actually incorrect, and had altered it to save embarrassment to both the author and the newspaper. There was no ideological agenda, no conspiracy, no lack of civility. On the contrary, the change had been made to protect Desmond Fennell from the consequences of his own error. He could hardly argue, I pointed out, that a newspaper was not entitled to prevent wrongheaded views getting into its columns. The fact that what he had written was his sincerely-held opinion based on several decades of contemplation and observation was neither here nor there — he was as wrong as if he had carelessly alluded to Christmas Day falling on June 23rd.

Unfortunately, Desmond Fennell’s work is littered with such errors. For example, his book Heresy: The Battle of Ideas in Modern Ireland, even before it begins, carries the dedication: ‘To Bernadette McAliskey with respect’. This is almost certainly a mistake. If such a dedication were to be attached to an article for a national newspaper in Ireland, it is absolutely certain that it would have to be removed to protect the author’s credibility. Clearly, if he had been thinking correctly, he would not have written such a thing. He is, after all, an educated man. What could he be thinking of? To associate himself with a woman who is herself not merely wrong about everything, but even dangerously wrong, was surely an act of extreme foolishness. But it doesn’t stop there: On the very next page is reproduced a quotation: ‘One loves the freedom of men because one loves men. There is therefore a deep humanism in every true Nationalist.’ The author of the statement was Padraig Pearse. Clearly, again, both the sentiment and the choice of it are ill-advised. Desmond Fennell obviously does not know that nationalism is not something which right-thinking people should have to read about other than in a pejorative connotation, and the same goes for Padraig Pearse. If such a quotation were to appear in a newspaper article, it would cause those who run the newspaper to have hurried consultations concerning the wisdom of having people like Desmond Fennell write any further articles. But perhaps if the reference could be deleted and Dr Fennell were to make no protest about the excision, there might exist some hope for his rehabilitation . . .

Growing up and into the ferment of ideological debate which has provided the intellectual infrastructure of what is termed Modern Ireland, it was difficult to know precisely what to do about Desmond Fennell. On the one hand, he was clearly a deeply reactionary individual, a man with what appeared to be a benign interest in the welfare of Catholicism, Nationalism and other elements which had been placed in the loading bay awaiting removal from the premises. While the rest of us were busily tying up the boxes and moving the skip into place, Desmond Fennell was moving obliviously through the boxes, reopening them, pulling out their contents and making notes. Occasionally, he would pause and make a statement or ask a question. ‘Have women souls?’ he would ask, puffing on his pipe. ‘Get up the yard, Desmond, and get out of the way till we clear out this stuff,’ we would reply, and he would smile and take to his rummaging afresh.

There was something deeply disquieting about Desmond Fennell and his smile and his pipe. What he was saying all along was that the reconstruction we were embarked upon was not necessarily well advised, not definitively justified, not unambiguously valorous or self-evidently correct. There were many others who said similar things, but virtually all of these others did not count by virtue of defect of intellect, fanaticism of heart or redness of neck. Such people bore only too obvious witness to their own error. But Fennell was different. He was, it seemed, quite an intelligent man. He did not speak like a redneck. He came, it was rumoured, from Belfast, and he had been to university in both Dublin and Bonn. He had traveled widely and had lived for extended periods in Spain, Germany, Sweden and the United States. He also appeared to lack all outward appearances of fanaticism. He spoke calmly, in structured sentences; he rarely lost his cool; and always there was the smile, as though he found the whole discussion faintly amusing but had nothing better to do at the moment than to join in.

Desmond Fennell’s books, too, posed a grave difficulty. Usually, if a reactionary has written a book, it is merely a matter of obtaining a copy and using the contents to taunt or dismiss him. The problem with Desmond Fennell’s books was that, once you had dug one of them out and perused it, you were left with the unsettling possibility that here was a man who, if he was right about anything might be right about everything. The only thing to be done, therefore, was hide the book away, present a false account of its contents and confine your analysis of Desmond Fennell to a satirical impersonation of him smoking his pipe.

The problem with Desmond Fennell, then, is not simply that he is wrong, but that he just does not appreciate how wrong he is. But there is an entirely different problem with Desmond Fennell’s thinking: Such is its complex inter-working and scrupulous attention to logic and progression, that, in order to ensure he does not turn out to be right about anything, never mind everything, it is quite obvious that things he writes have to be altered in the interests of the common good. Only by doing so can we protect ourselves from the appalling vista that he might one day turn out to have been correct when everyone else was saying the direct opposite.

