Bonus Content: Diary of a Dissenter: Week One of an Ominous Year

In the first, telling, week of an ominous year, I describe the origins and coming peril of our situation, and, not randomly, the funeral of the greatest spiritual leader Western civilisation has had.

The Lord has called him to Himself

SUNDAY

I remember the first day of January, 1973 as though it were last Monday. I was 17, studying (or, mostly, not) for my Leaving Cert, which I was to sit the following June. Over the Christmas holidays, as was my practice, I travelled with my father on his ‘stagecoach’ runs, helping with the mailbags and newspapers, emptying the pillar boxes, acting as door-opener for passengers, and generally riding shotgun. Normally, the mailcar was a clamour of argument, disagreement, insults, laughter and the occasional shouted ‘Yahoo!’ This day it was different — funereal, mainly in deference to my father’s mood, which was uncharacteristically morose. ‘This’, I heard him say to passenger after passenger, ‘is one of the worst days in Irish history!’ The decision to join the ‘European Common Market’, voted on by the Irish people the previous May, and carried by a landslide of 83 per cent to 17, with a turnout of 70 per cent, came into effect that day. My father, who had been one of 211,891 Irish people to vote against joining, believed membership would lead to the destruction of the Irish farming and fishing industries, and make us the paupers of Europe. He insisted that the required trade-offs — especially the exchange of sovereignty and natural resources for infrastructure and subsidies — would erode our longterm capacity for self-sufficiency, bringing with it renewed dependency, deceptively easy money, increasing debt and a degeneration of our political class. He was right on every score. If he were alive today, he would take no pleasure in his ‘vindication’, even though the evidence is to be seen all around.

The argument against Ireland’s membership was especially unpopular during the 1980s and early 1990s, when large amounts of structural and cohesion funding became available and Ireland was a net beneficiary of community largesse. In 1972, and even in the years immediately after we joined, we had hopes of developing an indigenous self-sufficiency, while using our membership of the European Community in ways that might eventually have supported an independent nation and culture. On paper, the Irish population should be capable of sustaining itself without difficulty on what is available to it. But nobody in Irish politics was offered a coherent vision concerning how this might be pursued. Whenever Irish objectives were at odds with the drift of the community, we chose to accept monetary compensation rather than insisting on retaining certain essential capacities and resources within our control.

For most of the century since achieving nominal independence from England, Ireland had struggled to survive and to maintain its population. In the 1930s, and again in the 1950s, we suffered enormous haemorrhaging of our people, a pattern that had persisted since the Great Famines of the 1840s. There was a brief respite in the 1970s, arising from a momentary optimism created by a new kind of leadership — leading people to imagine that we had made a wise move in joining what was then the EEC — but emigration resumed again in the 1980s and persisted until the ‘miraculous’ boom of the 1990s.

Today, Irish agriculture comprises mainly beef and dairy farming, by far the least efficient use of land. If you drive around the fabled countryside of Ireland, you cannot avoid noticing that almost none of the land is cultivated, and this is a symbol also of other oversights and neglects. Our fisheries are mainly exploited by Spanish fishermen because this was part of the firesale that enabled us to construct the vestige of a ‘modern’ society we have now. Our tourism industry is in the doldrums because we cannot decide which version of ourselves — traditionalist kitsch, or cutting-edge modernity, or tax haven — we wish to promote.

The two brief periods of resurgence of the Irish economy in the 1970s and 1990s were based mainly on two phenomena — budget deficiting (i.e. borrowing) and invited dependency. Today, we are per capita one of the most indebted nations in the world. The economic model pursued by latter-day politicians has been one which abandoned development of indigenous resources in favour of doing deals with the outside world. Ireland gave itself the lowest corporation tax rate in the world, so as to attract multinational operators with a view to attracting employment, thus obviating the necessity for deeper thinking. Our fishing rights were traded as part of our European Union membership, in return for structural funds to build roads. Nobody in our political class today offers any vision by which Ireland might proceed outside the EU or in a reduced role within it. Our leaders know no other way of running our country except in some kind of dependent relationship with some larger entity.

It is a cliché of Irish politics that ‘we are all Europeans now’, but any close observer of the discussion since it began would have to conclude that nobody had any real interest in anything except the structural and cohesion funding. The founders of the 'European project’ — Monnet, De Gasperi, Adenauer, Schuman — are almost unheard of in Ireland. Very few Irish people would be able to mount a convincing argument concerning the cultural and spiritual characteristics of Ireland’s place in that ‘project’. Unsurprisingly, given that the project was sold for three decades as an opportunity to obtain financial hand-outs, voters remained cynical about any attempts at describing a deeper connection.

I was for many years deeply suspicious of the European project, mainly because of its bureaucratic dimension and the way it treated democratic endorsement by way of a rubber-stamp on decisions already taken by politicians and officials. I had strenuously opposed the Maastricht Treaty in the referendum of 1992, which was really the moment of no-return for Ireland as a going concern on its own steam, at least under the guidance of the kinds of politicians we had started to throw up. With that treaty, the EU ceased to be merely a cooperative community, acquiring many of the characteristics of a single political entity. I had assumed that, in voting Yes to Maastricht, the Irish electorate was aware of the choice it was making. It seemed obvious that the argument for an independent, self-sufficient Ireland was lost. Ireland had become so dependent on the relationship with the community that, henceforth, almost everything that concerned our future would have to be pursued from an acceptance of this dependence. I remember well the condescension and hostility of the political and media establishments back then, as we sought to persuade people that voting Yes to Maastricht would be the most disastrous decision we would ever make. Later, I argued against European Monetary Union and the introduction of the Euro, but was on the losing side of these arguments also. These developments resulted in the Celtic Tiger, a materialist carnival that lasted for ten years, and which the Irish people in general embraced as though it were the arrival of the Promised Land, the outright vindication of the choices they had made. I politely continued to point out that this was delusional, that the prosperity we were enjoying lacked a solid basis. But, in the face of what appeared to be the facts, I eventually stopped talking. Today, I must record that everything my father warned about has now come to pass.

