A Conversation with Dr Eoin Lenihan

'Can we take our country back first, and afterwards decide what shape the world is?'

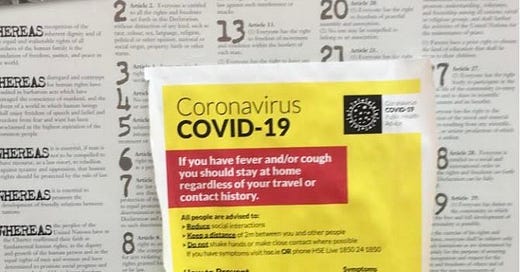

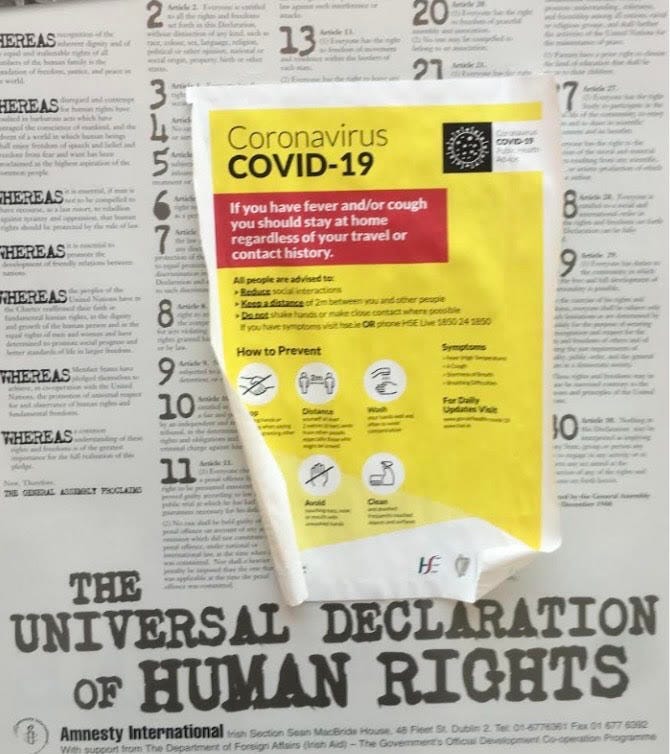

Notice in Irish police station, September 2020

Eating All Our Breakfasts

Should things take a certain course, The Abolition of Reality may become to the ‘story’ of the past five years what Winston Smith’s diary proposed it might become within the fictional world of Nineteen Eighty-Four. It is intended, first of all, as a permanent record of events that only a few noticed — in the depths of their meanings and significance — while they was happening: a book — as Winston said — ‘For the future, for the unborn’.

In that future it may be hard to persuade people that what happened from the spring of 2020 really did happen. Either the past will have been erased to such an extent that no one will know that human liberty ever existed; or else a revolution of human consciousness will make it improbable that human beings could ever have so easily been duped into surrendering the rights and freedoms which their ancestors had won in blood.

A fake pandemic was the signal that one morning began the foreclosure on everything that had, until the evening before, been axiomatically central to the idea of liberal, democratic, constitutional republics. The most shocking thing was not so much that this started to happen, but that almost no one seemed to object to it happening; almost no one sought to cite or defend the rights and liberties being overturned. Liberals fell silent; leftists joined in the clamouring for more and more tyranny. In The Abolition of Reality, John Waters describes not just what happened but the meaning of what happened, in the course of what may well be judged by history — if there is a historiography of the times to come — as the most heinous crime of all time.

This is a conversation which, like my new book, is about the whys and the wherefores rather than the whats and the whens, which we already know inside out. Dr Eoin Lenihan, a historian, invited me on to his channel(s) to discuss the content of my book, The Abolition of Reality (subtitled: ‘A first draft of the end of history’) and so we ended up discussing all kinds of themes that begin with Ireland and the Covid ‘Project’ and go off in multiple directions, including the preparatory history that came before, the historical assaults on family and parenthood, the ideological attack-dogs who prepared the way for tyranny, the ‘vital’ role of the ‘coincidental’ moral collapse of journalism, the construction of the pseudo-reality, the viability (or otherwise) of the Irish ‘freedom movement’, the possible intention behind the new pope’s choice of name, and much more besides. Just as Covid was not about Covid, but something else (‘your wealth, not your health’), the meaning of everything is different to what we are enjoined to believe.

The Abolition of Reality is intended neither as prophecy nor black pill. It is a ‘first draft’ of the ‘end of history’ in the sense that journalism is said to be ‘the first draft of history’. Right now, based on the various optics and trends, it is hardly possible to be optimistic about the eventual outcome, which may indeed be the end of our civilisation’s two-thousand year history. But things need not necessarily turn out like that. The content of any subsequent drafts depends on our preparedness to stand up and fight back. But first of all we need to take pains to understand the deep nature of what confronts us and our nations. The future is still ours to imagine and create. The final draft may well be the opening section of an entirely new volume, and it is up to us to ordain what it contains.

An arrestingly relevant extract from The Trial, by Franz Kafka, referenced in the book and the conversation.

Someone must have been telling lies about Josef K.

. . . because, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested on fine morning. Every day at eight in the morning he was brought his breakfast by Mrs. Grubach's cook — Mrs. Grubach was his landlady — but today she didn't come. That had never happened before.

K. waited a little while, looked from his pillow at the old woman who lived opposite and who was watching him with an inquisitiveness quite unusual for her, and finally, both hungry and disconcerted, rang the bell. There was immediately a knock at the door and a man entered. He had never seen the man in this house before. He was slim but firmly built, his clothes were black and close-fitting, with many folds and pockets, buckles and buttons and a belt, all of which gave the impression of being very practical but without making it very clear what they were actually for.

