Advent Reappraisal, 2023: The Sleepwalk of Unreason

An Extract from my 2010 Book 'Beyond Consolation: How We Got Too Clever for God and Our Own Good,' exploring — or exposing — the 'rationality' of a belief in nothingness and ‘extinction.’

The Poetics of Nothing

This post may be too long for the Substack newsletter format. If you’re reading it as an email and it tails off unexpectedly, please click on the headline at the top of the page to be taken to the full post at Substack.

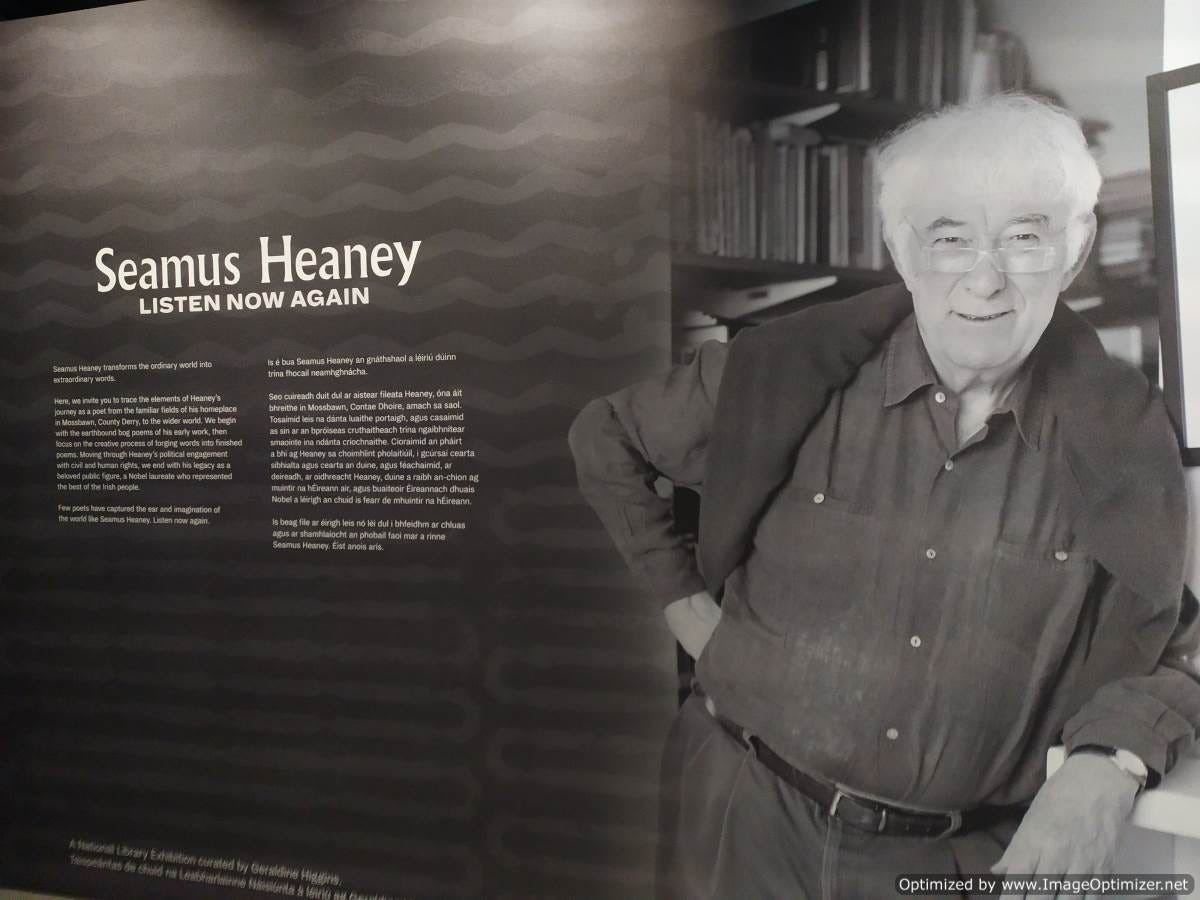

In April 2009, Ireland was pleased to honour, on the occasion of his 70th birthday, the Nobel prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney. On the national broadcasting station, RTE, there were many radio and television tributes to this distinguished Irish writer and his work. On the Marian Finucane Show, [on RTE Radio One] a year to the day after Marian had interviewed her dying friend, Nuala O’Faolain, the poet was the subject of a lengthy interview, in which the conversation ranged over many subjects, including religion and the idea of an afterlife. I record the occasion for a number of reasons. One, that it is reasonably typical of the way such matters are dealt with in our culture today. Two, that it illustrates how existing ideas can be affirmed by an authoritative voice. Three, that it indicates how a particular definition of reason has been enabled to develop without ever coming under pressure to justify itself.

The poet said a number of things in the interview which were picked up by several newspapers and reported without significant comment or analysis. Because the author of these statements was not merely a poet, but a Nobel prize-winning poet, they acquired a significance far beyond their intrinsic content. In Ireland, poets are still seen as possessing some kind of ‘other-worldly’ insight, and the pronouncements of an internationally celebrated poet are therefore to be considered to have far more cultural power than those of almost any other category of public figure. In introducing the poet, Marian Finucane quoted the writer Joseph O’Connor as declaring in an article in one of the day’s newspapers that Heaney was ‘like an ancient bard, a druid who knows all the secret rhythms and rhymes of his time. He speaks for us all’. Allowing for a little rhetorical hyperbole, few would have demurred from the underlying idea that Heaney, by his work and stature in the wider world, had earned himself the role of a kind of Irish shaman of letters.