Desmond Fennell himself has always seemed oddly prepared to countenance the possibility that he was wrong, if not about everything then perhaps about any thing or anything. In one of the articles reprinted in Nice People and Rednecks, he wrote: ‘I am in the business of thinking about things and making my thoughts public. There may be some people who pursue this way of life, and who believe that by thinking seriously and carefully they can arrive at the full truth about something, and state that truth in a manner which makes its trueness self-evident to intelligent people. If there are such persons, I am not one of them. I am a prober and a trier. I believe that, by thinking seriously and carefully about some matter, I can arrive at something like the truth about it — a first version of the truth, a trial version — and that there is a fair chance that this will seem true, or partly true, to some people. To progress beyond that, to get a better hold of the truth, to fill out my statement of it, and to make that statement more obviously true to some people, I need to place it in front of people and get their responses to it.’

Now this kind of thing was deeply inconvenient. For Desmond Fennell to fit into his allocated slot in the public discourse, it was imperative that his statements and behaviour follow a particular pattern. As someone who was — as clearly he was — resistant to some modern ideas, it was imperative, for example, that he be intolerant, inflexible, dogmatic and entrenched in his views. That we appeared not to be these things, but on the contrary open and flexible and anxious to hear other viewpoints, was deeply disturbing. It was, after all, a central belief in the manifesto of the modernising tendency to which many of us had sworn allegiance that everyone opposed to it was gripped by a profound intolerance based on ignorance and fear of losing power. Desmond Fennell, puffing on his pipe and saying, ‘Let’s have a good chinwag about all this’, was not behaving within his prescribed function. Moreover, the difficulty about responding to his invitation to talk was that he appeared to know what he was talking about, and was therefore in serious danger of winning the argument.

In some circles, this penny took a while to drop. There was a time, for example, when Desmond Fennel appeared regularly on Irish television. Then, one day, he ceased to do so. Observing him on and off during the years when he was a regular participant in debates on both television and radio, I was struck by the dissonance between what was clearly his allocated role in these debates and his actual execution of that role.

What is often not understood about media debate concerning social and political issues in Ireland is that things are rarely as they seem. On the surface, debates about nationalism, abortion, unmarried mothers or whatever, appear to be authentic confrontations between opposing opinions, with the media operators as neutral conduits and facilitators. In fact, these discussions are mostly staged debates between those who are ‘clearly right’ and those who are ‘manifestly wrong’. The purpose is not to ventilate an issue so as to enable the public to make up its mind, but rather to dramatise the confrontation between truth and error so that the public will become even more convinced of the truth. To this end, it is vital that those participating in public debate to defend what is ‘manifestly wrong’ must enter into a tacit agreement with their media hosts. This agreement incorporates a number of unstated but implicit conditions, viz.: Thou shalt defend the indefensible (for example, clerical child abuse) by dint of dissembling or prevarication; thou shalt wear strange, old-fashioned clothing, whereby to signal an out-of-touchness with modern society; thou shalt become incoherent with rage in the course of the programme; and so forth.

In media terms, Fennell was what is thought of as an ‘intelligent reactionary’, which is to say that media operators immediately thought of his name when seeking to stage a debate between liberals and conservatives, modernisers and reactionaries. Since he clearly disagreed with or could puncture much of what liberals said, it followed that he sought to do so out of the only possible motivation for such dissent, which were, broadly, to do with a desire to prevent the forward march of Irish society and return us to the dark ages. The problem with Fennell was that, although agreeing to participate in such debates, he refused to behave in the prescribed manner. His dress was unexceptional. He did not wear tweed jackets or ostentatious emblems associated with derelict or outmoded belief systems. Worse, he insisted on seeking to shift the argument away from the tug-of-war between alleged liberalism and alleged conservatism and introduced alternative ways of seeing things. Occasionally, he would cause absolute consternation by agreeing with the liberal voices (this was especially dangerous when it occurred on the national broadcasting network, RTE, which had a statutory obligation to provide ‘balance’ in debates, an obligation clearly breached when a panel suddenly appeared to be unanimous on a particular subject).

I once asked Desmond Fennell why he no longer appeared on certain radio and television programmes and he told me that he himself had decided to absent himself as he had grown tired of being used as a whipping-boy to enable liberals to demonstrate their correctness. I believe he is wrong about this, too. Although he may, in fact, have turned down one or two invitations directly, it was his behaviour when participating, rather than his refusal to participate, that made his continued appearances untenable. It was only a matter of time before they stopped asking him anyway.