‘Who are you?’ asked K., sitting half upright in his bed. The man, however, ignored the question as if his arrival simply had to be accepted, and merely replied, ‘You rang?’ ‘Anna should have brought me my breakfast,’ said K. He tried to work out who the man actually was, first in silence, just through observation and by thinking about it, but the man didn't stay still to be looked at for very long. Instead he went over to the door, opened it slightly, and said to someone who was clearly standing immediately behind it, ‘He wants Anna to bring him his breakfast.’ There was a little laughter in the neighbouring room, it was not clear from the sound of it whether there were several people laughing. The strange man could not have learned anything from it that he hadn't known already, but now he said to K., as if making his report 'It is not possible.’ ‘It would be the first time that's happened,’ said K., as he jumped out of bed and quickly pulled on his trousers. ‘I want to see who that is in the next room, and why it is that Mrs. Grubach has let me be disturbed in this way.’ It immediately occurred to him that he needn't have said this out loud, and that he must to some extent have acknowledged their authority by doing so, but that didn't seem important to him at the time. That, at least, is how the stranger took it, as he said, ‘Don't you think you'd better stay where you are?’ ‘I want neither to stay here nor to be spoken to by you until you've introduced yourself.’ ‘I meant it for your own good,’ said the stranger and opened the door, this time without being asked. The next room, which K. entered more slowly than he had intended, looked at first glance exactly the same as it had the previous evening. It was Mrs. Grubach's living room, over-filled with furniture, tablecloths, porcelain and photographs. Perhaps there was a little more space in there than usual today, but if so it was not immediately obvious, especially as the main difference was the presence of a man sitting by the open window with a book from which he now looked up. ‘You should have stayed in your room! Didn't Franz tell you?’ ‘And what is it you want, then?’ said K., looking back and forth between this new acquaintance and the one named Franz, who had remained in the doorway. Through the open window he noticed the old woman again, who had come close to the window opposite so that she could continue to see everything. She was showing an inquisitiveness that really made it seem like she was going senile. ‘I want to see Mrs. Grubach . . . ,’ said K., making a movement as if tearing himself away from the two men — even though they were standing well away from him — and wanted to go. ‘No,’ said the man at the window, who threw his book down on a coffee table and stood up. ‘You can't go away when you're under arrest.’ ‘That's how it seems,’ said K. ‘And why am I under arrest?’ he then asked. ‘That's something we're not allowed to tell you. Go into your room and wait there. Proceedings are underway and you'll learn about everything all in good time. It's not really part of my job to be friendly towards you like this, but I hope no-one, apart from Franz, will hear about it, and he's been more friendly towards you than he should have been, under the rules, himself. If you carry on having as much good luck as you have been with your arresting officers then you can reckon on things going well with you.’ K. wanted to sit down, but then he saw that, apart from the chair by the window, there was nowhere anywhere in the room where he could sit. ‘You'll get the chance to see for yourself how true all this is,’ said Franz and both men then walked up to K. They were significantly bigger than him, especially the second man, who frequently slapped him on the shoulder. The two of them felt K.'s nightshirt, and said he would now have to wear one that was of much lower quality, but that they would keep the nightshirt along with his other underclothes and return them to him if his case turned out well.

. . . .

‘Allow me,’ [K] said, and hurried between the two policemen through into his room. ‘He seems sensible enough’, he heard them say behind him. Once in his room, he quickly pulled open the drawer of his writing desk, everything in it was very tidy but in his agitation he was unable to find the identification documents he was looking for straight away. He finally found his bicycle permit and was about to go back to the policemen with it when it seemed to him too petty, so he carried on searching until he found his birth certificate. Just as he got back in the adjoining room the door on the other side opened and Mrs. Grubach was about to enter. He only saw her for an instant, for as soon as she recognised K. she was clearly embarrassed, asked for forgiveness and disappeared, closing the door behind her very carefully. ‘Do come in,’ K. could have said just then. But now he stood in the middle of the room with his papers in his hand and still looking at the door which did not open again. He stayed like that until he was startled out of it by the shout of the policeman who sat at the little table at the open window and, as K. now saw, was eating his breakfast. ‘Why didn't she come in?’ he asked. ‘She's not allowed to,’ said the big policeman. ‘You're under arrest, aren't you.’ ‘But how can I be under arrest? And how come it's like this?’ ‘Now you're starting again,’ said the policeman, dipping a piece of buttered bread in the honeypot.

‘We don't answer questions like that.’ ‘You will have to answer them,’ said K. ‘Here are my identification papers, now show me yours and I certainly want to see the arrest warrant.’ ‘Oh, my God!' said the policeman. ‘In a position like yours, and you think you can start giving orders, do you? It won't do you any good to get us on the wrong side, even if you think it will — we’re probably more on your side that anyone else you know!’ ‘That's true, you know, you'd better believe it,' said Franz, holding a cup of coffee in his hand which he did not lift to his mouth but looked at K. in a way that was probably meant to be full of meaning but could not actually be understood.

— Frank Kafka, The Trial

Click on the white arrow to access the conversation:

The Abolition of Reality: A First Draft of the End of History, by John Waters, can now be ordered from Amazon and the website of the publishers, Western Frint Books.

These are the links for Amazon:

Amazon Ireland (Click just below):

Amazon UK (Click just below):

Amazon US (Click just below):

Amazon.com (United States, Canada, South America

Western Front Books:

The book can also be ordered from the publisher's website, where it can be purchased at a reduced price (this may take 1-2 weeks for delivery):