After some perfunctory questions about his winning of the Nobel prize, Marian Finucane asked Heaney about the fact that, some years previously, he had suffered a stroke which led him into a close brush with death. Through her work on behalf of the hospice movement in Ireland, Finucane had been to the forefront of many campaigns and debates concerning death and dying, and how society should treat those who find themselves in the final stages of life. It is likely, this being almost the anniversary of her interview with Nuala O’Faolain, that this issue was looming even larger than usual. Going through both his writings and interviews, she said, she was not quite sure that she knew where Heaney stood ‘in terms of religiosity and death and faith’.

Heaney said he never thought of his illness as a brush with death. He had been paralysed down one side, but his speech and memory had been unaffected. ‘I felt anxious but I never thought, “God I’m going to go”.’ It was impossible, listening in, to avoid the idea that he was ducking the question.

Marian Finucane then asked him straightforwardly about his attitude to religious belief. He giggled a bit and said that he was about to ask her the same question.

Pressed further, he began to explain that he had been reared in a traditional rural Catholic family. ‘I think anyone born in our country, in our culture, certainly in my generation… the shape of the world, the religious eternal dimension was a given dimension in our world. And that sense of another dimension, the fundamental religious view, I think I will never lose that. Of course, the first part of my life, the sense of religion was rewards and punishments, heaven and hell, judgment at the hour of death, and the fear and trembling of that. Now, over the years that has disappeared. Obviously.’

And Marian interjected: ‘Has it?’

‘Yes. I mean extinction. Yes.’

‘You don’t believe in extinction?’

‘I do believe in extinction. That’s what happens.’

So there it was. ‘Nobel Prizewinner Says There Is No God.'

It is an interesting word, ‘extinction’. It has several meanings, all closely related, although in the way the poet used it, it had a clear and emphatic meaning. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines ‘extinction’ as ‘the state or process of being or becoming extinct’. The word ‘extinct’ is itself defined in several ways, the relevant ones here being: ‘(of a species, family, or other larger group) having no living members’; and, ‘no longer in existence’. The word has an etymological connection to ‘extinguish’, defined as ‘cause (a fire or light) to cease to burn or shine’. It is striking that the poet did not intend a precise, literal equivalent to any of these meanings. He was talking about individual human beings, not of the species or any group within it. He clearly meant to convey something to the effect that when man dies he is ‘no longer in existence’. This seems axiomatic: a dead man is clearly not ‘in existence’ in the way he was when alive — he has, in a precise sense, been ‘extinguished’, as a candle is extinguished when the flame is put out or dies.

Not even a poet can imagine what this might be like, or indeed if it is ‘like’ anything, since the process of comparison necessarily supposes a capacity to compare. If one has entered into nothingness by virtue of what Seamus Heaney would call ‘extinction’, it is doubtful if one would retain any capacity to apprehend what one encountered, since ‘one’ would not exist and therefore could not be said to encounter anything. Such an entry into a total absence of consciousness appears to be what Heaney had in mind for himself and everyone else. But in naming it — ‘extinction’ — he was relying on conventional assumptions which do not necessarily have the kind of reasonable basis that Heaney’s rather telegrammatic disposal of the matter implied.

The very word ‘extinction’ in this context, as used by Seamus Heaney, is tautological. Anyone, regardless of belief, might loosely use such a word in observing that human life is extinguished by death. A religious person might loosely employ such a word to convey the process of the mortal body becoming subject to the inevitable, since an acceptance of mortality does not in any sense preclude the possibility of an afterlife. But Heaney used the word ‘extinction’ in a slightly different way. There was a hint of challenge both in his choice of word and in his delivery of it. In uttering it, he was confronting something, albeit something unstated. He was volunteering the weight of his poetic ‘office’ to make a reinforcing point on behalf of the prevailing culture. He was making a choice and doing so consciously. He was not making a neutral, passive statement, but denying something that for many people is of momentous importance: the idea of eternal life.

We throw the word ‘nothing’ around as though it were obvious what it means. But there is no such entity, knowable to the vast majority of humankind, as Nothing. A few mathematicians and philosophers may have some tenuous grasp on some abstract sense of what Nothing is, expressing it as zero or emptiness or vacuum, but for most of us this remains an abstraction. We cannot conceive of it. ‘Nothing’ is beyond our grasp, like Infinity and Eternity and the Absolute. Nothing is an inverted reality, one that does not exist for us, even in its non-existence. We know nothing about Nothing. And yet, although we readily throw cold water all over the idea that a human being might live for ever; or that our humanity is an infinite phenomenon that, like matter or energy, cannot be destroyed; or that the reality we inhabit is part of an absolute reality that cannot be comprehended by our tiny minds; we speak of Nothing as though it were the most self-evident concept in existence, throwing the word around as if we had meditated upon the question at great depth and came up with words which by their very existence and in their essence contradict the concept we are seeking to communicate. Nothingness, extinction: names for things that cannot be seen or known. How, then, can they be named?