For nearly 50 years, the idea of Ireland as a nation-state has been subjected to the cultural equivalent of carpet bombing — every hour of every day, from every newspapers and broadcasting station. The Irish people have been subjected to relentless propaganda concerning the merits, the inevitability and singular correctness of the EU project, and the invalidity and indeed moral questionableness of the national idea. This has penetrated every remaining crevice of public thinking, although these are now few and far between. At the time of the Maastricht referendum, I used to ask people why it was that the unity and self-realisation of a larger entity like the European Union was to be regarded as ipso facto good, whereas the self-realisation of a smaller entity, like Ireland, was to be regarded as dangerous and wrong. Nobody could coherently answer this question except with the old justifications for European integration: to prevent a recurrence of the world wars of the 20th century. So, the reason we acquiesced in the beggaring of our children’s children is to discourage the Germans from reducing Europe to rubble for a third time.

Europe is a continent rich in culture and history, the centre of the Christian civilisation that transformed the world. The EU is a bureaucracy, which treats culture as something irrelevant and non-essential, soul as some residual anachronism, and faith as something to be 'tolerated' rather than embraced. In the absence of a cultural and spiritual vision, the economy has become at once everything and, inevitably, a nothing.

This failure of the EU project to capture the imaginations of its people is not merely 'coincidental' with the retreat from Europe's rich Christian heritage. There is a causal relationship between the two. The retreat from an understanding of first causes — once loudly and proudly expressed in the Christian narrative and transmitted via the richest culture the world has known — has left a vacuum which economics, liberalism and materialism has unsurprisingly failed to fill.

For various reasons, what evolved into the EU was never articulate about itself in cultural terms, but instead resorted to a language and logic of materialism and secular democracy. Its drivers made the mistake of thinking that a society can form itself willy nilly out of a melting pot of ethnicities and cultures. Instead, what happens in such experiments is that, without a strong and assertive host culture at the centre, the multicultural mishmash lacks any context for unity, and so divides into a multiplicity of enclave entities. This process can be seen in many European countries — in Holland, France, Sweden, the UK, where immigrant populations, attracted by prosperity and modernity, converge for economic reasons only, and end up weakening rather than strengthening the host cultures they seek to live off. In the same way, all of the member countries of the EU are as immigrants to the idea of European Union. They came to it in hope and expectation, but having got there have found the core vacated, a hole in the doughnut of the unity they anticipated. Thus, fundamentally, the EU and Europe have no prospect of ever being coterminous entities.

MONDAY

I caught a headline a few days back, on some American website, that took me to worrying: ‘Zelenskyy, BlackRock CEO Fink agree to coordinate Ukraine investment’. The report expanded that Ukrainian president, Zelensky, and BlackRock CEO, Larry Fink, had agreed to ‘focus in the near term on coordinating the efforts of all potential investors and participants in the reconstruction of our country, channelling investment into the most relevant and impactful sectors of the Ukrainian economy.’ I hear that the ‘wags’ on Twitter are saying that this means that BlackRock now ‘owns’ Ukraine, which I suspect they intend as a joke. It is not a joke. BlackRock ‘owns’ everything — ‘. . . most likely including Ireland!’, (he joshed, but that is not a joke either). This, in fact, is the deep meaning of the ‘Covid project’ (Ⓒ World Bank) which flowed directly from an all-points bulletin issued by BlackRock on August 15th 2019, warning that extreme interventions would be required for the next downturn, the pistol-shot that unleashed the ‘pandemic’. The plan that was rolled out had been hatched back in 2013, by the Obama administration, and essentially couched as a wartime response. The vaccine was treated as a ‘counter-measure’ — i.e. a military response, with all laws concerning vaccination testing suspended. In Ireland, I understand, a top-level meeting involving politicians, judges and other key figures, took place in December 2019, at which it was agreed to suspend the Constitution, itself an unlawful action based on no authority whatsoever.

De Covid changed everything: demolishing rights and freedoms, corrupting democratic conversations, abolishing parliamentary democracy and national sovereignty, and creating an entirely new understanding — and therefore an entirely new dispensation — of law and public administration. Henceforth, it was to be taken for granted that what had previously been rights and freedoms were now concessions of power, and any form of declared ‘emergency’ meant that these concessions could be instantly revoked. It also, noiselessly, put an end to an understanding that almost nobody has ever given any thought to: That there is a legal as well as a moral buffer between public debt and private debt. This understanding had been rattled — or, should I say ‘tested’? — before: in 2013, when a one-off levy of close to 50 per cent was imposed by what we called ‘the Troika’ — the EC, the ECB and the IMF — on depositors with the two Cypriot banks, applied to all funds over €100,00. The proffered reason was that Cyprus had become a ‘tax haven’ — mostly for Russian money — so the ‘bail-in’ was a precondition of a national bailout package.

There was, of course, uproar, and a degree of rolling-back occurred; but, by more than one account, there are still people living in tents in the parks of Nicosia on foot of the losses they incurred in that episode.

This, it was pretty clear, was a try-on, with a view to establishing a precedent, so as to dismantle all prevailing understandings of the relationship between money and the citizen. No longer could there be any presumption of the citizen concerning the ownership of what he hitherto presumed to be his personal assets.