I don’t want this to be misunderstood, or taken for ill will, but if I were Desmond Fennell, I might now have serious concerns about my prospect for earthly longevity. If it is true — and there is fairly widespread evidence to say that it is — that thinkers and artists are given enough time on this Earth to say what they have usefully to say, to complete, as it were, a coherent life-statement, and then move on, then Desmond Fennell may now, unless he has other errors up his sleeve, have completed his life’s work.

His most recent book, The Postwestern Condition: Between Chaos and Civilisation, is, by any standards, an enviable legacy to bequeath at what may or may not prove to be the end of a long career in public thought. Reading through his earlier work — Nice People and Rednecks, his collection of short essays written mainly for The Sunday Press; his longer pieces, published in Heresy; or his critique of nationalism, Beyond Nationalism: The Struggle Against Provinciality in the Modern World — there is a strong sense of a search for coherence in the modern melee. In The Postwestern Condition, there is an overwhelming sense of discovery, of searching for among most of — perhaps all — the elements with which his life’s work has grappled, albeit on the basis that there is no sense any longer to be found and that, moreover, this senselessness is the designed and required end of a process of civilisation which has unshackled itself from history, morality and restraint.

In The Postwesterm Condition, Desmond Fennell argues that western civilisation, as we have always understood it, has ceased, without us knowing, to exist. All of the values, principles, rules of behaviour, which have underpinned western art, politics, jurisprudence and morality, have been rendered obsolete, and been replaced by a different set of values, principles, rules and morals which owe nothing to coherence and everything to the rationalisation of what we term progress. This process, he argues, is enabled by the expansion of the money supply and the rolling affluence of western societies. He claims that the origins of this change are to be found in the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War Two, an action which so contravened existing western morality that it invited one of two responses: unequivocal condemnation throughout western society at such a deviation from what was previously thought right; or the deconstruction of those norms to make these events acceptable. Without anybody ever declaring this explicitly, the latter course was adopted. The tacit endorsement of Hiroshima, in its acceptance of the savagery of the indiscriminate massacre of civilians, women and children, therefore, had legitimated the illegitimate, and in doing so amounted to the rejection of western civilisation and the initiation of a completely new civilisation, as yet inchoate but struggling to find its feet among the debris of the old. Thus, by Fennell’s analysis, the influence of America in the modern world has brought to bear a completely new form of morality on world affairs, a morality by which certain things are justifiable even if they seem to be in conflict with previously accepted values and truths. Out of this, he argues, has developed a sprawling senselessness, which has spread to virtually every area of public thought in the societies over which American values have influence. He calls this place ‘Amerope’. It is not yet, he says, a civilisation, but it certainly aspires to being one. He calls it ‘a civilisation in the making’.

His thought-train takes him on an odyssey through the life of what we call the modern world, embracing gender politics, language, sexual liberation, media, masturbation, accommodation advertising, sitting down and much, much, much more. He strips the senselessness down to its chassis and looks at its naked nonsense. It is, though in other ways a deeply frightening book, in this sense reassuring for those who have been aware of this senselessness and imagined that they were simply going mad.

Out of this, Fennell fashions what, if it were to be his final contribution to the intellectual life of this planet, would be a sublime and clear-sighted statement of how he found us. I harp upon my sense of its possible finality, not because I believe its author to be incapable of further achievement, still less poised with one foot over the grave, but because, having read The Postwestern Condition, I am unable to imagine what Desmond Fennell has left himself to say. He follows the logic of his argument along its natural and inexorable course, observing as he goes. Fennell is not just an academic or a reporter, but an artist who writes the history of everyday society as it unfolds before his eyes, and not as a catalogue of facts but an illumination of meaning.

The Postwestern Condition is a taut, spare book, the text of which runs to just 115 pages. It is, in fact, a rewrite of a significantly longer book, Uncertain Dawn: Hiroshima and the Beginning of Postwestern Civilisation, published a couple of years before, which Fennell revised because he felt it had not correctly identified the incomplete nature of the emerging civilisation. The precursor was written as a diary, compiled over a few months around his observations on an extended holiday in the United States in 1994, and the later book is a distillation of the most essential elements of those diaries, with a new set of conclusions.

The Postwestern Condition is not an easy book to read. It presumes a great deal of the knowledge, interest, zeal and curiosity of the reader. Almost every second sentence is both loaded and laden with layers of meaning. It has about it that density and precision one associates with a George Steiner or a Camille Paglia, both of whom receive more than routine mentions in Fennell’s work.