For a human being to think about nothing, not to mention think about Nothing, would require the thought and the human thinking it to disappear, and for the space from which both the human being and the thought had emanated to be absorbed into an absolute nothingness containing neither space nor matter, a non-entity that could not possibly exist and could neither observe nor be observed. No, it would require more: it would require this not to have happened, for time to reverse itself and erase even the possibility of such a human ever existing, never mind having such a thought, and for time then to curl itself up into a ball and evaporate itself into something that could not be air or space or anything at all, but would not be amenable to sense or description, even if these phenomena could exist without the intervention of humanity, which of course, because humanity had never existed or had become ‘extinct’, they could not. And by the evidence of anything you care to mention, even just the evidence of this sentence, this could never happen, or not happen, or not even be contemplated, which must surely mean, if it means anything, that Nothing does not exist. There is no Nothing. Nothing is not a thing we need to think about.

The nearest a human being can come to conceiving of Nothing is to wave his hand in the air, a ridiculous parody of an irrational idea. For what he engages with here is not Nothing. It is something: air. It bears no relationship to the concept of Nothing (if Nothing can even be a concept), may even be the opposite of Nothing (if Nothing could possibly have an opposite, which, being Nothing, it could not) because the concept of Nothing does not exist, or if it does we cannot imagine it, for in trying to imagine it we deny its existence and negate its very possibility. Or, perhaps that should be ‘non-existence’ and ‘impossibility’, for Nothing is a very confusing thing.

We use words in an attempt to convey Nothing, even though the words by their existence make this impossible, in the same way as it is impossible for a play or a book or a film – or even a poem – to convey boredom without the description itself being boring. We speak of Nothing as though it were an everyday thing, like water or chocolate, something that any ten-year-old could grasp and pack up into a little bundle of established and incontrovertible truth, and stash it away to be deployed in the course of thinking processes for the whole of a life surrounded by Somethings but no Nothings and handed on to children who must necessarily have emerged from this Nothing to do the same thing.

And we call this reason. It is not reason. It is laziness and unthinkingness and sheer intellectual sloppiness of a kind that would make Pooh Bear seem like Spinoza. The wonderful thing about rigour is rigour’s a wonderful thing.

A belief in Nothing, or in ‘extinction’ may appear knowing in the culture we have created, but it is, so to speak, nothing but pessimism. It is despair dressed up as realism.

A key governing idea of present-day culture is that a perspective that looks into the eyes of the universe and concludes that there is Nothing rather than Something is the height of cleverness, that it is smarter than anything else, that it has been arrived at by a process of logical husbandry of the known facts. In contradistinction to the ‘superstitious’ and ‘obscurantist’ mind-set of religious believers, the culture insists, in both words and gritted silence, that this outlook is, self-evidently, more intelligent and reasonable. And yet it is difficult to avoid the suspicion that this viewpoint is held to, in the same way as religious belief and to perhaps an even greater extent, by the stupid as well as the brilliant, the slow and the razor-sharp.

It is easy to say that you believe in nothing, that there is no God, no heaven, no afterwards, no hope. The culture is currently well adapted to making such a statement seem intelligent, when actually it is as vacuous as the abyss it proposes as the destination of everyone. It is the laziest form of thinking masquerading as the most refined.

We have no way of knowing for certain that life, like the body, does not simply change form. Reason has no means of, and no reason to, deny that, if the physical matter of the body simply undergoes a metamorphosis, then the same thing may happen to the life, that the relationship between the human body and the human soul is not analogous to the relationship between the candle and the flame. There is no definitive proof one way or the other. We just cannot say. Anyone is entitled to speculate, but nobody can say with any more ‘reasonableness’ than anyone else, or at least not in the language of what is conventionally called ‘reason’. And a poet is no more entitled than a plumber to have his declarations on these subjects regarded as ‘expert’.

Sitting in the studios of the national broadcaster, the most celebrated Irish poet since Yeats had declared that what we see is all there is. Speaking not just of himself, but of everyone who was listening and everyone who was not, and summoning up all his poetical authority, he declared human reality to be defined by an abyss of unconsciousness and death.

But soft. When asked if he believed in ‘redemption’, Seamus Heaney sought, as had Nuala O’Faolian a year earlier, to complicate things a little. It was, it has to be said, an odd question with which to follow up a declaration of nothingness as the aftermath of the human journey. Can the extinct be redeemed? Why bother? Redeemed from what? Why?

It is a symptom of what has gone awry with the Irish sense of the religious that this question would probably have made a kind of sense to most of those listening. Irish people expect discussions about faith to follow certain lines and employ certain buzzwords whose meaning is woolly but still approximately comprehensible. ‘Redemption’ is one of those neatly tied bundles of agreed meaning that seems to fit as a way of prolonging a discussion that is tacitly agreed within the culture to have no real basis in reality, but which nevertheless enables discussion to continue without ever becoming particular. In the Christian context in which it was here being used, the word ‘redemption’ signifies something about Christ having died to save mankind from the consequences of sin, or perhaps having risen to indicate the possibility of an eternal hope. Already, it was clear from Seamus Heaney’s initial response that he attached no substance to either of these interpretations. This did not necessarily make Marian Finucane’s question, ‘Do you believe in redemption?’, a bad question, though it might reasonably be considered a non-sequitur given what Seamus Heaney had already indicated about his beliefs.

‘I believe in redemption’, he replied. ‘I believe in faith in this life. The Christian message is about faith in this life. It is about redeeming and being redeemed by . . .’ He paused. ‘The message is one thing. The doctrine at this stage is not as practised, not as binding on the general whole church itself. I mean apart from the Curia, I suppose, those entrusted with the Magisterium, the teaching of the Church, I think that clergymen, sisters, nuns, the official Church is much less dogma-bound than it was. And I think that the faithful, so to speak . . . I mean my feeling is that the faithful are less, ah, less orthodox, certainly than they were.’