About a dozen years ago, in the wake of the Troika’s visitation to Ireland, I began writing about the nature of money in the modern economy, and the contemporary world — in particular about the nature and functions of debt and how remote is the reality of this phenomena from the common understanding of it. It struck me at the time that, despite the acres of newsprint contaminated by journalistic and economists analyses of the fallout from the 2008 economic meltdown, nobody — and I mean nobody at all — was writing or talking about the relationship between money and debt. Although this was the heyday of the economic ‘expert’ preaching doom and gloom, such questions were rarely if ever raised, for the obvious reason that most of these ‘experts’ worked for banks, which did not want such questions ventilated. I noticed this strange characteristic of the debate that, although seeming to cover all the potential ground, it always remained within orthodoxies until these had become utterly hollowed out by the attrition of reality. Nothing cut to the deeper moral reality, beneath the propaganda and bullying of the establishment and its puppets. Only on alternative platforms were we able to eavesdrop on fundamental discussions about the role and function of money in human society, and the extent to which this had become corrupted by interests who had fetishised the tokens of human exchange to enrich themselves and their accomplices.

Money, fundamentally understood, is a technology for releasing energies, establishing value and keeping score of the contributions and entitlements of economic participants, enabling the citizen to trade his labour or belongings in a convenient and uncomplicated manner. In the undertows of virtually every conversation about money conducted nowadays is an entirely different idea: that money is possessed of intrinsic worth, with the capacity to become ‘scarce’. Of course, scarcity is an essential characteristic of money — that being what enables it to hold value — but this scarcity is supposed to track the relative scarcity of, and the difficulty in acquiring, real wealth. Money is not a real asset, but simply a way of providing convenient tokens for real assets. Money ought be ‘scarce’ only as a reflection of the availability of the quantities it is used to exchange, not as an instrument of manipulation. A coin or currency note asserts a claim on real resources, such as goods, services or property. Banks are permitted to generate these tokens of wealth in the form of credit, allegedly based on confidence in the ability of economic actors to create the real thing, in the form of work, services, houses, roads, businesses, infrastructure et cetera.

Modern central banking amounts to a form of priestcraft, whereby the process of ex nihilo desubstantiation is employed in the manner of a three-card trick trap to ‘liberate’ the owners of real wealth from their property and assets. As with the fairground hucksters, the bankers engage in a constant shifting of the tokens of exchange, enabling their marks to feel liberated into a form of pseudo-wealth, in which they are able to buy things of minor value and pay off the cost, or things of major value and acquire a massive burden of debt — which in turn generates a new category of tokens in the form of, for example, bonds, which end up in the possession of very wealthy and powerful interests who, when in due course a crash is unleashed, end up with a ‘legitimate’ claim on the actual wealth represented by the tokens — mostly land, property and businesses. At first sight, this process might be termed ‘ex nihilo transubstantiation’, but this may be misleading. Whereas it is true that it appears to allow money to be generated ‘out of nothing’, it would be more accurate to say that it allows assets to be dissolved into nothing and later reconstituted under new ownership. Using a completely non-existent money, the conjurers give themselves the power to dissolve, over time, real assets — true wealth, as opposed to paper wealth — into a plunderable state and render it transferable to themselves and/or their friends. This is what we mean by ‘fiat money’. It is really just another word for ‘theft’, since it enables those who are able to manipulate the economic forces and financial conditions to their advantage to work loose the assets of those who are not, and eventually release these assets into their own keeping. To make this process appear respectable/ethical, they also require to make it seem— to the notional ‘objective’ observer — that the party being defrauded has been reckless, has ‘lived beyond his means’. Since in the vast majority of individual instances, this is not true — people have merely sought to secure the wherewithal to rear their families and have a decent life. The only instances where that charge may have some truth is in respect of the Davos billionaire manipulators, who are among those with the means to leverage the ex nihilo mechanism.

The art of financial priestcraft, or ex nihilo desubstantiation, then, is not, after all, an illusory process of mere token-generation: It serves ultimately to trade in real things, real property, while disguising this as mere symbol-creation, and calling it business. The three-card trick trap necessitates the fiat money system being used to target, secure, dissolve, divert and eventually plunder real assets from the people who have, in most cases, built these up from nothing, often with their bare hands. Gradually, imperceptibly, over the past few decades, the trick has been used to siphon off the real wealth of enormous numbers of people, who are temporarily reduced to impecuniousness by forces over which they have no control, and transfer it via the banking system into the pocketbooks of the ‘elite’. Most of the tricksters are represented by BlackRock — or, if not, by agencies that are, for all practical purposes, subsidiaries of BlackRock, an organisation with the capacity to buy politicians, editors, judges, scientists and intellectuals with what for them is chump change. They are also rumoured to have the capacity to buy disappearances and accidents, of which more than a few have occurred in the course of the Covid Project.

This situation is a function of an unannounced, gradually-imposed alteration in the nature of economies that has crept into — especially — Western societies over the past few decades. In that time, the ‘traditional’ labour-based economy has constricted to the point of obliteration, and a new form of economy exploded into existence which is entirely about ‘money’ — i.e. the ‘commodity’ being the tokens of exchange as opposed to the substances or entities being traded — and the tricks bankers and stock-jobbers can pull to make it grow without any reference to the concrete world. Even though this economy has been expanding for over 30 years, and now accounts for the vast majority of financial transactions, the public conversation continues to speak of economics as a ‘science’ of commerce and trading, as if nothing at all has occurred. Economists talk about growth and GDP, as though these were still the measures of something significant and beneficial, whereas they are really no more than the equivalent of a bookie’s odds. In this new and almost entirely spurious economy, real human activity is no longer regarded as relevant, because it is not. The powerful interests are no longer the representatives of labour and high street business, but of the major banking groups and investment brokers. The citizens of the ‘real economy’ are mere cannon fodder for these processes of ex nihilo desubstantiation — manipulated and punished in predictable succession, one minute showered with ‘gifts’ of ‘cheap’ money, the next subject to a false lack suggesting that something fundamental and vital has disappeared from the world, rather than simply from their bank accounts.