The Postwestern Condition can be read in isolation, but with the greatest difficulty. Ideally, it should be read as a postscript to the previous works of Desmond Fennell, a final summing-up for the benefit of a jury which has been paying close attention but which now requires to be told what the evidence means. If, in his previous works, Fennell has adduced evidence, from his own society and those he has visited throughout his long career as an academic and writer, in this he draws it together in terms of its significance for the entirety of mankind. Here, we see him finally tie together the strands of enquiry he had been observed to untangle in Heresies and Nice People and Rednecks. In the last chapter in the latter book, he had framed, by way of summarising his own puzzlement with what he had been observing, this question: ‘...it is a matter of looking at this modern life as it is exemplified in Ireland, and of asking, in one domain after another: is that a fit life for a man, a pro-human or anti-human arrangement, or the most intelligent way of organising things?’

(I am interested in Fennell’s use of the word ‘man’. Fennell is the kind of man who always uses the word ‘man’, when he means not just men but women as well. it is a tendency which leads his work to be revised in the early hours by sub-editors anxious to protect their newspaper, reading public and not least the author himself from the consequences of such flagrant error. He does it, I think, not because he is a pedant, although he is probably that as well, but because he knows that sounding like a pedant will aggravate certain people enough to think about him and what he is saying. I am interested in it, too, because of a growing awareness in me that Desmond Fennell’s core theme is really the collapse of authority of the old kind, and its replacement with a form of authority which is untenable because it is founded on lies. Fennell belongs to the old authority, of classical civilisation, of what is termed patriarchal society, of western values based on Christian beliefs and teaching. And with his pipe in his mouth, this is precisely what he looks like, and precisely, too, why he gets up the noses of people to whom manliness is a red rag.)

What Desmond Fennell seemed to have in mind in that passage, and indeed in many of the pieces reproduced in that particular book, was something that had perplexed many is us in the latter part of the twentieth century: the development of a society in Ireland according to ideas with which Fennell had grappled all his life, ideas which did not appear to be coherent, but which emerged according to the exigencies of the moment and continued to remain long after they became untenable. When we wished to speak of the origins of these ideas, or the architects of the emerging society, we spoke of ‘liberalism’ or ‘pseudo-liberalism’, and ‘liberals’, ‘secular-liberals’ and ‘Dublin 4 liberals’. Fennell, like others, had sought for many years to dig up the roots of these phenomena, to establish the precise nature of their core motivations and aspirations, but without more than modest success. Like many of us, he had been assuming that there must be some sense to all this, a coherence too complex or too sophisticated to be perceived by those who most found it worrisome. Now, in The Postwestern Condition, Fennell has at last traced the root to its point of origin, and discovered that there is nothing there but the black hole of amorality represented by Hiroshima. It is a bold and spectacular theory and it makes sense.

This is not a book about Ireland, or Russia, or America, or Germany, but about all of those places, and everywhere else as well. There are just four pages in the book that relate specifically to Ireland, and these to the removal of explicit references to God and Christianity from the Irish Constitution and other key documents relating to the belief systems of Irish society. This section, as though included to demonstrate that Ireland is no more and no less than another outpost of the creeping post-western condition, provides a clue to the nature of Fennell’s voyage from the start. One of the accusations levelled against him was that he was a parochialist, a reactionary nostalgic, yearning for and seeking to recreate the conditions of Ireland past. Nobody who read his books could possibly say this about him, but one does not expect one’s critics to read one’s books.

When someone like Desmond Fennel sticks his head up in modern Ireland, and keeps it there in the face of the Aunt Sally masquerading as an intellectual debate, it is imperative that the general public be precluded from perceiving that there might be anything sensible in what he says. There are many devices for achieving this, including distortion, personal invective, demonisation and censorship. The Postwestern Condition has not been widely read in Ireland, and this is for a range of reasons, some of which are undoubtedly to do with the dense and difficult nature of the thought. But without doubt also, the fact that many people who might have profited from reading this book have not done so, has to do with a concerted effort to close Fennell down, to depict him in an unfavourable, antiquated light. Few of the devices used to achieve this have been as blatant as the manner of the critical reviewing of The Postwestern Condition.