It is difficult to know where to start in attempting to parse this response. The stuff about the Curia and the Magisterium is the kind of thing people of a certain age engage in to convey that they are well versed in ecclesiastical terminologies, thereby signalling that anything they say has a greater value than might otherwise be apportioned it. ‘Doctrine’, ‘Curia’, ‘Magisterium’, ‘dogma’, ‘faithful’, ‘orthodox’: none of these words, in the contexts he employed them, would have meant anything much to most of those listening, other than to signify that the subject under discussion was ‘Religion.’

Does ‘faith in this life’ refer to the quantity, or quality, of faith exercised in this dimension or to the idea that this existence alone is worthy of faith? Based on Heaney’s earlier answer, one presumes the latter. But how can you have ‘faith’ in something that is self-evident? Or did he mean something else? If so, what? How about this: that he does not believe in faith in God, or in the idea of an afterlife, but he believes that the idea of faith is itself a good thing? In other words, that, even though God does not exist and there is nothing awaiting us but extinction, it is healthy to believe in something, even though this something may be invention or falsehood?

The idea that the Christian message is 'about faith in this life’ might have seemed interesting if most of the possibilities it opened had not already been dismissed in Heaney’s initial verdict of ‘extinction.’ The idea that Christianity should be about living here and now in this dimension, rather than directed purely at some putative future existence, might have prompted an interesting philosophical discussion; but, given that Heaney had already emphatically ruled out the possibility of any future existence, it was difficult to avoid inferring him to mean that Christianity is actually a spurious programme of pseudo-spiritual engagement designed to make the earthly existence more palatable for everyone. It might well be argued that Christianity is ‘about faith in this life’ in the sense that it proposes the idea of faith as an answer to the fundamental questions of existence. It does not, however, propose that the meaning of life is centred on this existence. Theologically speaking, these are diametrically opposing positions: one, a widely held view among theologians, holding that Christianity invigorates this life with its promise of the next; the other, a decidedly untheological view, that the whole thing is a benign concoction to get people to behave in a civilised manner.

Of course, Heaney was not expressing any theological or philosophical position, he was simply blathering.

‘And if anybody like myself goes through a literary education,’ he went on. ‘Everything in twentieth century literature, everything really in nineteenth century literature, or from the Enlightenment on, is a challenge to orthodoxy. So it’s quite possible to live with a religious sense of the world, to live with complete faith in the Beatitudes, Christ’s Sermon on the Mount, to know that this Christian ethic, ethos, is the one that you belong to and that it is, as far as I can find, the best method yet of proceeding.’

What does this mean? As a statement on what might be deemed one of the central questions of human existence, it seems evasive and confused. In name-checking the Beatitudes and the Sermon on the Mount, Heaney was again signalling his familiarity with the chapter and verse of Christian culture. It would be surprising, indeed, if he was unfamiliar with these. But what is surprising is that he did not appear to have given any thought to the idea that, without the core meaning of the Christian proposal, the Sermon on the Mount would not long retain its cultural power.

And what could possibly be meant by the suggestion, coming from someone who believes in ‘extinction’, that the Christian message is about ‘redeeming and being redeemed’? Yes, redemption has a precise meaning in the Christian context, but it seems that Seamus Heaney had something different in mind. If there is nothing afterwards but extinction, then the Christian idea of redemption is bunkum, and Christ was a lunatic with a God-complex and long hair. The poet seemed to have some other idea of redemption, perhaps the idea that suffuses the modern artistic sensibility, of a form of psychological cleansing brought on by cathartic events.

Marian Finucane, in her polite but firm manner, was indicating that she had picked up the vacuousness of what the poet was saying.

She asked him: ‘You say that it is on this earth that we find our happiness, or not at all, whereas you presumably were reared as I was, that it was in the next life that you find your happiness . . .’

Heaney answered: ‘Yes of course, but I’m saying that, ha aha ha, that disappeared, quite . . . I mean who . . .who on earth now, with a few orthodox exceptions I would say, believes that their reward is in eternity? I mean who among the Irish middle classes, sits up at night and thinks that? Maybe I overestimate that, but it’s a . . . it’s a . . . it’s a hazy area for those brought up with belief.’

There was that word ‘orthodox’ again, the suggestion being that a belief in something beyond the material world we know could only be a symptom of unquestioning adherence to an imposed world-view.

Who on earth believes that their reward is in eternity? Er, quite a number of people actually. Anyone who accepts the Christian proposal, for a start, which in Ireland would still account for a majority of the population. This is what religious belief involves.

Who among the Irish middle classes sits up at night and thinks that his or her reward is in eternity? All the poet has to do is walk to his nearest church on any given Sunday and ask people coming out. Where else might Christians think their ‘reward’ is to be found?

And what is meant by this: ‘Maybe I overestimate that, but . . . it’s a hazy area for those brought up with belief’? Has he in mind people like himself who have been brought up as believers but who no longer believe? Is he saying that he is unable to conceive of anyone having had such an upbringing and continuing to hold in adulthood to the belief in God or the hereafter? No other interpretation is possible, since, clearly, for people who have not been brought up as believers, the idea of eternity is not hazy at all. Either they believe it or they don’t. For people brought up as believers, the situation is exactly the same: they believe or they do not.