‘Our’ money system is owned and controlled by the banks. This is the way our leaders have decided things should be, and there has been no appreciable dissent. Privately owned banks, operating all but indifferently to the public good, create and destroy money more or less at will. Consequently, all but a tiny percentage of our money system exists in a digital limbo inaccessible by the people. For every euro of money created, a corresponding debt is brought into being, and this is multiplied over time by interest-levying. Thus, our economy consists overwhelmingly of debt.

What used to be ‘our’ money system is nowadays owned and controlled by privately-owned banks, which create Euro or Sterling or Dollars by a process that uses debt as the sole means of token-creation. Money is generated only when it is borrowed — each new loan means that a specific amount of money is brought into being. When the loan is eventually repaid, the capital is eliminated. Meanwhile, somewhat greater amounts of new debt materialise in the form of interest, which continues to exist as a negative phenomenon, without any positive corresponding element of wealth, or even tokens. The generalised accumulation of debts in the system, without any basis other than on the computer screens of the lenders, means that there is a diminishing pool of ‘money’ with which these mounting debts can be paid down. The interest exists nowhere except as a debit, and so the growing accumulation of debt in our economies is not a random misfortune, but a structural inevitability, which eventually results in the pauperisation of those whose access to the tokens is restricted by those holding the power. The continuing scramble to find money to pay down interest means that the only way debt repayments can be discharged is by borrowing more money, which throws the structural ‘flaw’ into a new and wider orbit.

‘Our’ money system generates debt as a direct function of this structural incoherence, in much the way a barber shop “produces” tufts of hair. But debt cannot be swept up and put in a wheelie bin, which is perhaps why ‘economists’ are forever talking about ‘haircuts’ and ‘hairshirts’. Through the manipulation of the process of boom-and-bust, the money-changers are able to liquidise real wealth in the form of property and businesses, and channel it upwards to further enrich the already obscenely wealthy. This process, ironically, has accelerated in a period when, ostensibly, Western society in general was ‘moving to the left’, culminating in the ‘Covid project’, when, with the economies of the world on life-support, something in the region of four trillion American dollars were transferred upwards from small and medium-sized businesses to the wealthiest corporations on the planet.

Morally speaking, money is only ‘valourised’ into real value by socially useful enterprise and real labour subsequent to its creation but here a route is opened up whereby real wealth can be transferred by, in effect, a multiplicity of three card tricks. This desubstantiation is actually more spiritually audacious than even transubstantiation, and yet almost everyone is unconscious of it, and it is conducted without a hint of shame or apology on the part of the conjurers, who, of course, have the means to buy the silence of the ‘archdeacons’ of public conversations, otherwise known as economists and economic commentators. At the core of the occult (i.e.hidden) works of the system of modern western materialism is a portal to pure spirit, and from this portal the priestcraft of the bankers brings forth symbols of wealth-exchange and storage, allegedly on behalf of the people, but in reality in a profane manner that improperly enriches themselves and their clients, and impoverishes the many — ultimately transferring everything to the tiniest minority of wealth-hoarders. The collective failure of our society to educate itself about the nature of the financial, economic and banking systems — on which we have depended for the provision of our material needs — has brought us now to the brink of absolute disaster. As Jung said, modern man has lost his sense of the uncanny; a deficit that is now about to allow him to be stripped of everything.

This credit/debt creation system — which has remained for half a century hidden in plain sight at the centre of the banking system — is now poised to make its ultimate strike, and call in all its bets. Those end-of-the-line bond-holding interests are nowadays represented by BlackRock, the organisation that — remember! — triggered the Covid project and dictated its terms, and now seeks to persuade the governments of the West to deliver its greatest ever payday. This is the true, deep meaning of Davos, which is not, after all, just a club for egomaniacs, psychopaths and nonces.

There is a reason why politicians, who used to go around cap-in-hand looking for votes, now speak to the public with what looks like poorly restrained hatred, the sadism and viciousness bursting out through their fake grins. There is a reason why they promote senseless projects like transgenderism and Drag Queen Story Hour, and why they seek to flood their countries with indifferent and mostly uncivilised aliens, who create nothing but chaos. There is a reason, too, why they have started to mumble things about ‘bypassing the Constitution’ and not wanting to ‘force people’ to accommodate Ukrainians in their homes and properties, but y’know, compassion. There is a reason why, probably this year, Ireland will go to the polls on a question concerning whether or not the right to private property should remain sacrosanct. The reason for all this is that the politicians have received a number of further messages from BlackRock, in which their instructions for resolving the present debt-created crisis have been made abundantly clear.

The ‘solution’ our ‘elites’ have come up with is to privatise debt and make the property of everyone subject to seizure — initially in the name of ‘compassion’ for Ukrainians, but not really. This is the last hope the political elites of the West have of clinging to their cushy numbers, or even their lives. What is coming, it appears, is some kind of process whereby private assets will become, in the first instance, public property and public debt will be privatised. Then the property will be reallocated to those holding the chits. This is planned, on the instructions of BlackRock, as a way of conducting a controlled explosion of the present money system which is now on the point of blowing itself up. The purpose of the Covid project was multi-layered: To stand down what was left of the ‘real’ economy while they engineered into place a new system, Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC), to allow BlackRock and its clients to continue in the manner to which they have become accustomed.