The Irish Times, for example, published a review of this book by a Bill McSweeney, described as a teacher in the International Peace Studies programme of the Irish School of Ecumenics, which succeeded in avoiding any mention of the book’s main theme. The bombing of Hiroshima is such a clear-cut theme of this book that, in advance of actually reading it, one’s thoughts tend to drift as follows: ‘What on Earth is Fennell on about now, and what can the events at Hiroshima, more than half-a-century ago, possibly have to do with it?’ In other words, it is scarcely possible to pick up this book, flick through it casually and cast an eye over its blurb and Preface without comprehending that it is a book with the idea of Hiroshima at its centre, and to be sufficiently puzzled about this to investigate the logic of it. And yet, Bill McSweeney, writing in Ireland’s leading quality newspaper, did not, in the course of an 800-word review, use the word ‘Hiroshima’ at all. He described Fennell as ‘a fiery critic of modernism’; ‘a serial contributor to the Letters page’; ‘a staunch, if not always lucid defender of his own personal take on the human condition’; ‘an intellectual best described as a pamphleteer of the old school’; ‘a moralist who inveighs against contemporary ills’; and in sundry other ways. McSweeney characterised The Postwestern Condition as a torrent of invective against moral chaos (as though there might be something wrong with this if it were true) and accused Fennell of offering ‘little more than a litany of generalisations unsupported by any convincing evidence’. But at no time in his review did the reviewer either tell his readers what Fennell’s book was actually about, or suggest that he was even aware of what the core subject was. There are, it seems to me, just two possible conclusions: either the reviewer did not read the book at all, or he wished to withhold from his readers the most basic intelligence concerning Fennell’s actual subject matter. If this was his intention, he succeeded admirably, presenting this latest book by Desmond Fennell as ‘yet another’ tiresome rant about the terrible nature of modern life. One is struck by the thought that, if such people were really as convinced that Fennell is as wrong about everything as they would have us believe, they might at least outline fully the extent of his error, so that we could all have a good old belly laugh at his stupidity.

It is strange that Desmond Fennell’s work appears to attract, in the most acute way, the full brunt of the conditions which he diagnoses. When he talks about the split that occurred in the western mind following Hiroshima, he is describing a kind of global dissociation, a severing of logic from emotion to as to justify the monstrous, something close to what T.S. Eliot called the ‘dissociation of sensibility’ in the modern condition. It is interesting to observe that the very disease which Fennell diagnosed is capable of producing unlimited amounts of the intellectual microbes required to keep the virus of sense at bay. The targets include, unsurprisingly, both Fennell and his analysis.

I recall watching a television debate in Ireland at the time of the publication of Uncertain Dawn, in which Desmond Fennell was pitted against an academic from one of the Dublin universities. Fennell was at a disadvantage in that the presenter, typically, had not read his book, but he was making reasonable headway in explaining himself and his ideas when, out of the blue, someone said something about unmarried mothers and the epidemic of fatherlessness in the United States. Fennell elaborated on this crisis for a moment or two, outlining some of the social damage that resulted, particularly as it related to fatherless children. Then, with an almost audible gulp, the academic launched into a retort centred on the fact that his own father had died when he was a small child. ‘Does that make me a leper?’ he demanded. ‘Am I a leper?’ He was visibly shaking and almost dancing with rage. At this moment, Uncertain Dawn died an instant death in the public mind, a book so full of error that it had nearly made a grown-up orphan cry. The audience immediately rushed — all but literally — to the side of the bereaved academic. Desmond Fennell was dead in the water, the man who had tried to suggest a poor innocent child, deprived of his father at an early age, was some sort of leper. There are, of course, ways of answering this kind of emotive nonsense: It is possible to make a very clear distinction, for example, between children who lose a parent by death and children who are deprived of a parent though the unexplained disappearance of that parent, or worse, the sense that the parent has voluntarily abandoned his child or children. Fennell did not seem minded to resort to such argument. He was probably right, for there is no place for logic in a cauldron of piety and emotion. Such is the nature of intellectual debate in modern Ireland.

Ireland has essentially three kinds of writers: one, those who focus on the local to the exclusion of everything else; two, those who focus, for precisely the converse reasons, on everything else to the exclusion of the local; and those who seek in Irish life and society an illustration of the universal, both to illuminate the local and better comprehend the universal. In this final category, Desmond Fennell is perhaps alone among his contemporaries.

He is great indeed. What sets him apart is that he set out willing to be wrong, to cast his eye over Irish society and try to make sense of it, not of itself, but of its place in a greater order. And what he has discovered, finally, is not its place in a greater order but in perhaps the greatest disorder the planet has ever seen.

No. Desmond Fennell is not a reactionary, nor a nostalgic, still less a parochialist. No, and as he says, he is against fixed ideas; he wants us to think long and hard about where it is we want to go, the better to get there in good shape and remain there in safety. If he harps upon the past it is not that he desires to return there, but that he demands of those leading us elsewhere that they say where it is they propose to take us, and how they think we are going to live when we arrive. Desmond Fennell, far from wishing to remain, merely wants to be reassured so that he can be first upon the bus on the morning of departure, smoking his pipe and smiling at the latecomers before leading them astray with the error of his ways.