Maybe he overestimates what? Maybe he overestimates the idea that eternity is still understood as the reward that follows earthly existence? Since Heaney clearly believes that nobody among the Irish middle classes believes in this, he is implicitly saying that this view is held, apart from by ‘the orthodox few’, by the poor and uneducated only, groups not embraced by his category ‘the Irish middle classes’. Maybe what he means is that maybe he overestimates the importance of the belief in eternity as a constituent element of religious belief. But of what, other than a belief in eternity, does religious belief substantively consist? Of course it is much richer, much broader than that, but belief in eternity is necessarily at the core of it. There is no avoiding, no fudging it. There is nothing in the least hazy about it for those brought up with ‘belief’, which holds to the idea of eternal reward with the tenacity that a jockey holds to a horse. Or at least it is not the experience of being brought up with belief that renders it hazy, but other things: extraneous elements, desires, agendas, intentions. If it is hazy, it is because the culture has rendered it so. It has nothing to do with the belief itself, which could hardly be clearer for those who hold to it. Believers may doubt sometimes, but there is no scope for haziness.

Then Marian Finucane asked him about materialism — how money had become ‘something of a religion’ in the previous ten years or so. Heaney eagerly picked up this ball and ran with it, observing that Ireland had been in danger of losing its ‘religious unconscious and its Christian unconscious’ during the years of the Celtic Tiger. The downturn [of 2008], he declared, ‘may have happened in time’.

‘I thought the capacity for adaptability went far too far, adapting to capitalist, materialist, consumerist values. And the protection, the self-protection of the culture we had, which was community-based, caring-based, charity-based, a kind of post-religious, if you like, sensibility. We had a religious unconscious, even though we mightn’t have been so . . . and we had a Christian unconscious, the idea that you could live on very little, that self-denial was a virtue, that there was a kind of virtue in helping others. That slipped, it seemed to me. And maybe what’s happened happened just in time to re-brace the inner beings and the society generally.’

This, together with his assertion that Christianity is ‘the best way to proceed’, amounts to an odd position for someone who does not believe in the central idea of Christianity, which is that death shall have no dominion over mankind. Let us state it clearly: Seamus Heaney, for all his pessimism about the ultimate destination of humanity, thinks those who have been spinning untruths to the Irish people have been carrying out an important public service in laying down the ‘Christian unconscious’, presumably because this refers the human enterprise to a broader level of awareness than the purely material. It is a position that seems to discount the centuries of Christian belief as empty superstition and yet to patronise this culture of belief as upholding something worthwhile for mankind.

From certain of his inflexions, one infers that the poet seems to regard any erosion of the ‘Christian unconscious’ as a bad thing — to hold that the collateral benefits of empty superstition are to be celebrated and valued. But the question then arises: how could such values be perpetuated for very long after the ‘knowingness’ of mankind, which he also appears to celebrate, had succeeded in debunking the underlying beliefs? Is Heaney’s interest in this of a purely anthropological nature, or is there some element of moral judgment in his attitude? Certainly, from his apparently favourable references to the benefits of a ‘Christian unconscious,’ it seems that his interest is at the level of social morality. And yet he not only appears to hold that it is acceptable that this morality be founded on a lie, but that it is also a positive development that the lie has been rumbled by all but the most orthodox and/or ignorant.

And there is a deeper problem in that Heaney’s attitude appears to almost melt out of time, to remove itself from the immediate implications of his beliefs. By this I mean that the speaker appears to be indifferent to the question of how the moral cohesion that he extols, and which he traces to the influence of Christianity, might be perpetuated in the absence of the superstitions providing what might be termed its ‘glue’. In this the poet exhibited a strange quirk of the modern mindset, which believes in the increasingly irreligious enlightenment of the species in relation to the ultimate meaning of reality (extinction and so on) and yet seems to agree with those of a religious disposition who argue that religion is essential to the moral cohesion of society.

This appears to suggest that, without religion, there is at least a risk that morality will be reduced. But what, as the exam questioner might have posed the question, is the poet’s view of this? Does he think that something else will crop up to replace religion as the moral glue of society? Does he believe that the moral cohesion wrought by religion can continue even after its roots have been cut? Is he blind, or devil-may-care concerning what happens next? How, in other words, does he tie the whole thing together in his mind? Or does he?

Of course it is possible to have no religious beliefs and still believe that religious beliefs are good for society. The believer may take the view that such a stance is somewhat hypocritical, since the unbeliever contributes nothing to what he says is in society’s best interest. But the unbeliever cannot be blamed for this situation. He cannot help his unbelief. Faith is not something you can simply will into existence. At the very least, you might decide, the unbeliever who acknowledges the good that has flowed from religious influence must be given credit for magnanimity, for generously conceding the value of something he himself believes to be bogus. Many believers tend to take comfort from such contributions by those who say they do not believe in God or the hereafter on the basis that at least they are not actively opposed to religion in the way many self-declared atheists tend to be. But there is, nonetheless, a semantic difficulty with this position. How, after all, if you do not believe in God or in the afterlife, can you reasonably suggest that a Christian consciousness is a positive phenomenon? You might observe that this has had a role in the civilising of man, but would also have to allow that, on your own declared terms, this civilisation has been based on falsehoods. What, then, do you propose will function in the place of these falsehoods when everyone becomes as enlightened as you are?