Put it like this: Right now, the West is, economically speaking, a busted flush. The debts of every country far exceed any capacity or hope of their ever being repaid. As the money systems come down, the Euro, Dollar and Pound Sterling collapse into themselves, and the central banks prepare to roll out their CBDCs — replete with social credit schemes, blanket surveillance, universal basic income and a general condition indistinguishable from totalitarianism — it is vital, from the BlackRock perspective, that not a drop or crumb of their clients’ ‘wealth’ should go astray. If this means the impoverishment of the vast majority of the West’s population, then so be it, says BlackRock — not our problem.

What about democracy! Well, this was part of the purpose of the suspension of democracy in the Covid Project: to purge all those old-fashioned notions from Western heads, so that they might absorb and digest Larry Fink’s sage advice that democracy is not a good fit for the emerging forms of capitalism, and totalitarianism the only workable way forward. This has been the meaning of lockdown (a rehearsal for martial law); and mass vaccination (the launch of a new biometric system of controlling and sanctioning humans beings so they learn to do as they are told and not cheek their leaders; the Ukraine war (a pretext for dismantling most of the Western economy in accordance with BlackRocks’s demands); and the migration crisis — a ploy to destabilise the West by importing feral young men from the Third World, so as to be able to provoke civil strife and justify the introduction of martial law when the excrement hits the extractor fan, with a strong likelihood that many of the young men are trained UN military auxiliaries whose job will be to put manners on the natives should they seek to stir up bother about being robbed blind. This, in short, is the meaning of that great 2020 ‘conspiracy theory’, the Great Reset, and also the meaning of the current overnight obsession with the ‘climate crisis’ — just another scam to provide a gracing aspect to what is happening: ‘Saving the planet’ sounds better than ‘saving Jeff Bezos’!

‘Mortgage’ derives from an ancient French word meaning ‘dead hand’. The dead hand of BlackRock is now at the throat of the West, and in the other claw it holds all the cards. The cumulative debt of most countries now exceeds even their total nominal wealth, not excluding the buildings and land, every withered leaf of it, every blade of grass, every grain of sand. This is as a direct and predictable outcome of the processes described above. The three card-trick trap, applied with the aid of the manipulation of Western greed, delusion, and a form of induced social derangement, has ensured that all the major currencies of the West are grotesquely overvalued. The manipulation of ex nihilo ‘money’ has enabled the West in particular to construct the semblance of prosperity, but all the while the promissory notes were building up and accumulating in the pocket-books of the clients of BlackRock. These conditions have also, incidentally, provided the illusory space for the present craziness of the West to blossom and grow, a parasitical ideological derangement that is hastening the disintegration of both Europe and America as the chickens of its economic and financial inattention come home to roost.

To ‘justify’ the intermittent plundering of real resources and assets, the banking elites and their secret-unknown instructors, find it congenial to cloud the issue by manufacturing a fake degeneracy of the society more generally, so the charge appears to have a degree of plausibility. This, in addition to demoralising the natives with filth and nonsense, is the chief function of Woke in the plunder strategy. Even those who are being robbed — indeed, especially those who are being robbed — must be placed in a situation of being unable to rebut the accusation that access to easy self-enrichment has led the society (in this instance the West) down a path of debauchery and senselessness. The reason Woke has become an essentially mandatory agenda of change for Western societies is that it is a constructed programme of dissolution to be used to justify the plundering of Western assets on the familiar ground that ‘we all partied’. To a degree it is true, except that the dissolutes, more often than otherwise, are not the ones being robbed — indeed on closer examination you find that, through the leveraging of their envy and resentment, these are usually complicit in the process of looting those who own stuff. There is undoubtedly an increasing amount of parasitism and degeneracy in the West, but it is not indicative of the broader community, which is mainly hard-working, creative and energetic in pursuit of survival and innovation.

The narrative has it that, for half a century, the West in general has behaved like an individual who has won the Lotto and no longer needs to work. He swans around the place, dreaming up all kind of fantasies and debaucheries. He doesn’t know what to do with himself. Nor does he appear to notice or care that he is no longer even paying for his keep, living within his means, or contributing anything that is not destructive of the fabric of civilisation. He counts nothing but the money in his pocket and bank account, and this satisfies him not only that he is ‘successful’, but that it will always be so. But he is not successful in the least: The game has the appearance of being rigged in his favour so that he can appear to cheat reality, to beat gravity, but only in the short term. If he had at least the sense to realise that the whole thing was a three-card trick, there might have been some hope for him, but he took the bottom line at face value and forgot to look at the fine print that taketh away, until the sheriff came knocking on his door. The escalation of public and private debt has created an unsustainable bubble that now hangs over the West like a mirage of a mushroom cloud. Except that the cloud, unlike the money-tokens, is real, and deeply threatening to the future functioning — nay, the very survival — of the West.

Very soon, the people of the West will awaken to the realisation that their governments have, in effect, mortgaged everything, including their citizens’ homes and bank accounts, for their own political survival. This will mean that even someone who is debt-free and living within his means will be in the firing line when the boys from BlackRock arrive to take what’s ‘theirs’.

For many years, commentators and ‘experts’ in the West — including so-called ‘economists’ — had been declaring that we could continue to ‘print’ money without consequences — provided we could manage the interest payments. This is pretty much the same as arguing against gravity, and now the facts of reality are about to hit home. Due to the associated policy of ‘offshoring’, whereby many of the processes of actual production were farmed out to poorer countries, the West is essentially unproductive, collectively bringing almost nothing to the party apart from noise and nonsense, and has for some time disdained its own working class and elevated every kind of pervert and lowlife to the status of demigod. We have sub-contracted all our significant industrial processes and spent our days playing the international financial roulette table. Like the oak tree apparently standing proud in the forest, but secretly rotting behind its bark, the West will continue to prevail until, one day soon, BlackRock CEO, Larry Fink, will walk up and touch it with his little finger. The rest will be history. We will own nothing, and Larry Fink will be a happy man.