Seamus Heaney, it was clear, had already decided his position on these questions for himself, which is his absolute right. But here he was going further and asserting that the idea of eternity is so far-fetched that no thinking person, never mind a right-thinking person, could possibly hold to it. The entire drift of his thinking on this subject could be summarised as follows: we are now too clever to buy into the idea of God and the hereafter, but we still need the rules Christ gave us so as to live together in any kind of harmony. Implicit in his remarks is the idea that, paralleling mankind’s growing belief in his own increasing cleverness is a process of undoing by which the rules we have come to live by are being undermined. This is the logic of what he was saying, and is perhaps a more interesting idea than anything he actually stated. Yet at no point in the interview did he seek to underline it, to claim it as his own. Instead, he remained content to state things that were no more than repetitions of the mantras of the secular culture he seemed to be conscious of addressing. He may well have been expressing a sincere personal perspective, but he was also saying something that he might readily have expected the listening culture to find unexceptional.

At no point in the interview did Seamus Heaney elaborate on why he believes the idea of eternity is nonsense; he just appeared to assume that everyone listening to him would agree that it was, and that this was an opinion one did not need to have arguments for. Interestingly, his interviewer did not press him to move beyond his comfort zone. Neither was he required to produce arguments for the other semantic and logical flaws in his position.

A generation before, in a culture characterised by the most pious forms of Catholicism, such fuzzy philosophisings might have seemed to amount to a radical perspective and might well have involved the poet in a significant controversy. Now, however, his viewpoint was not unusual, even for a poet. Seamus Heaney was availing of a mechanism in the culture that, having already established absolute wisdom on these matters, requires only that the speaker nod in the direction of the prevailing assumptions in order to avail of the culture’s consensual and intellectual protection. He was invoking on his side of the argument the culture of quasi-reason, which enabled him to make a point about a central question of existence without having to offer anything substantial in the way of evidence or argument.

It is, of course, possible to disbelieve in God, in creation and in the hereafter, and yet to believe in the idea that manufactured beliefs in these phenomena may have beneficial consequences for human society. But, if I believed this, I would, I hope, be at least the smallest bit interested by the idea that, now my own disbelief was being shared by growing numbers of my fellow citizens, we must be getting closer to a moment when the glue would begin to melt. I could not console myself with the idea that, whereas the superstitions I could so readily discredit and debunk were now being brought more generally into question, they had already fulfilled their useful function in creating the moral framework which enabled me and my fellow citizens to live together in a benign, ‘post-religious’ sensibility. If I believed these things, I would, I think, be all the time jumping ahead to ask what might happen when the superstitions eroded a little more. How would all this work in a hundred years? Can we be complacent about the chances of future generations being able to carry off the same pretence as ourselves?

If my position were anywhere close to Seamus Heaney’s, I expect I might either construct a rationale based on the idea that man is capable of constructing a moral framework without reference to religion — which did not appear to be the poet’s position — or I would be forced to imagine some apocalyptic scenario in which an increasingly clever population of middle-class sceptics started to boil each other’s children with cabbage and potatoes.

But what Seamus Heaney appeared to be thinking was that the model he had grown up with would serve perfectly well for the moment; that, after a recent period of concern, he was now reassured that the civilisation of which he approved, built on the lies he had rumbled, was looking more safe. There had been a slight hiccup in the years of the Celtic Tiger, when people started to go a bit mad, but now things appeared to be getting back on track. Perhaps, one surmises, the shock of the downturn had sufficiently scared the population to return if not to the superstitions, then at least to the moral framework constructed upon them, clinging more tightly to the lies at the heart of their civilisation.

Interesting, too, beyond the content of Heaney’s expressed opinion, was the way that, in the truncation of the discussion following his formal declaration of imminent extinction for everyone, a sense was conveyed that his verdict was, if not self-evidently conclusive, then certainly emphatic. The poet had issued his judgment and so the listening public was, depending on what each listener believed, either confirmed in a creeping suspicion about reality or challenged in a way that was impossible to answer. Heaney was working within a scheme of cultural logic that allowed his opinion to add itself lightly to the conventional assumptions he was feeding off and going along with. It was just a tiny incremental adding to the assumptions already ‘established’, but solid enough to add another microscopic grain of certainty to the prevailing cultural understanding of things. Either in the interview itself, or in its dispassionate treatment in the wider media, no resistance was offered to his views, which were accordingly conferred with an aura of conclusiveness.

What I found myself objecting to in the interview, then, was not Heaney’s beliefs or disbeliefs. The point is not that I disagree with him, although I do, but that I am just a little shocked that someone of his intellectual stature should be so loose in his thinking concerning the core questions of existence. Even more shocking is that he was put under no pressure to account for his opinions.

What bothered me about the interview was that it was the statement of someone who has acquired the status of a cultural guru, and who, invited to say what he believed about the meaning of life and death, invoked the history and language of Christian civilisation to suggest that the central ideas that underpin this civilisation are pure unadulterated nonsense. He was able to do this in the nicest way imaginable, as though he were not really saying anything of significance at all. Who, after all, could possibly object to a gentle, 70-year-old man sitting in a radio studio expounding his views of life and death? For one thing, it did not appear to occur either to Heaney himself or his interviewer that he might well have been striking despair and distress into the hearts of some of his listeners.

There are questions which Seamus Heaney might have been asked which might have either led him to elaborate on his disbelief or else exposed his words as unthinking repetitions of conventional wisdoms. Why, for a start, does he believe that nothing, or Nothing, awaits him beyond this life? Does he have evidence of this? Is this belief grounded in his experience? If so, on what? Does he believe in anything he has not been able to prove? If so, has he found this a reliable basis for writing poetry? He might have been asked if he had never laid eyes on his own children, could he have believed it possible that such beings could exist. He might have been asked if, seeing a caterpillar for the first time, he could have had any intuition of its turning into a butterfly. He might, in other words, have been taken out of the safety of the culture, to an intellectual space where his easy prejudices might have come under pressure. The reason he wasn’t is not necessarily that his interviewer shared his views — perhaps she did, I don’t know — but that the very exercise of delving into such an area of exploration would have issued a challenge not just to Heaney but also to the dominant culture, and thereby would have run a greater risk than simply letting the matter lie.

The Nobel laureate had questioned the very basis of the belief-system that had sustained Irish society for more a millennium, and yet the public prosecutor sat down implying she had no more questions. And in the silence there was an acquiescence which, perhaps more literally than we know, reverberated in the heart of every listener to that interview. Each of us, in the intimacy of the human heart, was free to dissent from what the Nobel laureate had just said, but such resistance had become microscopically, but measurably, more difficult by virtue of his having said what he said and Marian Finucane having clearly received his declaration as a statement of the axiomatic. Those who shared the poet’s view of the human destination were strengthened in their existing opinions by the fact that such a learned and celebrated man had endorsed their rational view of things. Those who had not shared this view, who held to a different sense of their humanity, were challenged by virtue of the same factors and, to a greater or lesser extent, infiltrated by dismay.

And yet the exchange had brought no new insights to the matter. The discussion had simply added something tiny but tangible to the edifice that man had already constructed on the bedrock he had floated on the mystery. Those listening were either vindicated in their pessimism or shaken in their hopes.

Doesn’t a poet have a duty to words and what they mean, and to ensuring that they make some kind of sense? Does a poet have any responsibility to the discipline of reason? Or can he just employ a colloquial form of expression to make observations that are, however loosely and lazily, in tune with the popular prejudices of the time? Is there any point, never mind any morality, in decrying the loss of a lie? Since this is unlikely to be Seamus Heaney’s settled view of these matters, does he not have a poetic, human or civic responsibility to draw these apparent contradictions more fully into the light?

Heaney would be unlikely to deny that he is the inheritor of a particular tradition in Irish poetry that traces its line not so much through Yeats, the Irish poet whose name is on the lips of the world, but on Kavanagh, who, for all kinds of reasons having nothing to do with poetry, is not (yet) as celebrated as he might be.

‘Is verse an entertainment only?’, asked Kavanagh in his poem ‘Auditors In’, ‘Or is it a profound and holy/Faith that cries the inner history/Of the failure of man’s mission?’

Kavanagh was a poet of the people who wrote a Gospel rooted in the countryside of Ireland, and for whom poetry was a moral and spiritual calling, a matter of theology rather than mere literature. His poems are rooted in the reality of nature and life’s perpetual cycle. They seek with every word to capture the invisible reality behind the everyday and the ordinary. A staunch Catholic who wrote eloquently of the spiritual hunger created in Ireland by moralism and piety, he did not regard literature as a means of chronicling the human condition, but as a chink through which we might peer into the fourth dimension of life, that aspect of existence that remains invisible but is always present.

‘The experience, as I see it, is really prayer’, his collaborator and brother Peter Kavanagh told me in a public interview in Dublin’s Trinity College to mark the centenary of Patrick’s birth in 2004. ‘Patrick believed in the divinity, so what he hoped was to get a flash of that beatific vision, that supernatural place. Words are the least important part of it. In a poem, words burn up in a tremendous thread of something unusual. The important thing was what we called “The Flash”, which was the Other World coming in to alert us to Its existence”.

Art and the artist stand in opposition to attempts by mankind to landscape the raw reality of his condition out of his vision. Social life, politics, commerce and entertainment try to convince us that our reality is knowable, controllable, manageable. Great art, like truthful religion (and they were once one) tells us that this is folly, that beyond our prefabricated, landscaped reality is an infinity of possibility, and that we did not, cannot and will not create one atom beyond what is already there.

In mankind, uniquely in the natural world, the mystery of existence becomes capable of expression. In our essence, we are the question which all art seeks to answer. The only requirement of the artist is an apprehension of the human situation, which is to say an awareness of the relationship between infinity and humanity. The true artist sees, hears of feels what is real, and reports faithfully the experience, in doing so reassuring us that, as Patrick Kavanagh put it, we are not alone in our loneliness.

Art has always had but one purpose: to kneel us before the mystery of our existence.

The essence of the mystery is within each of us, and the artist’s task is to find a way of expressing it that will not short-circuit into a conventional wisdom. In approaching the mystery, the true artist understands that the object of inquiry will recede at a speed exponentially related to the effectiveness of the approach. Humility, the admission of defeat in the face of infinity, is behind all great works of art. It is what we see when we are moved by a poem, a painting, a song or a story. In the surprise of the revelation, we glimpse what is unknown, unknowable, but, instead of being downcast by this undeniable failure of capacity and will, are buoyed up. Our very smallness becomes reassuring.