Had we decent and intelligent leaders, we might still be able to find a way of turning this juggernaut around without destroying everything that is meaningful about our civilisation and its systems, which self-evidently is the only moral course through this calamity. Since there is no moral basis to the financial system as it stands, there can be no moral basis to the claims of BlackRock and its clients. Some 36 years ago, in the midst of a much lesser crisis facing Ireland then (the national debt was at the time £27 billion, a mere bagatelle by today’s standards), I appeared on the Late Late Show with Gaybo, arguing for the repudiation of the national debt. Oddly enough, the arguments I met with were not moral ones, but pragmatic concerns about our being ‘unable to borrow anymore’ — precisely the root of the sick thinking that has brought us to our sorry pass. Things are now so bad that this argument has no traction, since further borrowing, even if possible, would simply dig us deeper into the hole. Repudiation is the only moral and practical recourse for the West.

Since we are not run by moral or intelligent beings, the ‘solution’ they have chosen, or agreed to, is the plundering of the resources of their peoples and their advice to us is to shut up and suck. In preparation, they have agreed to the full package of measures recommended by BlackRock/Davos, including the controlled demolition of Western industry, the removal of any residual constitutional protections for the old dispensation, and the introduction of ‘hate speech’ laws, designed to consolidate the mutism imposed on Western societies with the help of the LGBT goons, BLM and other agents provocateur who do the bidding of the Combine in return for payment and/or having their agendas fast-tracked by Western governments.

Hence, all the recent talk about a constitutional referendum in Ireland on ‘delimiting’ property rights, ‘bypassing the Constitution’ and ‘targeting holiday homes’. Varadkar and his slimy accomplices, of course, cite the ‘compassionate’ ground of housing half of Ukraine — in itself outrageous and criminal beyond description — but in reality their motives are, if this may be deemed possible, worse: They seek to dispossess Irish people of their hard-earned assets so as to compensate a bunch of bond-gamblers who have acquired a claim on them by virtue of the corrupted nature of the money system, in which the vast majority of Irish people has no beneficial stake and played no part in constructing. This is the endgame of their takedown of the democratic system, the reasons that Covid was invented — yes, I said invented— and the explanation for all the evils, cruelties and criminality we have witnessed over the past 27 months. This is the ‘Covid project’, the reason for the bioweapons, the lockdowns, the vaxxes, the Ukraine war and the attendant sanctions designed to bankrupt the West while pretending to be directed at Russia.

In effect, we are talking about the biggest bankruptcy suit in the history of the world. The economies of the world are kaput, especially those of the West, which have farther to fall. The receiver has been called in and has recommended a period of economic probation, to give time to allow a sense of the coming remedy to leak out and sink in — incrementally, so as to avoid a major shock of social outrage taking the wagon off the rails. The people need to be given time to adjust to and accept their new situation, to grieve their freedoms, wealth and property, to come to terms with their new situation: Outside it’s Beijing!

TUESDAY

Our heroic friend, Patrick Walsh, from Kilkenny has been stirring it up again, submitting a complaint to the Broadcasting Authority of Ireland (BAI) about the failure of his local radio station to report on the escalating mortality figures he has extracted from RIP.ie, as reported here over the past month. The response of the BAI’s Broadcasting Complaints Officer, James Gunning, breaks new ground in evasiveness, gaslighting and — it must be said — a certain ingenuity in framing a new understanding of the role and functions of a broadcasting regulator.

Mr Gunning writes:

‘[P]lease note that the broadcaster retains the editorial right to choose what they broadcast, providing they adhere to the BAI’s Codes and Rules. The BAI are only permitted to consider complaint referrals that are specifically about broadcast content and in this case, your complaint is based on omission. We have therefore invalidated this complaint.’

It would take me a lengthy article to, as the Americans say, ‘unpack’ Mr Gunning’s response, but I can for the moment say little to improve in Patrick Walsh’s paraphrasing of the BAI Catch 22 response: ‘You can only complain about something that has been broadcast, and the fact that they won’t broadcast it means you have nothing to complain about. . . . no one is accountable for not broadcasting about this life and death matter because no one will broadcast about it.’

In other words, what the BAI is suggesting is that there is no obligation on the part of a radio station, in its news and current affairs coverage, to report on what is actually going on in Ireland or the world. What matters — and we know this matters to the BAI, which has long had very strict rules about the proportion of broadcasting time to be devoted to news and current affairs — is that the stations have news bulletins and current affairs content, and beyond that it is no business of the BAI whether a station broadcasts actual news of what is happening in the country, or complete gibberish and lies from morning to night.

WEDNESDAY

Instantly, on hearing of the death of Pope Benedict on Saturday, we decided that we had to go to Rome. It meant cancelling other plans and cutting short a trip down West, but this man had been such a torchlight of understanding in our lives that we could not sit out this moment in European history without participating in some way. We managed to book our flights before the airlines cranked up to their standard level of gouging, and booked a passable-sounding hotel, Hotel Teatro Pace, since our beloved room facing the Pantheon was already spoken for. This hotel dates from 1560 and is the most extraordinary building, dominated by a massive stone staircase that occupies half the space inside, comprising 90 steps over four floors, with — since there is no lift — seats, or a chaise longue at every return, so the crocked resident can have a little rest or three on the way up. It is three years since we have been to beloved Roma, and I would like to say something more about it, but space prevents me this week as I have other fish to fillet. I believe I may return to the topic of Rome and the Italian people in next week’s diary.