This, essentially, is what happens when we read a book or a poem that moves us, or see a play that we find ourselves acknowledging as ‘innovative’ or ‘interesting’. The epithets belong to the language of landscaping but the response belongs to our souls. The artist has taken us beyond the safe, landscaped area and enabled us to recognise ourselves. Each of us, in the intimacy of the heart, is touched, moved, changed, though outwardly we speak of intriguing plot devices, innovative chord structures and the subtle use of language. What touches us is something of the Source from which we come. There is a flash and we glance up, or prick up our ears. What was that? But ‘the Flash’ never affirms itself, is never more than a flash. It comes and is gone, leaving us bereft, confused but yet more certain of what we have witnessed. It strikes within us, resonating with the deepest desires of the heart, soothing our longing in the healing balm. It consoles, not because of some abstracted quality of beauty, but because it corresponds to the longing for perfection that resides at the centre of every human being. Without ‘the Flash’, a poem may still look like a poem. It may rhyme and scan and alliterate. It may even win the author a prize. But ultimately, without ‘the Flash,’ it is mere imitation, a calculated copy of something that, resonating in his heart, was mistaken by the poet for an interesting novelty, influencing him to create his own interesting novelty, now masquerading as a poem, by which someone else will be sufficiently impressed to render his own reinterpretation.

Much of what we nowadays call art is hand-me-down craftwork, the mimicking of form and composition by people who, because they reside in a culture that seeks to deny the transcendent, wish to be artists without shouldering the artist’s burden. Many paintings look like pieces of art but are actually mere compositions based on the idea of what art might be. The ‘novel,’ seeming to pursue the most literal interpretation of its name, appears intent upon the discovery of variations arising from its own history, the novelist having forgotten that what affects us is not novelty but recognition of the truth when we encounter it.

Similarly with theatre. I go to the theatre to watch a play which, in the end, allows me to leave with a mere sense of being ‘uplifted’, of having witnessed some psychological ‘catharsis’, rather than having been touched by the common chord of humanity’s longing for an external correspondence to its deepest desires.

Or I hear a song on the radio that causes me to pull over to the hard shoulder and sit wonderstruck for a suspended moment, but yet can continue about my business convinced that the reason I was momentarily slain in my seat has something to do with a clever interworking of musical traditions. The glimpse is lost.

There is a sense nowadays that ‘the arts’ are something that people need, perhaps in much the same way as they need the odd glass of wine or a bar of chocolate, or perhaps as some kind of added extra to the enjoyment of a civilised lifestyle.

Once, there was the artist, such as Patrick Kavanagh, who looked at reality and perceived the essential nature of things. Now there is the draughtsman, the wordsmith, the versifier who, reducing the function down to a form defined by page or canvas, makes marks which appear to correspond to those once made by the enchanted, but without the enchantment. When, occasionally by the laws of probability, it still happens, we are dumbstruck. We stare at something and recognise ourselves, or our place in the true scheme of things, and wonder if it can be an accident. We look at the artist, who looks like all the others. Did he know what he was doing? Is this just another accident or the real thing?

And if you ask, the chances are that you will encounter a denial, not because you have been mistaken but because the language in which you must ask and in which the artist must answer does not have the capacity to bear what you have both borne witness to. The experience you have just had may be an intentional wink by someone who shares the culture with you but does not wish to acknowledge that his quest is as your deeper responses lead you to suspect. Or, it may be that he has simply randomly recreated some reference he learned at art school, either without conscious intention or as an ironic commentary on the form in which he has chosen to express himself. Either way, the society recognises it as ‘art’, and on balance will adjudge it better if it is devoid of the conscious intention to summon up intrinsic meaning. Because the criteria have been reinvented by people who would become alarmed if the Flash manifested itself in their presence, what is valued now is not the glimpse of the Beyond but the quality of the mimicry or the juxtaposing of incongruous elements. We live in a world in which the denial of the absolute realities of existence is so entrenched and determined that artists, too, have been recruited as landscapers to produce evidence of man’s defiance of his apparent ultimate hopelessness. Artists are nominated as the consolers of a species that has decided, without much in the way of evidence, on its own intrinsic pointlessness.

I do not suggest that Seamus Heaney has not thought honestly and deeply about the great questions as did his precursor, Patrick Kavanagh. Anyone with even passing familiarity with his poetry knows this it not the case. ‘What’s the use of a held note or held line’, he asks in ‘Squarings’, in his 1991 collection Seeing Things, ‘that cannot be assailed for reassurance?’ This is a far more succinct, if cryptic, way of saying what I have been trying to say about his interview. And perhaps it can also be said of the entirety of his poetry, which, though beautiful and proficient, is an example of something that, as he implied of Christianity, exists only as a residue of something that once extended something more than mere consolation. For without a faith in the held line, there is no reassurance, no consolation, and without faith the line cannot long hold. If the held line becomes a held lie, how long can the fiction be maintained?

Nobody, then, could casually accuse Seamus Heaney of unthinkingness. And yet, in a single, short episode of public reflection, he contributed significantly to the unthinkingness of the public realm. Although his poems indicate that he reflects on the deepest matters at least as much as anyone else, and delivers the fruits of this imaginative voyaging in a language that opens himself and his readers up to the totality of possibility, he confined himself, when asked a straight, literal question in the context of a primetime radio interview, to the declaration that all his reflection, all his introspection, all his imaginative adventuring have led him to nothing except the conclusion that the material realm, the one we know, is all there is, with the implicit rider that the best we can hope for, from art or poetry or anything, is perhaps some kind of imaginative refuge from this reality, to be maintained and curated by people like himself.

Buy John a beverage

If you are not a full subscriber but would like to support my work on Unchained with a small donation, please click on the ‘Buy John a beverage’ link above.