I have already written a great deal about Ratzinger/Benedict, and my article of Sunday last immediately took off and by the time of his funeral, it had become the third highest viewed of all my articles here in the past 27 months. The popularity of Joseph Ratzinger is one of the best-kept cultural secrets of the present age. It is as though his life and personality speak for the way in which true sentiment and understanding have been driven underground by the pressure of the narrative, to emerge only wordlessly, in the unarticulated actions and behaviours of regular people. A dozen years ago, when he went on a papal visit to Scotland, the advance media consensus was that he was so disliked that nobody would show up to see him. It seemed that every single advance report about the visit, on the BBC and in the newspapers, managed to mention child abuse, homosexuality, Hitler Youth, ‘God’s Rottweiler’, women priests and condoms in Africa. Because of his reputation as a ‘dogmatist’ and ‘conservative’, he had become a convenient scapegoat for all kinds of anti-religious sentiment. The previews highlighted the protests said to be planned by some of his critics, the usual unfavourable comparisons between Benedict XVI and his predecessor, the alleged apathy on the part of British Catholics towards their leader, et cetera. Briefly glimpsing some television coverage of Pope Benedict’s arrival in Scotland. I was moved to sorrow for him. He looked alone in a strange and unfriendly place. The ‘welcome’ by Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip seemed perfunctory and cold. The initial stretch of roadway seemed almost empty as the popemobile moved towards Edinburgh city centre. I wished for the Pope that he could be sitting in Rome with his feet up drinking a cappuccino. A couple of days later, as I got on a plane for Philadelphia, a friend rang to tell me that he had been watching the continuous coverage of the pope’s visit on TV and it was ‘amazing’. On my return I began to grasp that something great had happened. I heard the visit being described as a ‘triumph’ on — unbelievably — the BBC. Everywhere he went, the Holy Father had been greeted by tens, hundreds of thousands of cheering people. The ‘story’ was no longer hostility or apathy, but how the Pope had touched the British nation and provoked it into joy.

Something similar might be said about his funeral. Rather than a ‘triumph’, it was yet another salutary moment in our sad and deepening situation. But, again, the advance prognostications were shown up as risible. The standard prediction was that something like 30,000 people might show up, a fraction of the attendance for the funeral of his predecessor, Pope John Paul II. But, by this unbelievably mild and sunny January afternoon, with more than 200,000 of the faithful having filed past the pope’s remains in St Peter’s Basilica, it is clear that, once again, the journaliars are caught on the back foot. Around 3pm, we join a queue of several thousand people in St. Peter’s Square. The attendance is a mixture of all ages, colours, nationalities and, probably, faiths, proving yet again that Joseph Ratzinger was respected by the unseen, unrecorded world as one of the greatest thinkers of the age. Around us in the queue are sundry people in their twenties and thirties, several similarly-aged couples with their little children; a gaggle of nuns; a male gay couple holding hands; the Archbishops of Dublin and Armagh; a young man from Spain of our acquaintance called, arrestingly, Jesus.

The queue moves briskly forward under the supervision of the stewards, and we go from the security checks to the altar of the basilica in roughly an hour. For me, it is a deeply moving — I mean upsetting — occasion, as I am remembering the day back in 2005 when Cardinal Ratzinger stepped out on to the balcony as the new pope-elect. It seeming impossible — that such a great, great man might get a chance to put his mark on the Church and the world.

He did and did not. His many books survive to give an account of our times and his meditation upon them, but his chances of redirecting the Church from its path towards sentimentalism and therapeutism were foiled by a hostile media and the internal plotters who wanted no such thing. In the end, as we know, he aborted his mission and walked away. Perhaps one day we shall learn precisely why.

THURSDAY

Regardless of his critics and enemies, Pope Benedict’s eight years as pope stand now as a beacon of hope and clarity, as though to assure us that all might still be well. Virtually alone in the Europe of those initial years of the third millennium, he spoke for the fundamental values on which our civilisation was raised up, and fed the imagination of his time with concepts and images of the defining Mystery that resides at the back of reality. That all this is currently being trampled underfoot should concern us greatly — of course it should — but the good that Ratzinger/Benedict sought to bequeath the world has not been interred with his bones. It remains, on paper and in the hearts of his people — those who were paying attention, who heard and understood, at least in part. I do not always find myself in agreement with (the Catholic writer) George Weigel, but I cheered when I read in First Things where he described Benedict as ‘arguably the most learned man in the world’. Yes, and by a long chalk. He it was, above anyone, who stood against the tide of senselessness now threatening to engulf us, and, as I wrote earlier this week, when the moment comes when we reach the tipping-point of comprehension due to the hard impact of consequences, his words will be the first recourse as we scramble to locate an antidote to outright disintegration. It is so strange that he should leave us on the last day of 2022, so that we awake to this new year, as though abandoned to our fate. But no: His every word says otherwise, and that is the whole point, and why we so urgently need to start paying attention.

The era of the ‘two popes’ is over, then, and so we wait to see. Bergoglio, of course, represents the social and philosophical antithesis of his predecessor in the chair of Peter, in that he pushes the ‘watered-down, appeasing’ type of Christianity that Ratzinger abhorred. The nearest we hope ever to encounter to a ‘Woke Pope’, he seems to approve of — and be approved by — the kind of agenda-driven interests implicated in the persistent attempts to take down the West.

It is notable, at the funeral Mass, that whereas the coffin of Benedict is greeted by waves of applause as it is borne on to the altar, the present incumbent of the chair of Peter receives no acknowledgement from the crowd.

Bergoglio presides over the funeral Mass, though without noticeable animation. He remains in a wheelchair for most of the ceremony. He looks older than Benedict did, and much, much wearier, perhaps even confused. His choice of theme for the homily is odd — understated and obscure — and he reads it from his script in mechanical style, without visible zest and without taking his eyes from the page. The theme is the entrustment by Jesus of His spirit to the custody of the Father, ‘which led him also to commend himself into the hands of his brothers and sisters,’ accepting everything that has been laid down for Him. Only in the final sentence does he refer directly to his predecessor: ‘Benedict, faithful friend of the Bridegroom, may your joy be complete as you hear his voice, now and forever!’

The homily is bereft of even a hint of the affection said to obtain between the two men. A local priest friend afterwards asks me what I thought of it, and I say that it was like a generic sermon delivered at short notice by a country parish priest. ‘Yes,’ he replies, ‘but the parish priest would have delivered it better.’

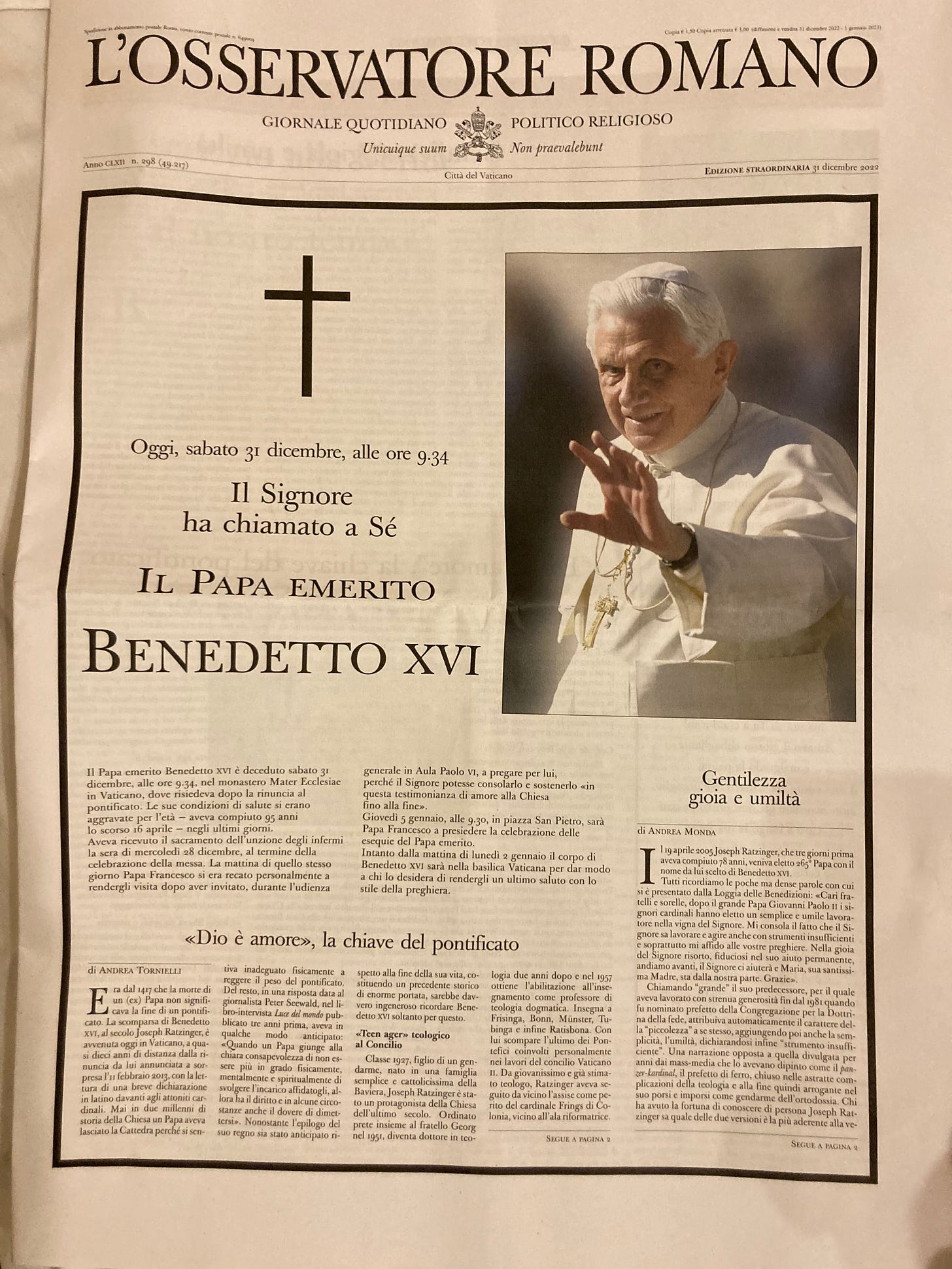

A mist hangs over St. Peter’s Square, beginning to clear only as the service comes to an end. It is colder than yesterday, as befits our mood. As we leave the square, the mist seems to change its mind and regroup. A woman hands me a copy of the latest Osservatore Romano, the official Vatican paper, for which I have occasionally written, though not in the Time of Bergoglio. The headline says ‘Il Signore ha chiamato a Sé: Il Papa Emerito Benedetto XVI’ — ‘The Lord has called to Himself Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’. It strikes me that, in the near decade since his abdication, I have never once heard anyone but an official spokesperson or clergyman refer to Benedict as ‘the Pope Emeritus’ — the makey-up title they gave him back then ‘to avoid confusion’ (haha!). Regular people called him ‘Pope Benedict’, or ‘Papa Ratzi’, or simply ‘The Pope’. That he was, and that he remained to the end.

For once these Irish words are literally apposite: Ní bheidh a leitheid ann arís: We shall never know his like again.